The used oil from your french fry order may be fueling your next flight

Le Diplomate had an emergency. After a week of frying frites, the kitchen at Washington’s famous standby for French cuisine was full to bursting with used grease.Two waist-high storage tanks in the back of the restaurant sloshed to the brim with dark, viscous oil. During the weekend rush, the staff stored some of the spent grease in plastic tubs, but they were quickly running out of places to put it.Restaurants are prohibited from dumping grease down the drain because it would clog city sewers. So on a Tuesday afternoon, James Howell nimbly backed his truck into an alley behind Le Diplomate. He hopped down from the cab and snaked a rubber hose to the kitchen. Then with the flip of a switch and a loud drone, the hose slurped the used cooking oil into the truck’s gleaming steel 2,200-gallon tank.James Howell of Mahoney Environmental collects used cooking oil behind Duke’s Grocery in Washington. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)Three bottles — with raw oil on the left, half-processed produce in the middle and refined aviation fuel on the right — in the Neste laboratory in Rotterdam. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/For The Washington Post)The spent grease that restaurants unload as waste has become a valuable commodity. If you’ve been on a plane lately, there’s a chance that used cooking oil has helped launch you into the sky. Refineries recycle waste oil into kerosene pure enough to power a Boeing 777. The process is expensive — but it can create 70 to 80 percent less planet-warming pollution than making jet fuel out of crude oil, experts say.Last year, airlines burned 340 million gallons of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) — nearly all of it made from used cooking oil or animal fat leftover from meat packaging.A series examining innovative and impactful approaches to addressing waste.That’s a drop in the bucket compared to the 114 billion gallons of fuel airlines burned overall, which create 2.5 percent of humanity’s carbon pollution, according to the International Energy Agency. But airlines have vowed to use much more SAF to lower their greenhouse emissions. European regulators have set strict rules requiring airlines to use more SAF over time, while U.S. regulators dole out tax credits to coax companies into buying it.This is the airlines’ main plan for dealing with their greenhouse emissions. Upgrading new planes with more efficient engines helps a little. And, one day, planes may run on electric batteries or hydrogen fuel cells — but those are still decades away and may never work for long flights. To manage most of their climate impact for the foreseeable future, airlines are betting everything on alternative fuels.“Ninety-eight percent of [our greenhouse emissions] come from the fuel we burn,” said Lauren Riley, chief sustainability officer at United Airlines. “We’ll continue to look everywhere we can around technology and innovation of the aircraft itself and the engine, but we have to look at replacing our fuel.”Experts say this plan can work, but it’ll require fuel refiners to dramatically raise SAF production and find new raw materials besides old cooking oil to turn into kerosene. Depending on what they use and how they refine it, this new class of fuel could make flying more sustainable or cause a whole new set of environmental headaches.Howell, of Mahoney Environmental, collects used cooking oil in Washington. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)Harvesting the world’s greaseOn his rounds one day in early May, Howell made about two dozen stops at commercial kitchens around Washington, including an upscale cafe in the Michelin Guide, an assisted-living facility, a soul food spot where old chicken bones clogged the hose and an Italian restaurant where two unfortunate rats had drowned in a grease bin while diving for a wayward meatball. By midafternoon, his truck had about 1,200 gallons of grease in its belly.The company he works for, Mahoney Environmental, pays a few cents a gallon for the waste fat it collects from 90,000 businesses in the United States. Hundreds of companies gather grease around the globe — with an especially large haul in Southeast Asia, where densely packed restaurants serve up so much fried food that they’ve become the waste oil equivalent of Saudi Arabia’s rich petroleum fields.Waste oil from kitchens and animal tallow leftover from meatpacking plants used to be recycled into livestock feed. But now, they are mostly turned into fuel: Fat molecules hold a lot of energy, and they’re relatively easy to rearrange into diesel and kerosene.Turning fat into fuel keeps grease out of the landfill and petroleum in the ground. The demand, though, has begun to outstrip the supply.“There’s only so many waste oils to go around, and … you can’t really squeeze out much more,” said Nikita Pavlenko, who leads the aviation and fuels team at the nonprofit International Council on Clean Transportation. “People aren’t going to be frying more food or processing more cattle to get waste tallow to make fuel. You’re kind of stuck with what you have.”A hose is deployed to suck used cooking oil into the tank of a collection truck. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)Storage tanks for the feedstock (oil or tallow) at Neste in Rotterdam. