Why Do Some People Always Get Lost?

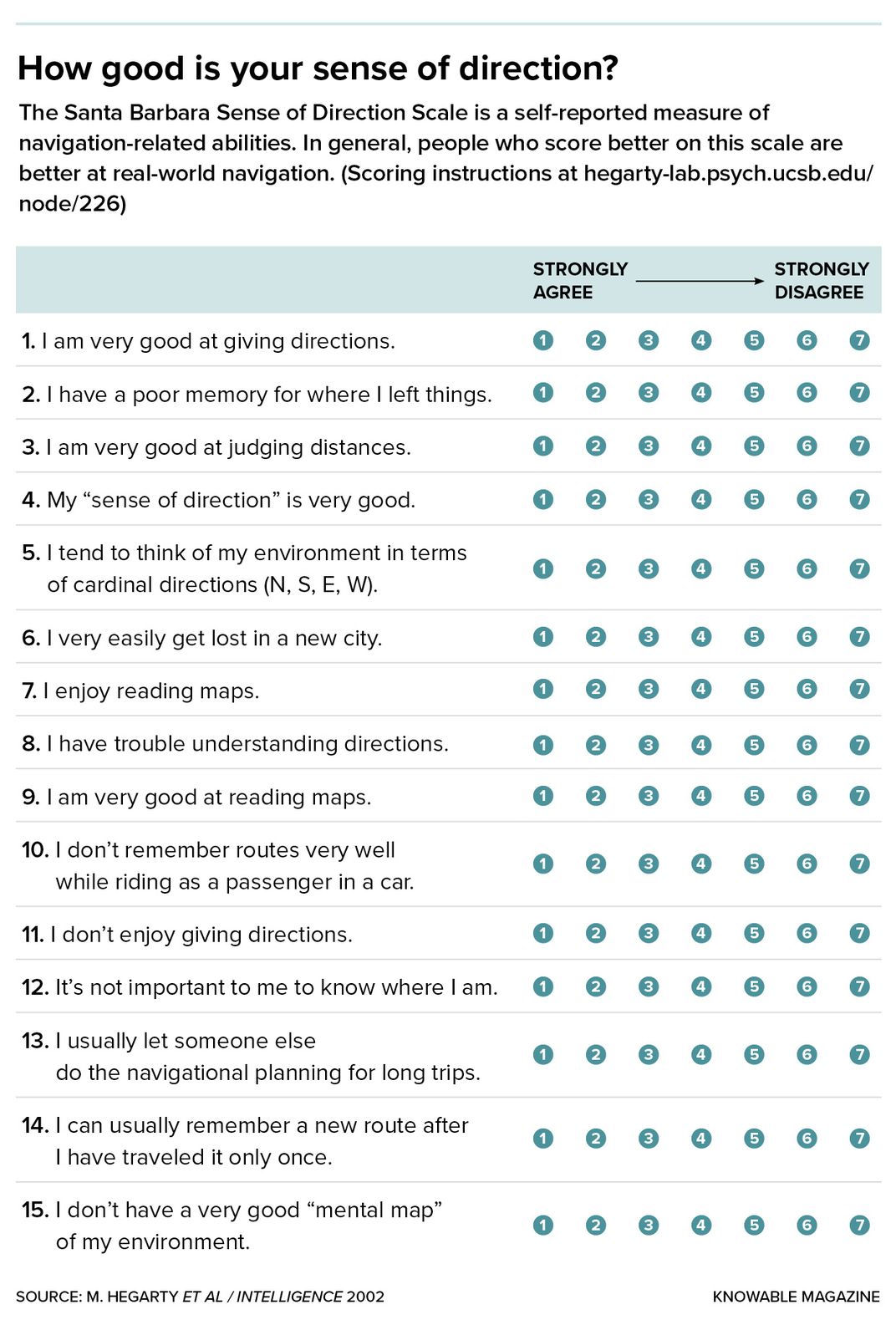

Like many of the researchers who study how people find their way from place to place, David Uttal is a poor navigator. “When I was 13 years old, I got lost on a Boy Scout hike, and I was lost for two and a half days,” recalls the Northwestern University cognitive scientist. And he’s still bad at finding his way around. The world is full of people like Uttal—and their opposites, the folks who always seem to know exactly where they are and how to get where they want to go. Scientists sometimes measure navigational ability by asking someone to point toward an out-of-sight location—or, more challenging, to imagine they are someplace else and point in the direction of a third location—and it’s immediately obvious that some people are better at it than others. “People are never perfect, but they can be as accurate as single-digit degrees off, which is incredibly accurate,” says Nora Newcombe, a cognitive psychologist at Temple University who was a co-author of a look at how navigational ability develops in the 2022 Annual Review of Developmental Psychology. But others, when asked to indicate the target’s direction, seem to point at random. “They have literally no idea where it is.” While it’s easy to show that people differ in navigational ability, it has proved much harder for scientists to explain why. There’s new excitement brewing in the navigation research world, though. By leveraging technologies such as virtual reality and GPS tracking, scientists have been able to watch hundreds, sometimes even millions, of people trying to find their way through complex spaces, and to measure how well they do. Though there’s still much to learn, the research suggests that to some extent, navigation skills are shaped by upbringing. Nurturing navigation skills The importance of a person’s environment is underscored by a recent look at the role of genetics in navigation. In 2020, Margherita Malanchini, a developmental psychologist at Queen Mary University of London, and her colleagues compared the performance of more than 2,600 identical and nonidentical twins as they navigated through a virtual environment, to test whether navigational ability runs in families. It does, they found—but only modestly. Instead, the biggest contributor to people’s performance was what geneticists call “nonshared environmental factors”—that is, the unique experiences each person accumulates as their life unfolds. Good navigators, it appears, are mostly made, not born. A remarkable, large-scale experiment led by Hugo Spiers, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, gave researchers a glimpse at how experience and other cultural factors might influence wayfinding skills. Spiers and his colleagues, in collaboration with the telecom company T-Mobile, developed a game for cellphones and tablets, “Sea Hero Quest,” in which players navigate by boat through a virtual environment to locate a series of checkpoints. The game app asked participants to provide basic demographic data, and nearly four million worldwide did so. (The app is no longer accepting new participants except by invitation of researchers.) Through the app, the researchers were able to measure wayfinding ability by the total distance each player traveled to reach all the checkpoints. After completing some levels of the game, players also had to shoot a flare back toward their point of origin—a dead-reckoning test analogous to the pointing-to-out-of-sight-locations task. Then Spiers and his colleagues could compare players’ performance to the demographic data. Several cultural factors were associated with wayfinding skills, they found. People from Nordic countries tended to be slightly better navigators, perhaps because the sport of orienteering, which combines cross-country running and navigation, is popular in those countries. Country folk did better, on average, than people from cities. And among city-dwellers, those from cities with more chaotic street networks such as those in the older parts of European cities did better than those from cities like Chicago, where the streets form a regular grid, perhaps because residents of grid cities don’t need to build such complex mental maps. Orienteering—a sport that combines cross-country running with map-based navigation—is popular in Nordic countries. This may be one reason why people from those countries tend to be better navigators than people from elsewhere. Border Liners Orienteering Club / Flickr Results like these suggest that an individual’s life experience may be one of the biggest determinants of how well they navigate. Indeed, experience may even underlie one of the most