Watch a Wolf Cleverly Raid a Crab Trap for a Snack. It Might Be the First Evidence of a Wild Canid Using a Tool

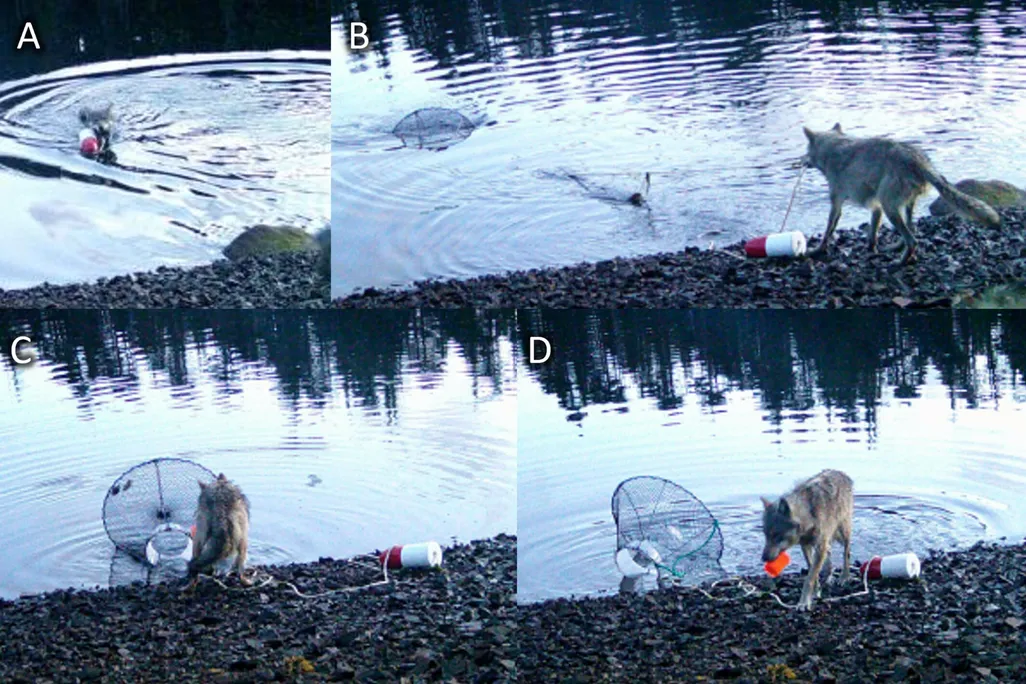

Watch a Wolf Cleverly Raid a Crab Trap for a Snack. It Might Be the First Evidence of a Wild Canid Using a Tool Footage from British Columbia shows just how intelligent wild wolves can be, but scientists are divided as to whether the behavior constitutes tool use Sarah Kuta - Daily Correspondent November 19, 2025 11:53 a.m. Members of the Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation caught the crafty female wolf on camera. Artelle et al. / Ecology and Evolution, 2025 Key takeaways: A dispute over tool use A female wolf figured out how to pull a crab trap from the ocean onto shore to fetch a tasty treat. Scientists debate whether the behavior represents tool use, or if the animal needed to have modified the object for it to count. Something strange began happening on the coast of British Columbia, Canada, in 2023. Traps set by members of the Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation to control invasive European green crabs kept getting damaged. Some had mangled bait cups or torn netting, but others were totally destroyed. But who—or what—was the culprit? Initially, the Indigenous community’s environmental wardens, called Guardians, suspected sea lions, seals or otters were to blame. But only after setting up several remote cameras in the area did they catch a glimpse of the true perpetrators: gray wolves. On May 29, 2024, one of the cameras recorded a female wolf emerging from the water with a buoy attached to a crab trap line in her mouth. Slowly but confidently, she tugged the line onto the beach until she’d managed to haul in the trap. Then, she tore open the bottom netting, removed the bait cup, had a snack and trotted off. Now, scientists say the incident—and another involving a different wolf in 2025—could represent the first evidence of tool use by wild wolves. They describe the behavior and lay out their conclusions in a new paper published November 17 in the journal Ecology and Evolution. This wolf has a unique way of finding food | Science News “You normally picture a human being with two hands pulling a crab trap,” says William Housty, a Haíɫzaqv hereditary chief and the director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, to Global News’ Amy Judd and Aaron McArthur. “But we couldn’t figure out exactly what had the ability to be able to do that until we put a camera up and saw, well, there’s other intelligent beings out there that are able to do this, which is very remarkable.” Members of the Haíɫzaqv Nation weren’t surprised by the wolves’ cleverness, as they have long considered the animals to be smart. That view has largely been shaped by the community’s oral history, which tells of a woman named C̓úṃqḷaqs who birthed four individuals who could shape-shift between humans and wolves, reports Science News’ Elie Dolgin. Scientists weren’t shocked, either, as they have long understood that wolves are intelligent, social creatures that often cooperate to take down their prey. People aren’t sure how the wolves figured out the crafty crab trap trick. The animals may have learned by watching Haíɫzaqv Guardians pull up the traps, or their keen sense of smell may have helped them sniff out the herring and sea lion bait inside. Or perhaps they started with traps that were more easily accessible, before moving on to more challenging targets submerged in deep water. Wolves are also largely protected in Haíɫzaqv territory, which may have given them the time and energy they needed to learn a new, complex behavior, reports the Washington Post’s Dino Grandoni. Whatever the explanation, experts are divided as to whether the behavior technically constitutes nonhuman tool use, which has been previously documented in crows, elephants, dolphins and several other species. The debate stems mostly from varying definitions of tool use. Under one definition, animals can’t simply use an external object to achieve a specific goal—the creature must also manipulate the object in some way, like a crow transforming a tree branch into a hooked tool for grabbing hidden insects. Against this backdrop, some researchers say the wolves’ behavior represents object use, not tool use. However, some of the disagreement may also be rooted in bias. “For better or for worse, as humans, we tend to afford more care and compassion to other people or other species that we see most like us,” says study co-author Kyle Artelle, an ecologist with the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, to the Washington Post. Marc Bekoff, a biologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved with the research, echoes that sentiment, telling Science’s Phie Jacobs that “if this had been a chimpanzee or other nonhuman primate, I’m sure no one would have blinked about whether this was tool use.” Regardless, scientists say the footage suggests wild wolves are even smarter than initially thought. In less than three minutes, the female efficiently and purposefully executed a complicated sequence of events to achieve a specific goal. She appeared to know that the trap contained food, even though it was hidden underwater, and she seemed to understand exactly which steps she needed to take to access that food. Tool use or not, the findings point to “another species with complex sociality [that] is capable of innovation and problem solving,” says Susana Carvalho, a primatologist and paleoanthropologist at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique who was not involved with the research, to the New York Times’ Lesley Evans Ogden. Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Footage from British Columbia shows just how intelligent wild wolves can be, but scientists are divided as to whether the behavior constitutes tool use

