The Top Human Evolution Discoveries of 2025, From the Intriguing Neanderthal Diet to the Oldest Western European Face Fossil

The Top Human Evolution Discoveries of 2025, From the Intriguing Neanderthal Diet to the Oldest Western European Face Fossil Smithsonian paleoanthropologists examine the year’s most fascinating revelations Paranthropus boisei composite hand Courtesy of Carrie Mongle This has been quite the wild year in human evolution stories. Our relatives, living and extinct, got a lot of attention—from new developments in ape cognition to an expanded perspective of a big-toothed hominin cousin. A new view on a famous foot also revealed more about a lesser-known hominin species, Australopithecus deyiremeda. New tool and technology finds, coupled with dietary studies, showed us more than ever about the behavior of our ancestors and ourselves. New fossils gave us a glimpse at the earliest Europeans, predating both our own species and the Neanderthals. Finally, we dove deeper into the blockbuster story of the year, looking at some of the biggest Denisovan studies which give us a clearer than ever picture of these enigmatic human relatives.Human traits of chimps and bonobos Portrait of a bonobo Fiona Rogers / Getty Images A February study investigated theory of mind, or the uniquely human trait of recognizing the cognitive sapience of others, which allows modern humans to communicate and coordinate to an extent not seen in other animals. Study co-author Luke Townrow and colleagues set up an experiment where bonobos would receive a food reward hidden under cups, but only if they cooperated with their human partner and showed them where the food was first. Sometimes the bonobo could tell the human knew where the food was, and sometimes the animal could tell the human didn’t know where the food was. Bonobos pointed to the location of the hidden food more frequently and quicker when they knew the human was ignorant of the food’s location, indicating that they could interpret the human’s mental state and act accordingly, a hallmark of theory of mind. In addition to cooperating, an April study shows that apes also share, especially when it comes to fermented fruit. Anna Bowland and colleagues documented the first recorded instance of fermented food sharing in chimpanzees, observed in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea-Bissau. At least 17 chimps of all ages shared fermented breadfruits, ranging between 0.01 percent and 0.61 percent alcohol by volume. While this may not be enough ethanol to result in the sort of intoxication levels desired by many humans, this demonstrates that food sharing, and fermented food consumption, have deep evolutionary roots, supported by the evolution of ethanol metabolism among all African apes. On top of all that monkey business, an October study shows that chimps even have complex decision-making processes. Hanna Schleihauf and colleagues presented to chimps two boxes, one that contained food and one that was either empty or contained a non-food item. The chimps were allowed to choose a box twice, after receiving either weak or strong evidence about which box contains the food. The team found that chimps were able to revise their beliefs about the food’s location in response to more convincing evidence: When they picked the wrong box after the weak hint, they switched to the correct box after the following strong hint. Also, when they picked the correct box after a strong hint, they kept their selection after a weak hint. The study highlights the chimpanzees’ ability to make rational decisions, and even change decisions, in response to learning new information. Fun fact: Chimps may use medicinal herbs In a study last year, researchers collected extracts of plants that they saw chimpanzees eating outside of their normal diets in Uganda’s Budongo Central Forest Reserve. The researchers discovered that “88 percent of the plant extracts inhibited bacterial growth, while 33 percent had anti-inflammatory properties.” A holistic picture of Paranthropus The reconstructed left hand of the Paranthropus boisei Mongle, Carrie et al., Nature, 2025 Besides learning more about our ape relatives, we also learned a lot more about some of our hominin cousins this year. Paranthropus is a genus of hominins consisting of three species, mostly known for their large teeth and massive chewing muscles that they likely used to break down tough plant fibers. However, not much was known about them outside of their mouths and skulls. A Paranthropus study from April helps to close this gap, describing an articulated lower limb from the Swartkrans site in South Africa. Travis Pickering and colleagues described a partial pelvis, femur and tibia of an adult Paranthropus robustus dating back 2.3 million to 1.7 million years ago. The anatomy of the hip, femur and knee indicate that this individual was fully bipedal. This hominin would probably have been only about three feet tall, one of the tiniest hominins on record. Due to a lack of other fossil material for comparison and the pelvis fossil being very incomplete, estimating the sex of this individual is more difficult. However, another study from May pioneered the use of different methods to estimate the sex of Paranthropus fossils. Analyzing proteins preserved in fossil tooth enamel, Palesa Madupe and colleagues were able to determine sex and begin to investigate genetic variability in Paranthropus fossils from South Africa. Using these proteins, the team was able to identify two male and two female individuals, allowing for more accurate hypotheses about sexual dimorphism (sex-based body size and shape differences). The team also found that one of the