consistent findings—and clichés—in navigation: that men tend to perform better than women. Turns out this gender gap is more a question of culture and experience than of innate ability. Nordic countries, for example, where gender equality is greatest, show almost no gender difference in navigation. In contrast, men far outperform women in places where women face cultural restrictions on exploring their environment on their own, such as Middle Eastern countries. This cultural aspect, and the importance of experience, are also supported by studies of the Tsimane, a traditional Indigenous community in the Bolivian Amazon. Anthropologist Helen Elizabeth Davis of Arizona State University and her colleagues put GPS trackers on 305 Tsimane adults to measure their daily movements over a three-day period, and they found no difference in the distance moved by men and women. Men and women also were equally adept at pointing to out-of-sight locations, they reported in Topics in Cognitive Science. Even children performed extremely well at this navigation task—a result, Davis thinks, of growing up in a culture that encourages children to range widely and explore the forest. Most cultures aren’t like the Tsimane, though, and women and girls tend to be more cautious about exploring, for good reasons of personal safety. Not only do they gather less experience at navigating, but nervousness about security or getting lost also has a direct effect on navigation. “Anxiety gets in the way of good navigation, so if you’re worried about your personal safety, you’re a poor navigator,” says Newcombe. The Santa Barbara Sense of Direction Scale is widely used in navigation research. Studies suggest that people are fairly accurate at evaluating their own sense of direction. Hegarty et al. / Intelligence 2002 / Knowable Magazine Personality, too, appears to play a role in developing navigational ability. “To get good at navigating, you have to be willing to explore,” says Uttal. “Some people do not enjoy the experience of wandering, and others enjoy it very much.” Indeed, people who enjoy outdoor activities, such as hiking and biking, tend to have a better sense of direction, notes Mary Hegarty, a cognitive psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. So do people who play a lot of video games, many of which involve exploring virtual spaces. To Uttal, this accumulating evidence suggests that inclination and early experience nudge some people toward activities that involve navigation, while those who are temperamentally less inclined to explore, who have less opportunity to wander or who have an initial bad experience may be less likely to engage in activities that require exploration. It all snowballs from there, Uttal speculates. “I think a combination of personality and ability pushes you in certain directions. It’s a developmental cascade.” Mental mappers That cascade presumably influences acquisition of the specific skills that are hallmarks of good navigators. These include the ability to estimate how far you’ve traveled, to read and remember maps (both printed and mental), to learn routes based on a sequence of landmarks and to understand where points are relative to one another. Much of the research, though, has focused on two specific subskills: route-following by using landmarks—for example, turn left at the gas station, then go three blocks and turn right just past the red house—and what’s often termed “survey knowledge,” the ability to build and consult a mental map of a place. Of the two, route following is by far the easier task, and most people do pretty well at it once they’ve taken a route a few times, says Dan Montello, a geographer and psychologist also at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In a classic experiment from almost two decades ago, Montello’s student Toru Ishikawa drove 24 volunteers, once a week for ten weeks, on two twisting routes in a tony residential area of Santa Barbara that they’d never visited before. Later, almost every person could accurately state the order of landmarks along each route and roughly estimate the distance travelled between them. But they varied widely in their ability to identify shortcuts between the two routes, point to landmarks not visible from where they stood, or sketch a map of the routes. Those who couldn’t identify shortcuts or find landmarks may suffer from an inability to create accurate mental maps, the researchers think. Research by Newcombe and her then graduate student Steven Weisberg underscores the importance of such mental maps in navigation. They asked 294 volunteers to use a mouse and computer screen to navigate along two routes through a virtual town. Once the