Watch a Wolf Cleverly Raid a Crab Trap for a Snack. It Might Be the First Evidence of a Wild Canid Using a Tool

Footage from British Columbia shows just how intelligent wild wolves can be, but scientists are divided as to whether the behavior constitutes tool use

Sarah Kuta - Daily Correspondent

Key takeaways: A dispute over tool use

- A female wolf figured out how to pull a crab trap from the ocean onto shore to fetch a tasty treat.

- Scientists debate whether the behavior represents tool use, or if the animal needed to have modified the object for it to count.

Something strange began happening on the coast of British Columbia, Canada, in 2023. Traps set by members of the Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation to control invasive European green crabs kept getting damaged. Some had mangled bait cups or torn netting, but others were totally destroyed.

But who—or what—was the culprit? Initially, the Indigenous community’s environmental wardens, called Guardians, suspected sea lions, seals or otters were to blame. But only after setting up several remote cameras in the area did they catch a glimpse of the true perpetrators: gray wolves.

On May 29, 2024, one of the cameras recorded a female wolf emerging from the water with a buoy attached to a crab trap line in her mouth. Slowly but confidently, she tugged the line onto the beach until she’d managed to haul in the trap. Then, she tore open the bottom netting, removed the bait cup, had a snack and trotted off.

Now, scientists say the incident—and another involving a different wolf in 2025—could represent the first evidence of tool use by wild wolves. They describe the behavior and lay out their conclusions in a new paper published November 17 in the journal Ecology and Evolution.

This wolf has a unique way of finding food | Science News

“You normally picture a human being with two hands pulling a crab trap,” says William Housty, a Haíɫzaqv hereditary chief and the director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, to Global News’ Amy Judd and Aaron McArthur. “But we couldn’t figure out exactly what had the ability to be able to do that until we put a camera up and saw, well, there’s other intelligent beings out there that are able to do this, which is very remarkable.”

Members of the Haíɫzaqv Nation weren’t surprised by the wolves’ cleverness, as they have long considered the animals to be smart. That view has largely been shaped by the community’s oral history, which tells of a woman named C̓úṃqḷaqs who birthed four individuals who could shape-shift between humans and wolves, reports Science News’ Elie Dolgin. Scientists weren’t shocked, either, as they have long understood that wolves are intelligent, social creatures that often cooperate to take down their prey.

People aren’t sure how the wolves figured out the crafty crab trap trick. The animals may have learned by watching Haíɫzaqv Guardians pull up the traps, or their keen sense of smell may have helped them sniff out the herring and sea lion bait inside. Or perhaps they started with traps that were more easily accessible, before moving on to more challenging targets submerged in deep water.

Wolves are also largely protected in Haíɫzaqv territory, which may have given them the time and energy they needed to learn a new, complex behavior, reports the Washington Post’s Dino Grandoni.

Whatever the explanation, experts are divided as to whether the behavior technically constitutes nonhuman tool use, which has been previously documented in crows, elephants, dolphins and several other species.

The debate stems mostly from varying definitions of tool use. Under one definition, animals can’t simply use an external object to achieve a specific goal—the creature must also manipulate the object in some way, like a crow transforming a tree branch into a hooked tool for grabbing hidden insects. Against this backdrop, some researchers say the wolves’ behavior represents object use, not tool use.

However, some of the disagreement may also be rooted in bias. “For better or for worse, as humans, we tend to afford more care and compassion to other people or other species that we see most like us,” says study co-author Kyle Artelle, an ecologist with the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, to the Washington Post.

Marc Bekoff, a biologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved with the research, echoes that sentiment, telling Science’s Phie Jacobs that “if this had been a chimpanzee or other nonhuman primate, I’m sure no one would have blinked about whether this was tool use.”

Regardless, scientists say the footage suggests wild wolves are even smarter than initially thought. In less than three minutes, the female efficiently and purposefully executed a complicated sequence of events to achieve a specific goal. She appeared to know that the trap contained food, even though it was hidden underwater, and she seemed to understand exactly which steps she needed to take to access that food.

Tool use or not, the findings point to “another species with complex sociality [that] is capable of innovation and problem solving,” says Susana Carvalho, a primatologist and paleoanthropologist at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique who was not involved with the research, to the New York Times’ Lesley Evans Ogden.