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/For The Washington Post)As regulators push companies to buy and make more fuel from fat, the price of grease has been rising, along with the crime surrounding it.Thieves sometimes steal grease from collection bins and sell it themselves. Once, Howell said, he stopped at a restaurant only to find an empty bin and a confused cook, who told him an unmarked van had come by earlier and siphoned off their oil.Grease fraud is a problem, too. In some areas, used cooking oil sells for more than new cooking oil, prompting hucksters to sell virgin oil — including palm oil, which is associated with deforestation in Southeast Asia — as if it were used. It’s hard to catch, since fresh oil spiked with a little restaurant grease is almost indistinguishable from the real thing.“You’re potentially paying a premium for something that is worse than fossil fuel,” Pavlenko said.Fuel companies crack down on fraud by hiring inspectors to go out and check that their grease suppliers really are pumping their product out of deep fat fryers. On his route, Howell takes pictures of every bin before and after he drains it and uploads the proof to a Mahoney Environmental app that verifies where his oil came from.At the end of the day, Howell unloads his truck at a depot, where the oil is filtered to remove water, flour, spices and any other floating food chunks.Lab shift supervisor Jeroen van der Heijden in the laboratory at Neste. Neste produces sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), with a key presence in the Netherlands at its Rotterdam refinery. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/For The Washington Post)Turning fat into fuelUsed grease is a global commodity. Once it’s collected, tanker ships and pipelines carry it to fuel refineries around the world — much like they do for crude oil.Grease ships arrive a couple of times a week at a refinery in Rotterdam run by Neste, the world’s top producer of sustainable jet fuel.How grease is turned into jet fuelThe Neste facility, located in Europe’s largest port, is ramping up production of SAF made from used cooking oil. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/For The Washington Post)Fueling the appetite for sustainable fuelIn 2023, a Boeing 777 flew across the Atlantic Ocean burning fuel made from nothing but waste fat and sugar. The flight was a first, but it was really a publicity stunt — carrying Virgin Atlantic bigwigs, not paying passengers. The fuel is too expensive, and too scarce, for that to make business sense.Instead, Neste blends its french fry fuel with standard kerosene made from crude oil before delivering it to airports.SAF is almost identical to standard jet fuel, and it releases just as much CO2 when it’s burned. But experts say there’s a key difference: Drilling for oil takes carbon that was locked away underground and releases it into the atmosphere. Making fuel from used cooking oil and tallow takes carbon that was already circulating through the air and the bodies of plants and animals and recycles it. No new carbon moves from underground storage into the atmosphere.Sample vials at Neste. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/For The Washington Post)Site director Hanna van Luijk at Neste. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/For The Washington Post)It takes energy to collect and transport used cooking oil, rearrange fat molecules into jet fuel and get that fuel to planes. But, overall, making and burning SAF adds as much as 80 percent less carbon to the atmosphere as making and burning fossil fuel from crude oil.Because there isn’t enough waste oil in the world to satisfy the airline industry’s thirst, companies are developing other ways to make low-carbon jet fuel. One option is to grow more crops like soy that can be crushed for oil and turned into jet fuel — although that raises the risk that more land will be cleared for farming in fragile ecosystems like the Brazilian Amazon. Environmentalists have raised similar concerns about raising more corn, sugar cane or beets to create ethanol and convert it into kerosene.“The problem with crop-based biofuels is it takes land to produce them at a time when we’re already expanding cropland … which means more deforestation, and the carbon losses are far greater than the potential savings from reducing fossil fuel use,” said Tim Searchinger, a senior research scholar at Princeton’s Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment.Alternately, farmers could grow more cover crops on their fields between their regular planting seasons, which would create a new source of plant oils or ethanol without using extra land. Some companies have experimented with turning trash into jet fuel, but the most prominent player went bankrupt last year. Others are splitting water molecules to harvest their hydrogen and combining it with captured carbon to make fuel.Experts say it will take a combination of all these methods to make enough green fuel to power the world’s planes.Howell, of Mahoney Environmental, collects used cooking oil behind Umai Nori. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)The one thing every alternative fuel recipe has in common is that they are more expensive than fossil fuel — and experts say they always will be. Making SAF from waste oil is “locked in at a cost which is about two times the cost of fossil jet, and it’s going to be entirely reliant on subsidies,” according to Pavlenko. The other methods could be even more expensive, even after they’ve had time to raise production and lower costs.The future of the industry will depend on whether the United States keeps tax credits in place and the European Union stands by its green fuel mandates. Neste is expanding its Rotterdam refinery in anticipation of stricter E.U. blending rules, and in the United States, the first large-scale SAF operations started pumping out fuel in recent years in response to new tax credits that have since been weakened.Back at Le Diplomate, amid the evening dinner rush, frites flow out of the kitchen to feed hungry diners who are unwittingly helping launch planes into the sky with every bite.