volunteers had learned the routes and the landmarks they contained, the researchers asked them to stand at one landmark and point to others on both routes. People fell into three classes, the researchers reported in 2018 in Current Directions in Psychological Science. Some people had formed a good mental map: They could point accurately to landmarks on both the same and different routes. Others had good route knowledge but struggled to create an integrated map: They were good at pointing within a route but poor between routes. A third group was poor at all the pointing tasks. That ability to build and refer to a mental map—a person’s survey knowledge—goes a long way toward explaining why they’re better navigators, Montello says. “When the only skill you have is the ability to think in terms of routes, you can’t be creative to get around barriers.” Survey knowledge gives the ability to navigate creatively, he says. “That’s a pretty stunning difference.” Not surprisingly, better navigators may also be better at switching modes and choosing the most appropriate navigational strategy for the situation they find themselves in, says cognitive neuroscientist Weisberg, now at the University of Florida. This could mean using landmarks when they are obvious and mental maps when more sophisticated calculations are needed. “I’ve moved toward thinking that our better navigators are also using a lot of alternate strategies,” Weisberg says. “And they’re doing so in a much more flexible way that affords different kinds of navigation, so that when they find themselves in a new situation, they’re better able to find their way.” For example, when Weisberg moves around Gainesville, where he lives now, he keeps track of north, because that works well in a city with a regular street grid; when he goes home to the winding streets of Philadelphia, he relies more on other cues to stay oriented. Researchers do not yet know whether every bad navigator is simply poor at survey knowledge, or whether some of the lost might be failing at other navigational subskills instead, such as remembering landmarks or estimating distance traveled. Either way, what can poor navigators do to improve? That’s still an open question. “We all have our pet theories,” says Elizabeth Chrastil, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, “but they haven’t reached the level of testing yet.” Pros and cons of GPS Simply practicing seems like it should work—and, indeed, it does in lab experiments. “We can improve people’s navigational abilities in virtual environments,” says Arne Ekstrom, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Arizona. It takes about two weeks to show fairly dramatic gains—but it’s not yet clear whether people are really becoming better navigators or just getting better at finding their way through the particular virtual environments used in the experiments. Support for the notion that people might improve with practice also comes from studies of what happens when people stop using their navigation skills. In a 2020 study published in Scientific Reports, for example, neuroscientists Louisa Dahmani and Véronique Bohbot of McGill University in Montreal recruited 50 young adults and questioned them about their lifetime experience of driving with GPS. Then they tested the volunteers in a virtual world that required them to navigate without GPS. The heaviest GPS users did worse, they found. A follow-up with 13 of the volunteers three years later revealed that those who had used GPS the most during the intervening period experienced greater declines in their ability to navigate without GPS, strongly suggesting that GPS reliance causes diminished skills, rather than poor skills leading to greater GPS use. Experts also suggest that struggling navigators like Uttal could try paying closer attention to compass directions or prominent landmarks as a way to integrate their movements into a mental map. For Weisberg, the only way he learns spaces in an integrated way is by paying attention to major cardinal directions or prominent landmarks like the ocean. “The more attention I pay, the better I can link things to the map in my head.” He recommends that struggling navigators ask themselves which way is north ten times a day, referring to a map if necessary. This, he suggests, could help them move beyond mere route knowledge. There’s another option for those who don’t really care about improving their skills as long as they just don’t get lost, Weisberg notes: Just make sure your GPS is handy.Knowable Magazine is an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Research suggests that experience may matter more than innate ability when it comes to a sense of direction