individuals appeared to be more distantly related, hinting at microevolution within this species. Lastly, a study published in October described a Paranthropus boisei hand from the Koobi Fora site in Kenya, which allowed scientists to learn if Paranthropus could have made stone tools. Carrie Mongle and colleagues looked at the nearly complete Paranthropus hand, which reveals a mostly hominin-looking morphology. Yet with strong musculature and wide bones, the grasping capabilities of Paranthropus seem to converge with that of gorillas, although they likely used this powerful grip to strip vegetation and process food rather than for climbing. Additionally, with a long thumb and precision grasping capabilities, the authors hypothesize that nothing in their hand morphology would have prevented Paranthropus boisei from making and using stone tools. This builds on other recent finds suggesting that the ability to make and use complex tools was not limited to the genus Homo.The family of a famous footThe Burtele foot, a fossil from Ethiopia that was described in 2012 and originally not given a species designation, dates to about 3.4 million years ago. Despite being contemporaneous with Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy’s species, the fossil looked almost nothing like it. The locomotor adaptations were completely different, and the foot still had an opposable big toe, like modern apes and the earlier genus Ardipithecus. In November, Yohannes Haile-Selassie and colleagues published research on other fossils from the same site where the Burtele foot was found. A new mandible with teeth links the hominin fossils at Burtele to a less well-known species, Australopithecus deyiremeda. This species had primitive teeth and grasping feet, with isotopic evidence pointing to a plant-based diet more similar to that of earlier species like Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus anamensis. These new finds show that primitive traits persisted more recently into the timeline of human evolution and that our family tree is even bushier than previously thought.Ancient tool technologies An ancient ochre fragment that shows signs of re-use d’Errico, Francesco et al., Science Advances, 2025 Archaeological sites, by definition, are evidence of past human behavior. But it’s not often a find is unearthed that turns out to be evidence of just one past human’s behavior. A study in August by Dominik Chlachula and colleagues reports on a small cluster of 29 stone artifacts from the Milovice IV site in the Czech Republic that were probably bundled together in a container or pouch made of perishable material: basically, a Stone Age hunter-gatherer’s personal toolkit. The 30,000-year-old blade and bladelet tools were made from different kinds of stone (flint, radiolarite, chert and opal). Use-wear analysis showed they were used for cutting, scraping and drilling, and the kit also included projectiles used for hunting. Now we move farther back in time, to when some of the earliest members of our lineage were making tools. In November, David Braun and colleagues reported on stone toolmaking in the Turkana Basin of Kenya that started about 2.75 million years ago at the new site of Namorotukunan, which contains one of the oldest and longest intervals of the making of Oldowan tools. This simple core-and-flake technology was, as revealed by this new evidence, nevertheless undertaken with enough skill—and the tools useful enough for various activities—to be made consistently for almost 300,000 years, through dramatic environmental changes, highlighting our ancestors’ resilience. However, not all ancient tools were made for practical purposes. In October, Francesco d’Errico and colleagues described three pieces of ochre, an iron-rich mineral pigment, from archaeological sites in Crimea, Ukraine. These artifacts were deliberately collected, shaped, engraved, polished, resharpened and deposited there by Neanderthals up to 70,000 years ago. Although it’s impossible to know what the Neanderthals did with these yellow and red pigments, the fact that they seemed to be kept sharpened suggests that their tips were used to produce linear marks. This suggests that they had a symbolic or artistic function, rather than a utilitarian one, perhaps playing a role in identity expression, communication and transmitting knowledge across generations.Neanderthal eating habitsWhen they weren’t busy coloring with paleo-crayons, our Neanderthal cousins are known for being skilled hunters of large animals, and two studies in July shed new light on their diets. First, Lutz Kindler and colleagues documented that 125,000 years ago, at the site of Neumark-Nord in Germany, Neanderthals processed at least 172 animals at the edge of a lake, most likely to extract bone grease. This “fat factory,” as the researchers called it, is much older than previously documented grease extraction sites, and this extreme bone-bashing behavior had not been seen before at Neanderthal sites. The team documented how Neanderthals transported the bones of these animals, mostly antelope, deer and horses, but even some forest elephants, to the site to crush, chop up and boil to get at the nutritious, calorie-rich fat inside. (Speaking of Neanderthals cooking things, a December study by Rob Davis, Nick Ashton and colleagues documented the earliest evidence of deliberate fire-making from the 400,000-year-old site of Barnham in England, where they found heated sediments, fire-cracked flint handaxes and fragments of iron pyrite—a mineral used to strike sparks with flint—likely brought to the site from far away.) Later in July, Melanie Beasley and colleagues made an intriguing suggestion