We followed the trail of grease from the kitchens of Le Diplomat and other D.C. restaurants to the commercial planes using alternative fuels.

Le Diplomate had an emergency. After a week of frying frites, the kitchen at Washington’s famous standby for French cuisine was full to bursting with used grease.

Two waist-high storage tanks in the back of the restaurant sloshed to the brim with dark, viscous oil. During the weekend rush, the staff stored some of the spent grease in plastic tubs, but they were quickly running out of places to put it.

Restaurants are prohibited from dumping grease down the drain because it would clog city sewers. So on a Tuesday afternoon, James Howell nimbly backed his truck into an alley behind Le Diplomate. He hopped down from the cab and snaked a rubber hose to the kitchen. Then with the flip of a switch and a loud drone, the hose slurped the used cooking oil into the truck’s gleaming steel 2,200-gallon tank.

The spent grease that restaurants unload as waste has become a valuable commodity. If you’ve been on a plane lately, there’s a chance that used cooking oil has helped launch you into the sky. Refineries recycle waste oil into kerosene pure enough to power a Boeing 777. The process is expensive — but it can create 70 to 80 percent less planet-warming pollution than making jet fuel out of crude oil, experts say.

Last year, airlines burned 340 million gallons of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) — nearly all of it made from used cooking oil or animal fat leftover from meat packaging.

A series examining innovative and impactful approaches to addressing waste.

That’s a drop in the bucket compared to the 114 billion gallons of fuel airlines burned overall, which create 2.5 percent of humanity’s carbon pollution, according to the International Energy Agency. But airlines have vowed to use much more SAF to lower their greenhouse emissions. European regulators have set strict rules requiring airlines to use more SAF over time, while U.S. regulators dole out tax credits to coax companies into buying it.

This is the airlines’ main plan for dealing with their greenhouse emissions. Upgrading new planes with more efficient engines helps a little. And, one day, planes may run on electric batteries or hydrogen fuel cells — but those are still decades away and may never work for long flights. To manage most of their climate impact for the foreseeable future, airlines are betting everything on alternative fuels.

“Ninety-eight percent of [our greenhouse emissions] come from the fuel we burn,” said Lauren Riley, chief sustainability officer at United Airlines. “We’ll continue to look everywhere we can around technology and innovation of the aircraft itself and the engine, but we have to look at replacing our fuel.”

Experts say this plan can work, but it’ll require fuel refiners to dramatically raise SAF production and find new raw materials besides old cooking oil to turn into kerosene. Depending on what they use and how they refine it, this new class of fuel could make flying more sustainable or cause a whole new set of environmental headaches.

Harvesting the world’s grease

On his rounds one day in early May, Howell made about two dozen stops at commercial kitchens around Washington, including an upscale cafe in the Michelin Guide, an assisted-living facility, a soul food spot where old chicken bones clogged the hose and an Italian restaurant where two unfortunate rats had drowned in a grease bin while diving for a wayward meatball. By midafternoon, his truck had about 1,200 gallons of grease in its belly.

The company he works for, Mahoney Environmental, pays a few cents a gallon for the waste fat it collects from 90,000 businesses in the United States. Hundreds of companies gather grease around the globe — with an especially large haul in Southeast Asia, where densely packed restaurants serve up so much fried food that they’ve become the waste oil equivalent of Saudi Arabia’s rich petroleum fields.

Waste oil from kitchens and animal tallow leftover from meatpacking plants used to be recycled into livestock feed. But now, they are mostly turned into fuel: Fat molecules hold a lot of energy, and they’re relatively easy to rearrange into diesel and kerosene.

Turning fat into fuel keeps grease out of the landfill and petroleum in the ground. The demand, though, has begun to outstrip the supply.