Like many of the researchers who study how people find their way from place to place, David Uttal is a poor navigator. “When I was 13 years old, I got lost on a Boy Scout hike, and I was lost for two and a half days,” recalls the Northwestern University cognitive scientist. And he’s still bad at finding his way around.

The world is full of people like Uttal—and their opposites, the folks who always seem to know exactly where they are and how to get where they want to go. Scientists sometimes measure navigational ability by asking someone to point toward an out-of-sight location—or, more challenging, to imagine they are someplace else and point in the direction of a third location—and it’s immediately obvious that some people are better at it than others.

“People are never perfect, but they can be as accurate as single-digit degrees off, which is incredibly accurate,” says Nora Newcombe, a cognitive psychologist at Temple University who was a co-author of a look at how navigational ability develops in the 2022 Annual Review of Developmental Psychology. But others, when asked to indicate the target’s direction, seem to point at random. “They have literally no idea where it is.”

While it’s easy to show that people differ in navigational ability, it has proved much harder for scientists to explain why. There’s new excitement brewing in the navigation research world, though. By leveraging technologies such as virtual reality and GPS tracking, scientists have been able to watch hundreds, sometimes even millions, of people trying to find their way through complex spaces, and to measure how well they do. Though there’s still much to learn, the research suggests that to some extent, navigation skills are shaped by upbringing.

Nurturing navigation skills

The importance of a person’s environment is underscored by a recent look at the role of genetics in navigation. In 2020, Margherita Malanchini, a developmental psychologist at Queen Mary University of London, and her colleagues compared the performance of more than 2,600 identical and nonidentical twins as they navigated through a virtual environment, to test whether navigational ability runs in families. It does, they found—but only modestly. Instead, the biggest contributor to people’s performance was what geneticists call “nonshared environmental factors”—that is, the unique experiences each person accumulates as their life unfolds. Good navigators, it appears, are mostly made, not born.