about the Neanderthal diet. Humans and our earlier relatives can only eat a certain proportion of protein in our diets without getting protein poisoning, but chemical signatures (specifically, nitrogen isotope values) in Neanderthal bones indicate that they ate as much protein as other ancient hyper-carnivores. So, what was causing this? Maybe it was maggots, fat-rich fly larvae. When an animal dies, maggots feed on the decaying flesh, which has higher nitrogen values as it decomposes. Many Indigenous forager groups regard putrid meat as a tasty treat. If Neanderthals were eating nitrogen-enriched maggots feeding on rotting muscle tissue in dried, frozen or cached (deliberately stored) dead animals, that might at least partly explain their unusually high nitrogen values. While our later evolutionary cousins may have munched on maggots, a study in January by Tina Lüdecke and colleagues looked at carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the teeth of Australopithecus and other animal species dating back more than three million years ago from South Africa’s Sterkfontein site. The isotope ratios of the seven Australopithecus teeth were variable but consistently low, and more similar to the contemporaneous herbivores than the carnivores, suggesting they were not consuming much meat. This follows with other recent studies suggesting, contrary to common belief, that carnivory was not a major factor shaping our evolution.The earliest EuropeansTwo studies this year focused on early evidence for hominins in Europe. In January, Sabrina Curran and colleagues reported cut marks on several animal bones from the Graunceanu site in Romania, dating to at least 1.95 million years ago—now among the earliest evidence that hominins had spread to Eurasia by that time. To verify that these were cut marks made by stone tools, they compared 3D shape data from impressions of the marks to a reference set of almost 900 modern marks made by stone tool butchery, carnivore feeding and sedimentary abrasion. They concluded that the marks on eight Graunceanu fossils, mainly hoofed animals like deer, were stone tool cut marks. In March, Rosa Huguet and colleagues reported on the earliest hominin face fossil from Western Europe, dated to 1.4 million-1.1 million years ago, found in Spain. The shape of the left half of the face fossil is more similar to Homo erectus (which had not been documented in Europe), rather than resembling later and more modern looking Homo antecessor fossils found almost 1,000 feet away and dated to between 900,000-800,000 years ago. The scientific name of the new fossil is ATE7-1, but its nickname is “Pink.” This is a nod to Pink Floyd’s album The Dark Side of the Moon, which in Spanish is La cara oculta de la luna (cara oculta means hidden face). Also, Huguet’s first name, Rosa, is Spanish for pink.New Denisovan discoveries A reconstruction of the Harbin cranium by paleoartist John Gurche Courtesy of John Gurche Denisovan fossils have been found in Siberia and throughout East Asia, although they are few and far between. Denisovans may be our most enigmatic cousins, because we’ve learned more about them through DNA, including DNA we got from interbreeding with them, than from their fossils. Until this year, that is. A study from April described a new Denisovan mandible. Takumi Tsutaya and colleagues analyzed the Penghu 1 mandible, dredged up from the coast of Taiwan, and discovered that the morphology and protein sequences both matched it with Denisovans. Proteomics also allowed the team to determine this was a male individual, and this find expands the known range of Denisovans into warmer, wetter regions of Asia. Next, two stories from this summer took a second look at the Harbin cranium, termed “Dragon Man” and given the species name Homo longi in 2021. The first study, in June, looked at the proteome of the Harbin cranium, while the second study, in July, looked at the mitochondrial DNA; both studies were led by Qiaomei Fu. While no DNA was able to be retrieved from the fossil itself, proteomics and the DNA from dental calculus both suggested that this fossil was part of the Denisovan group. Together, these studies give the first look at the face of a Denisovan, lining up morphology with molecules. While more work needs to be done to build the body of evidence and give scientists a more complete view of Denisovan anatomy, habitat and behavior, being able to link complete fossils with the molecular evidence is a huge step forward. While it is unclear what this means for the name “Denisovan” itself, we hypothesize that it will persist as a popular or common name, much like how we call Homo neanderthalensis “Neanderthals” today. Lastly, in September, Xiaobo Feng and colleagues reconstructed and described the Yunxian 2 cranium from China, dating to one million years ago. The skull was meticulously reconstructed from crushed and warped fragments and appears to have a mix of primitive and derived traits, and it is also closely aligned with the Homo longi group. The phylogenetic analysis conducted by the team changes the perspective of late hominin divergence, with Homo longi and Homo sapiens being sister taxa to the exclusion of Neanderthals, and all three groups having evolutionary origins two to three times older than previously thought: at least 1.2 million years ago. While more finds will support or refute these phylogenetic claims, new fossil evidence continues to help refine our understanding of our lineage—and never stops surprising us.This story originally appeared in PLOS SciComm, a blog from PLOS, a nonprofit that publishes open-access scientific studies. Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