“There’s only so many waste oils to go around, and … you can’t really squeeze out much more,” said Nikita Pavlenko, who leads the aviation and fuels team at the nonprofit International Council on Clean Transportation. “People aren’t going to be frying more food or processing more cattle to get waste tallow to make fuel. You’re kind of stuck with what you have.”

As regulators push companies to buy and make more fuel from fat, the price of grease has been rising, along with the crime surrounding it.

Thieves sometimes steal grease from collection bins and sell it themselves. Once, Howell said, he stopped at a restaurant only to find an empty bin and a confused cook, who told him an unmarked van had come by earlier and siphoned off their oil.

Grease fraud is a problem, too. In some areas, used cooking oil sells for more than new cooking oil, prompting hucksters to sell virgin oil — including palm oil, which is associated with deforestation in Southeast Asia — as if it were used. It’s hard to catch, since fresh oil spiked with a little restaurant grease is almost indistinguishable from the real thing.

“You’re potentially paying a premium for something that is worse than fossil fuel,” Pavlenko said.

Fuel companies crack down on fraud by hiring inspectors to go out and check that their grease suppliers really are pumping their product out of deep fat fryers. On his route, Howell takes pictures of every bin before and after he drains it and uploads the proof to a Mahoney Environmental app that verifies where his oil came from.

At the end of the day, Howell unloads his truck at a depot, where the oil is filtered to remove water, flour, spices and any other floating food chunks.

Turning fat into fuel

Used grease is a global commodity. Once it’s collected, tanker ships and pipelines carry it to fuel refineries around the world — much like they do for crude oil.