A remarkable, large-scale experiment led by Hugo Spiers, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, gave researchers a glimpse at how experience and other cultural factors might influence wayfinding skills. Spiers and his colleagues, in collaboration with the telecom company T-Mobile, developed a game for cellphones and tablets, “Sea Hero Quest,” in which players navigate by boat through a virtual environment to locate a series of checkpoints. The game app asked participants to provide basic demographic data, and nearly four million worldwide did so. (The app is no longer accepting new participants except by invitation of researchers.)

Through the app, the researchers were able to measure wayfinding ability by the total distance each player traveled to reach all the checkpoints. After completing some levels of the game, players also had to shoot a flare back toward their point of origin—a dead-reckoning test analogous to the pointing-to-out-of-sight-locations task. Then Spiers and his colleagues could compare players’ performance to the demographic data.

Several cultural factors were associated with wayfinding skills, they found. People from Nordic countries tended to be slightly better navigators, perhaps because the sport of orienteering, which combines cross-country running and navigation, is popular in those countries. Country folk did better, on average, than people from cities. And among city-dwellers, those from cities with more chaotic street networks such as those in the older parts of European cities did better than those from cities like Chicago, where the streets form a regular grid, perhaps because residents of grid cities don’t need to build such complex mental maps.

Results like these suggest that an individual’s life experience may be one of the biggest determinants of how well they navigate. Indeed, experience may even underlie one of the most consistent findings—and clichés—in navigation: that men tend to perform better than women. Turns out this gender gap is more a question of culture and experience than of innate ability.

Nordic countries, for example, where gender equality is greatest, show almost no gender difference in navigation. In contrast, men far outperform women in places where women face cultural restrictions on exploring their environment on their own, such as Middle Eastern countries.

This cultural aspect, and the importance of experience, are also supported by studies of the Tsimane, a traditional Indigenous community in the Bolivian Amazon. Anthropologist Helen Elizabeth Davis of Arizona State University and her colleagues put GPS trackers on 305 Tsimane adults to measure their daily movements over a three-day period, and they found no difference in the distance moved by men and women. Men and women also were equally adept at pointing to out-of-sight locations, they reported in Topics in Cognitive Science. Even children performed extremely well at this navigation task—a result, Davis thinks, of growing up in a culture that encourages children to range widely and explore the forest.

Most cultures aren’t like the Tsimane, though, and women and girls tend to be more cautious about exploring, for good reasons of personal safety. Not only do they gather less experience at navigating, but nervousness about security or getting lost also has a direct effect on navigation. “Anxiety gets in the way of good navigation, so if you’re worried about your personal safety, you’re a poor navigator,” says Newcombe.

Personality, too, appears to play a role in developing navigational ability. “To get good at navigating, you have to be willing to explore,” says Uttal. “Some people do not enjoy the experience of wandering, and others enjoy it very much.”

Indeed, people who enjoy outdoor activities, such as hiking and biking, tend to have a better sense of direction, notes Mary Hegarty, a cognitive psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. So do people who play a lot of video games, many of which involve exploring virtual spaces.

To Uttal, this accumulating evidence suggests that inclination and early experience nudge some people toward activities that involve navigation, while those who are temperamentally less inclined to explore, who have less opportunity to wander or who have an initial bad experience may be less likely to engage in activities that require exploration. It all snowballs from there, Uttal speculates. “I think a combination of personality and ability pushes you in certain directions. It’s a developmental cascade.”

Mental mappers

That cascade presumably influences acquisition of the specific skills that are hallmarks of good navigators. These include the ability to estimate how far you’ve traveled, to read and remember maps (both printed and mental), to learn routes based on a sequence of landmarks and to understand where points are relative to one another.

Much of the research, though, has focused on two specific subskills: route-following by using landmarks—for example, turn left at the gas station, then go three blocks and turn right just past the red house—and what’s often termed “survey knowledge,” the ability to build and consult a mental map of a place.

Of the two, route following is by far the easier task, and most people do pretty well at it once they’ve taken a route a few times, says Dan Montello, a geographer and psychologist also at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In a classic experiment from almost two decades ago, Montello’s student Toru Ishikawa drove 24 volunteers, once a week for ten weeks, on two twisting routes in a tony residential area of Santa Barbara that they’d never visited before.