Smithsonian paleoanthropologists examine the year’s most fascinating revelations

The Top Human Evolution Discoveries of 2025, From the Intriguing Neanderthal Diet to the Oldest Western European Face Fossil

Smithsonian paleoanthropologists examine the year’s most fascinating revelations

This has been quite the wild year in human evolution stories. Our relatives, living and extinct, got a lot of attention—from new developments in ape cognition to an expanded perspective of a big-toothed hominin cousin. A new view on a famous foot also revealed more about a lesser-known hominin species, Australopithecus deyiremeda. New tool and technology finds, coupled with dietary studies, showed us more than ever about the behavior of our ancestors and ourselves. New fossils gave us a glimpse at the earliest Europeans, predating both our own species and the Neanderthals. Finally, we dove deeper into the blockbuster story of the year, looking at some of the biggest Denisovan studies which give us a clearer than ever picture of these enigmatic human relatives.

Human traits of chimps and bonobos

A February study investigated theory of mind, or the uniquely human trait of recognizing the cognitive sapience of others, which allows modern humans to communicate and coordinate to an extent not seen in other animals. Study co-author Luke Townrow and colleagues set up an experiment where bonobos would receive a food reward hidden under cups, but only if they cooperated with their human partner and showed them where the food was first. Sometimes the bonobo could tell the human knew where the food was, and sometimes the animal could tell the human didn’t know where the food was. Bonobos pointed to the location of the hidden food more frequently and quicker when they knew the human was ignorant of the food’s location, indicating that they could interpret the human’s mental state and act accordingly, a hallmark of theory of mind.

In addition to cooperating, an April study shows that apes also share, especially when it comes to fermented fruit. Anna Bowland and colleagues documented the first recorded instance of fermented food sharing in chimpanzees, observed in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea-Bissau. At least 17 chimps of all ages shared fermented breadfruits, ranging between 0.01 percent and 0.61 percent alcohol by volume. While this may not be enough ethanol to result in the sort of intoxication levels desired by many humans, this demonstrates that food sharing, and fermented food consumption, have deep evolutionary roots, supported by the evolution of ethanol metabolism among all African apes.