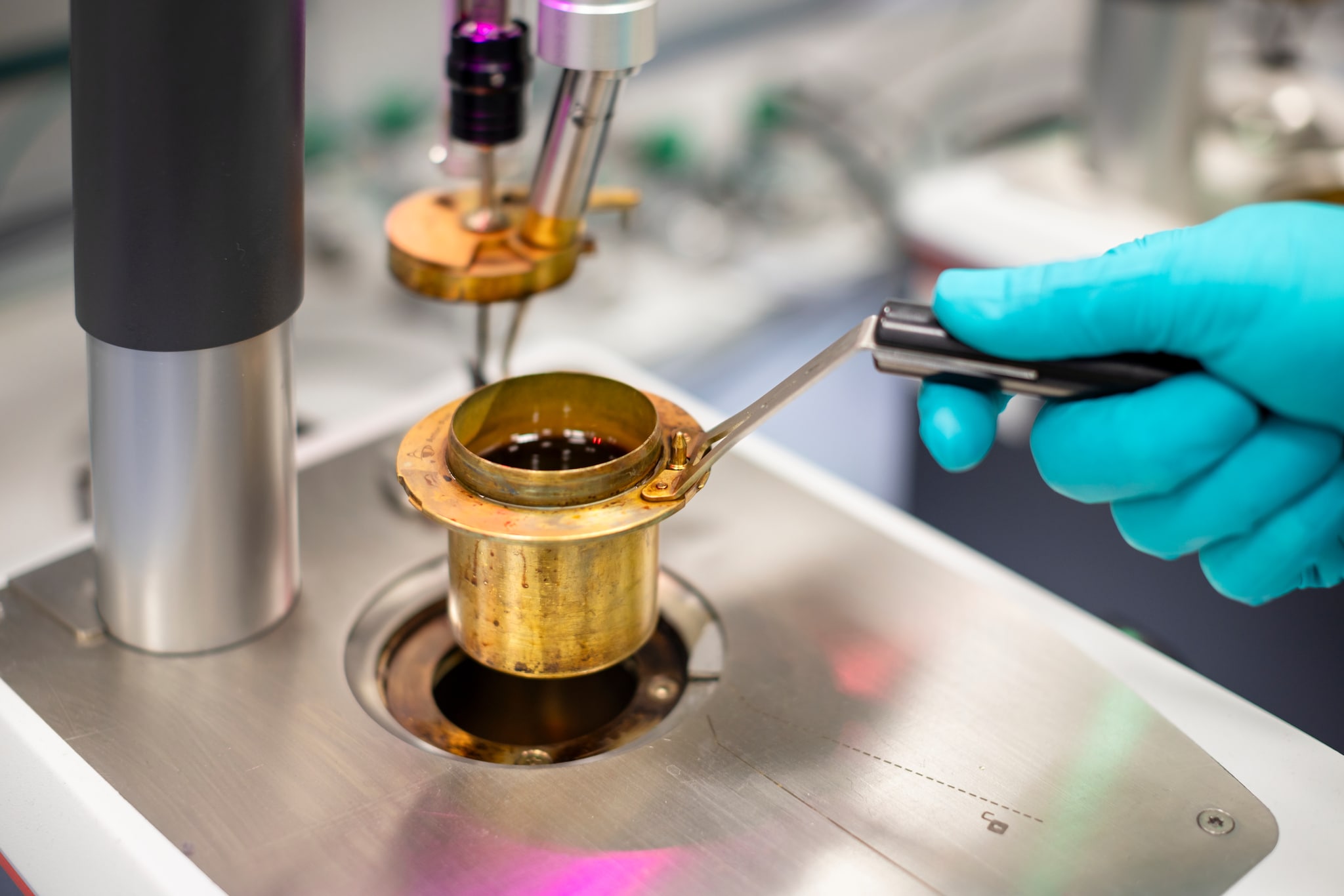

Grease ships arrive a couple of times a week at a refinery in Rotterdam run by Neste, the world’s top producer of sustainable jet fuel.

How grease is turned into jet fuel

Fueling the appetite for sustainable fuel

In 2023, a Boeing 777 flew across the Atlantic Ocean burning fuel made from nothing but waste fat and sugar. The flight was a first, but it was really a publicity stunt — carrying Virgin Atlantic bigwigs, not paying passengers. The fuel is too expensive, and too scarce, for that to make business sense.

Instead, Neste blends its french fry fuel with standard kerosene made from crude oil before delivering it to airports.

SAF is almost identical to standard jet fuel, and it releases just as much CO2 when it’s burned. But experts say there’s a key difference: Drilling for oil takes carbon that was locked away underground and releases it into the atmosphere. Making fuel from used cooking oil and tallow takes carbon that was already circulating through the air and the bodies of plants and animals and recycles it. No new carbon moves from underground storage into the atmosphere.

It takes energy to collect and transport used cooking oil, rearrange fat molecules into jet fuel and get that fuel to planes. But, overall, making and burning SAF adds as much as 80 percent less carbon to the atmosphere as making and burning fossil fuel from crude oil.

Because there isn’t enough waste oil in the world to satisfy the airline industry’s thirst, companies are developing other ways to make low-carbon jet fuel. One option is to grow more crops like soy that can be crushed for oil and turned into jet fuel — although that raises the risk that more land will be cleared for farming in fragile ecosystems like the Brazilian Amazon. Environmentalists have raised similar concerns about raising more corn, sugar cane or beets to create ethanol and convert it into kerosene.

“The problem with crop-based biofuels is it takes land to produce them at a time when we’re already expanding cropland … which means more deforestation, and the carbon losses are far greater than the potential savings from reducing fossil fuel use,” said Tim Searchinger, a senior research scholar at Princeton’s Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment.

Alternately, farmers could grow more cover crops on their fields between their regular planting seasons, which would create a new source of plant oils or ethanol without using extra land. Some companies have experimented with turning trash into jet fuel, but the most prominent player went bankrupt last year. Others are splitting water molecules to harvest their hydrogen and combining it with captured carbon to make fuel.

Experts say it will take a combination of all these methods to make enough green fuel to power the world’s planes.

The one thing every alternative fuel recipe has in common is that they are more expensive than fossil fuel — and experts say they always will be. Making SAF from waste oil is “locked in at a cost which is about two times the cost of fossil jet, and it’s going to be entirely reliant on subsidies,” according to Pavlenko. The other methods could be even more expensive, even after they’ve had time to raise production and lower costs.

The future of the industry will depend on whether the United States keeps tax credits in place and the European Union stands by its green fuel mandates. Neste is expanding its Rotterdam refinery in anticipation of stricter E.U. blending rules, and in the United States, the first large-scale SAF operations started pumping out fuel in recent years in response to new tax credits that have since been weakened.

Back at Le Diplomate, amid the evening dinner rush, frites flow out of the kitchen to feed hungry diners who are unwittingly helping launch planes into the sky with every bite.