Later, almost every person could accurately state the order of landmarks along each route and roughly estimate the distance travelled between them. But they varied widely in their ability to identify shortcuts between the two routes, point to landmarks not visible from where they stood, or sketch a map of the routes. Those who couldn’t identify shortcuts or find landmarks may suffer from an inability to create accurate mental maps, the researchers think.

Research by Newcombe and her then graduate student Steven Weisberg underscores the importance of such mental maps in navigation. They asked 294 volunteers to use a mouse and computer screen to navigate along two routes through a virtual town. Once the volunteers had learned the routes and the landmarks they contained, the researchers asked them to stand at one landmark and point to others on both routes.

People fell into three classes, the researchers reported in 2018 in Current Directions in Psychological Science. Some people had formed a good mental map: They could point accurately to landmarks on both the same and different routes. Others had good route knowledge but struggled to create an integrated map: They were good at pointing within a route but poor between routes. A third group was poor at all the pointing tasks.

That ability to build and refer to a mental map—a person’s survey knowledge—goes a long way toward explaining why they’re better navigators, Montello says. “When the only skill you have is the ability to think in terms of routes, you can’t be creative to get around barriers.” Survey knowledge gives the ability to navigate creatively, he says. “That’s a pretty stunning difference.”

Not surprisingly, better navigators may also be better at switching modes and choosing the most appropriate navigational strategy for the situation they find themselves in, says cognitive neuroscientist Weisberg, now at the University of Florida. This could mean using landmarks when they are obvious and mental maps when more sophisticated calculations are needed.

“I’ve moved toward thinking that our better navigators are also using a lot of alternate strategies,” Weisberg says. “And they’re doing so in a much more flexible way that affords different kinds of navigation, so that when they find themselves in a new situation, they’re better able to find their way.”

For example, when Weisberg moves around Gainesville, where he lives now, he keeps track of north, because that works well in a city with a regular street grid; when he goes home to the winding streets of Philadelphia, he relies more on other cues to stay oriented.

Researchers do not yet know whether every bad navigator is simply poor at survey knowledge, or whether some of the lost might be failing at other navigational subskills instead, such as remembering landmarks or estimating distance traveled. Either way, what can poor navigators do to improve? That’s still an open question. “We all have our pet theories,” says Elizabeth Chrastil, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, “but they haven’t reached the level of testing yet.”

Pros and cons of GPS

Simply practicing seems like it should work—and, indeed, it does in lab experiments. “We can improve people’s navigational abilities in virtual environments,” says Arne Ekstrom, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Arizona. It takes about two weeks to show fairly dramatic gains—but it’s not yet clear whether people are really becoming better navigators or just getting better at finding their way through the particular virtual environments used in the experiments.

Support for the notion that people might improve with practice also comes from studies of what happens when people stop using their navigation skills. In a 2020 study published in Scientific Reports, for example, neuroscientists Louisa Dahmani and Véronique Bohbot of McGill University in Montreal recruited 50 young adults and questioned them about their lifetime experience of driving with GPS. Then they tested the volunteers in a virtual world that required them to navigate without GPS. The heaviest GPS users did worse, they found.

A follow-up with 13 of the volunteers three years later revealed that those who had used GPS the most during the intervening period experienced greater declines in their ability to navigate without GPS, strongly suggesting that GPS reliance causes diminished skills, rather than poor skills leading to greater GPS use.

Experts also suggest that struggling navigators like Uttal could try paying closer attention to compass directions or prominent landmarks as a way to integrate their movements into a mental map. For Weisberg, the only way he learns spaces in an integrated way is by paying attention to major cardinal directions or prominent landmarks like the ocean. “The more attention I pay, the better I can link things to the map in my head.” He recommends that struggling navigators ask themselves which way is north ten times a day, referring to a map if necessary. This, he suggests, could help them move beyond mere route knowledge.

There’s another option for those who don’t really care about improving their skills as long as they just don’t get lost, Weisberg notes: Just make sure your GPS is handy.

Knowable Magazine is an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.