On top of all that monkey business, an October study shows that chimps even have complex decision-making processes. Hanna Schleihauf and colleagues presented to chimps two boxes, one that contained food and one that was either empty or contained a non-food item. The chimps were allowed to choose a box twice, after receiving either weak or strong evidence about which box contains the food. The team found that chimps were able to revise their beliefs about the food’s location in response to more convincing evidence: When they picked the wrong box after the weak hint, they switched to the correct box after the following strong hint. Also, when they picked the correct box after a strong hint, they kept their selection after a weak hint. The study highlights the chimpanzees’ ability to make rational decisions, and even change decisions, in response to learning new information.

Fun fact: Chimps may use medicinal herbs

- In a study last year, researchers collected extracts of plants that they saw chimpanzees eating outside of their normal diets in Uganda’s Budongo Central Forest Reserve.

- The researchers discovered that “88 percent of the plant extracts inhibited bacterial growth, while 33 percent had anti-inflammatory properties.”

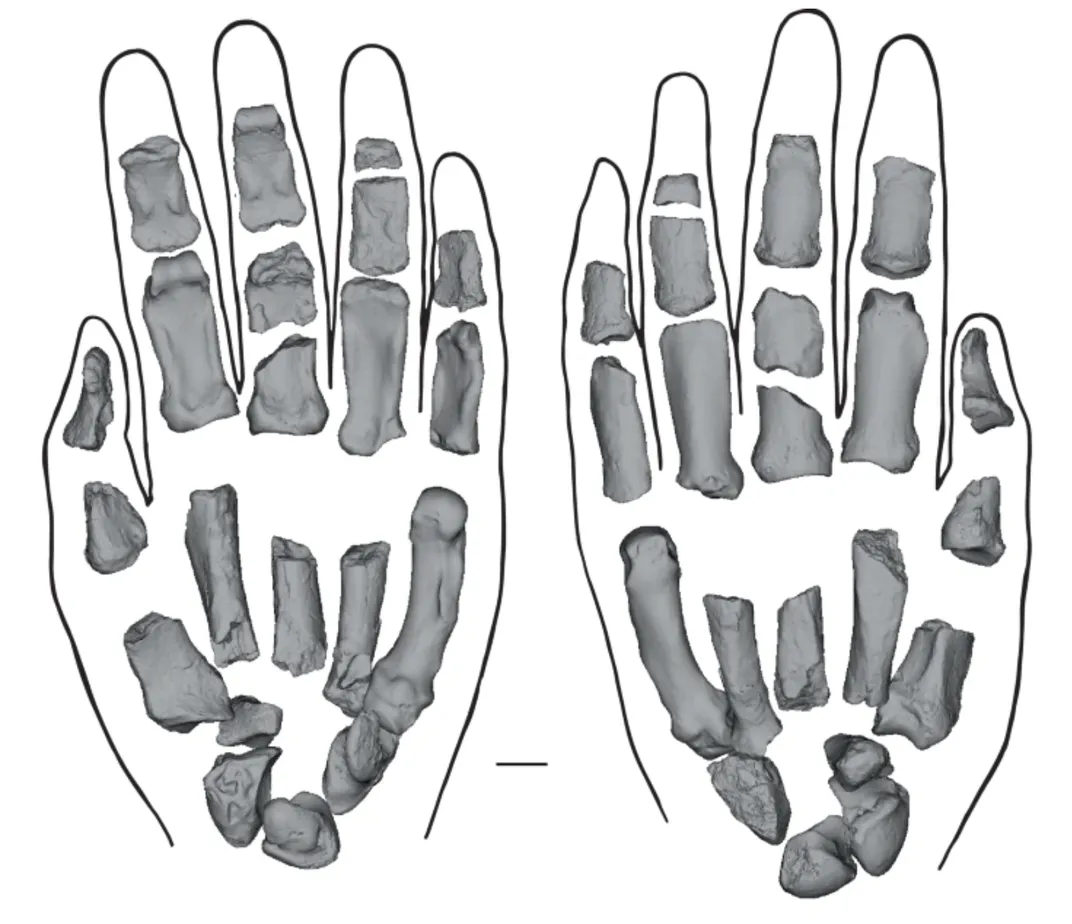

A holistic picture of Paranthropus

Besides learning more about our ape relatives, we also learned a lot more about some of our hominin cousins this year. Paranthropus is a genus of hominins consisting of three species, mostly known for their large teeth and massive chewing muscles that they likely used to break down tough plant fibers. However, not much was known about them outside of their mouths and skulls. A Paranthropus study from April helps to close this gap, describing an articulated lower limb from the Swartkrans site in South Africa. Travis Pickering and colleagues described a partial pelvis, femur and tibia of an adult Paranthropus robustus dating back 2.3 million to 1.7 million years ago. The anatomy of the hip, femur and knee indicate that this individual was fully bipedal. This hominin would probably have been only about three feet tall, one of the tiniest hominins on record. Due to a lack of other fossil material for comparison and the pelvis fossil being very incomplete, estimating the sex of this individual is more difficult.

However, another study from May pioneered the use of different methods to estimate the sex of Paranthropus fossils. Analyzing proteins preserved in fossil tooth enamel, Palesa Madupe and colleagues were able to determine sex and begin to investigate genetic variability in Paranthropus fossils from South Africa. Using these proteins, the team was able to identify two male and two female individuals, allowing for more accurate hypotheses about sexual dimorphism (sex-based body size and shape differences). The team also found that one of the individuals appeared to be more distantly related, hinting at microevolution within this species.

Lastly, a study published in October described a Paranthropus boisei hand from the Koobi Fora site in Kenya, which allowed scientists to learn if Paranthropus could have made stone tools. Carrie Mongle and colleagues looked at the nearly complete Paranthropus hand, which reveals a mostly hominin-looking morphology. Yet with strong musculature and wide bones, the grasping capabilities of Paranthropus seem to converge with that of gorillas, although they likely used this powerful grip to strip vegetation and process food rather than for climbing. Additionally, with a long thumb and precision grasping capabilities, the authors hypothesize that nothing in their hand morphology would have prevented Paranthropus boisei from making and using stone tools. This builds on other recent finds suggesting that the ability to make and use complex tools was not limited to the genus Homo.

The family of a famous foot

The Burtele foot, a fossil from Ethiopia that was described in 2012 and originally not given a species designation, dates to about 3.4 million years ago. Despite being contemporaneous with Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy’s species, the fossil looked almost nothing like it. The locomotor adaptations were completely different, and the foot still had an opposable big toe, like modern apes and the earlier genus Ardipithecus. In November, Yohannes Haile-Selassie and colleagues published research on other fossils from the same site where the Burtele foot was found. A new mandible with teeth links the hominin fossils at Burtele to a less well-known species, Australopithecus deyiremeda. This species had primitive teeth and grasping feet, with isotopic evidence pointing to a plant-based diet more similar to that of earlier species like Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus anamensis. These new finds show that primitive traits persisted more recently into the timeline of human evolution and that our family tree is even bushier than previously thought.

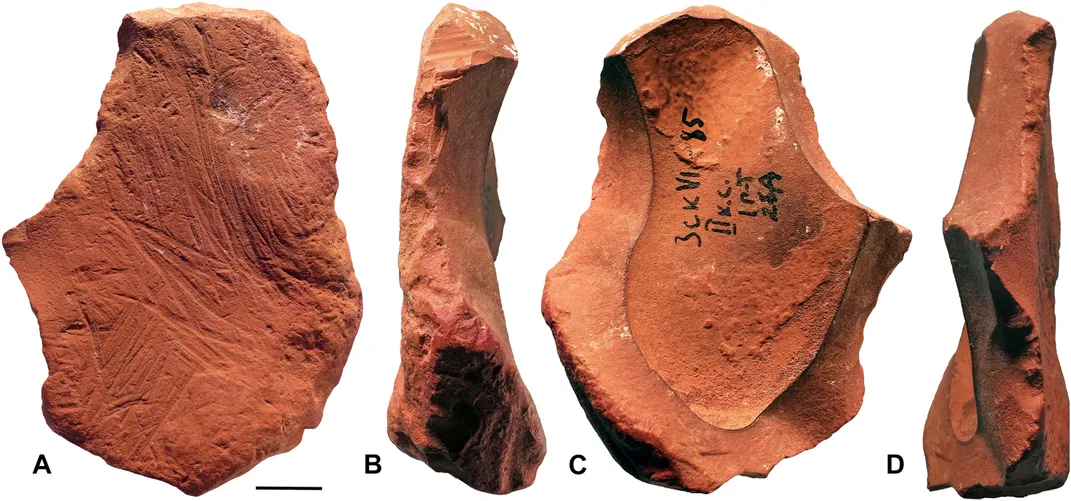

Ancient tool technologies

Archaeological sites, by definition, are evidence of past human behavior. But it’s not often a find is unearthed that turns out to be evidence of just one past human’s behavior. A study in August by Dominik Chlachula and colleagues reports on a small cluster of 29 stone artifacts from the Milovice IV site in the Czech Republic that were probably bundled together in a container or pouch made of perishable material: basically, a Stone Age hunter-gatherer’s personal toolkit. The 30,000-year-old blade and bladelet tools were made from different kinds of stone (flint, radiolarite, chert and opal). Use-wear analysis showed they were used for cutting, scraping and drilling, and the kit also included projectiles used for hunting.

Now we move farther back in time, to when some of the earliest members of our lineage were making tools. In November, David Braun and colleagues reported on stone toolmaking in the Turkana Basin of Kenya that started about 2.75 million years ago at the new site of Namorotukunan, which contains one of the oldest and longest intervals of the making of Oldowan tools. This simple core-and-flake technology was, as revealed by this new evidence, nevertheless undertaken with enough skill—and the tools useful enough for various activities—to be made consistently for almost 300,000 years, through dramatic environmental changes, highlighting our ancestors’ resilience.

However, not all ancient tools were made for practical purposes. In October, Francesco d’Errico and colleagues described three pieces of ochre, an iron-rich mineral pigment, from archaeological sites in Crimea, Ukraine. These artifacts were deliberately collected, shaped, engraved, polished, resharpened and deposited there by Neanderthals up to 70,000 years ago. Although it’s impossible to know what the Neanderthals did with these yellow and red pigments, the fact that they seemed to be kept sharpened suggests that their tips were used to produce linear marks. This suggests that they had a symbolic or artistic function, rather than a utilitarian one, perhaps playing a role in identity expression, communication and transmitting knowledge across generations.

Neanderthal eating habits

When they weren’t busy coloring with paleo-crayons, our Neanderthal cousins are known for being skilled hunters of large animals, and two studies in July shed new light on their diets. First, Lutz Kindler and colleagues documented that 125,000 years ago, at the site of Neumark-Nord in Germany, Neanderthals processed at least 172 animals at the edge of a lake, most likely to extract bone grease. This “fat factory,” as the researchers called it, is much older than previously documented grease extraction sites, and this extreme bone-bashing behavior had not been seen before at Neanderthal sites. The team documented how Neanderthals transported the bones of these animals, mostly antelope, deer and horses, but even some forest elephants, to the site to crush, chop up and boil to get at the nutritious, calorie-rich fat inside. (Speaking of Neanderthals cooking things, a December study by Rob Davis, Nick Ashton and colleagues documented the earliest evidence of deliberate fire-making from the 400,000-year-old site of Barnham in England, where they found heated sediments, fire-cracked flint handaxes and fragments of iron pyrite—a mineral used to strike sparks with flint—likely brought to the site from far away.)

Later in July, Melanie Beasley and colleagues made an intriguing suggestion about the Neanderthal diet. Humans and our earlier relatives can only eat a certain proportion of protein in our diets without getting protein poisoning, but chemical signatures (specifically, nitrogen isotope values) in Neanderthal bones indicate that they ate as much protein as other ancient hyper-carnivores. So, what was causing this? Maybe it was maggots, fat-rich fly larvae. When an animal dies, maggots feed on the decaying flesh, which has higher nitrogen values as it decomposes. Many Indigenous forager groups regard putrid meat as a tasty treat. If Neanderthals were eating nitrogen-enriched maggots feeding on rotting muscle tissue in dried, frozen or cached (deliberately stored) dead animals, that might at least partly explain their unusually high nitrogen values.

While our later evolutionary cousins may have munched on maggots, a study in January by Tina Lüdecke and colleagues looked at carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the teeth of Australopithecus and other animal species dating back more than three million years ago from South Africa’s Sterkfontein site. The isotope ratios of the seven Australopithecus teeth were variable but consistently low, and more similar to the contemporaneous herbivores than the carnivores, suggesting they were not consuming much meat. This follows with other recent studies suggesting, contrary to common belief, that carnivory was not a major factor shaping our evolution.

The earliest Europeans

Two studies this year focused on early evidence for hominins in Europe. In January, Sabrina Curran and colleagues reported cut marks on several animal bones from the Graunceanu site in Romania, dating to at least 1.95 million years ago—now among the earliest evidence that hominins had spread to Eurasia by that time. To verify that these were cut marks made by stone tools, they compared 3D shape data from impressions of the marks to a reference set of almost 900 modern marks made by stone tool butchery, carnivore feeding and sedimentary abrasion. They concluded that the marks on eight Graunceanu fossils, mainly hoofed animals like deer, were stone tool cut marks.

In March, Rosa Huguet and colleagues reported on the earliest hominin face fossil from Western Europe, dated to 1.4 million-1.1 million years ago, found in Spain. The shape of the left half of the face fossil is more similar to Homo erectus (which had not been documented in Europe), rather than resembling later and more modern looking Homo antecessor fossils found almost 1,000 feet away and dated to between 900,000-800,000 years ago. The scientific name of the new fossil is ATE7-1, but its nickname is “Pink.” This is a nod to Pink Floyd’s album The Dark Side of the Moon, which in Spanish is La cara oculta de la luna (cara oculta means hidden face). Also, Huguet’s first name, Rosa, is Spanish for pink.

New Denisovan discoveries

Denisovan fossils have been found in Siberia and throughout East Asia, although they are few and far between. Denisovans may be our most enigmatic cousins, because we’ve learned more about them through DNA, including DNA we got from interbreeding with them, than from their fossils. Until this year, that is. A study from April described a new Denisovan mandible. Takumi Tsutaya and colleagues analyzed the Penghu 1 mandible, dredged up from the coast of Taiwan, and discovered that the morphology and protein sequences both matched it with Denisovans. Proteomics also allowed the team to determine this was a male individual, and this find expands the known range of Denisovans into warmer, wetter regions of Asia.

Next, two stories from this summer took a second look at the Harbin cranium, termed “Dragon Man” and given the species name Homo longi in 2021. The first study, in June, looked at the proteome of the Harbin cranium, while the second study, in July, looked at the mitochondrial DNA; both studies were led by Qiaomei Fu. While no DNA was able to be retrieved from the fossil itself, proteomics and the DNA from dental calculus both suggested that this fossil was part of the Denisovan group. Together, these studies give the first look at the face of a Denisovan, lining up morphology with molecules. While more work needs to be done to build the body of evidence and give scientists a more complete view of Denisovan anatomy, habitat and behavior, being able to link complete fossils with the molecular evidence is a huge step forward. While it is unclear what this means for the name “Denisovan” itself, we hypothesize that it will persist as a popular or common name, much like how we call Homo neanderthalensis “Neanderthals” today.

Lastly, in September, Xiaobo Feng and colleagues reconstructed and described the Yunxian 2 cranium from China, dating to one million years ago. The skull was meticulously reconstructed from crushed and warped fragments and appears to have a mix of primitive and derived traits, and it is also closely aligned with the Homo longi group. The phylogenetic analysis conducted by the team changes the perspective of late hominin divergence, with Homo longi and Homo sapiens being sister taxa to the exclusion of Neanderthals, and all three groups having evolutionary origins two to three times older than previously thought: at least 1.2 million years ago.

While more finds will support or refute these phylogenetic claims, new fossil evidence continues to help refine our understanding of our lineage—and never stops surprising us.

This story originally appeared in PLOS SciComm, a blog from PLOS, a nonprofit that publishes open-access scientific studies.