What's Killing These Oak Trees in the Midwest? Conservationists Believe Drifting Herbicides Are to Blame

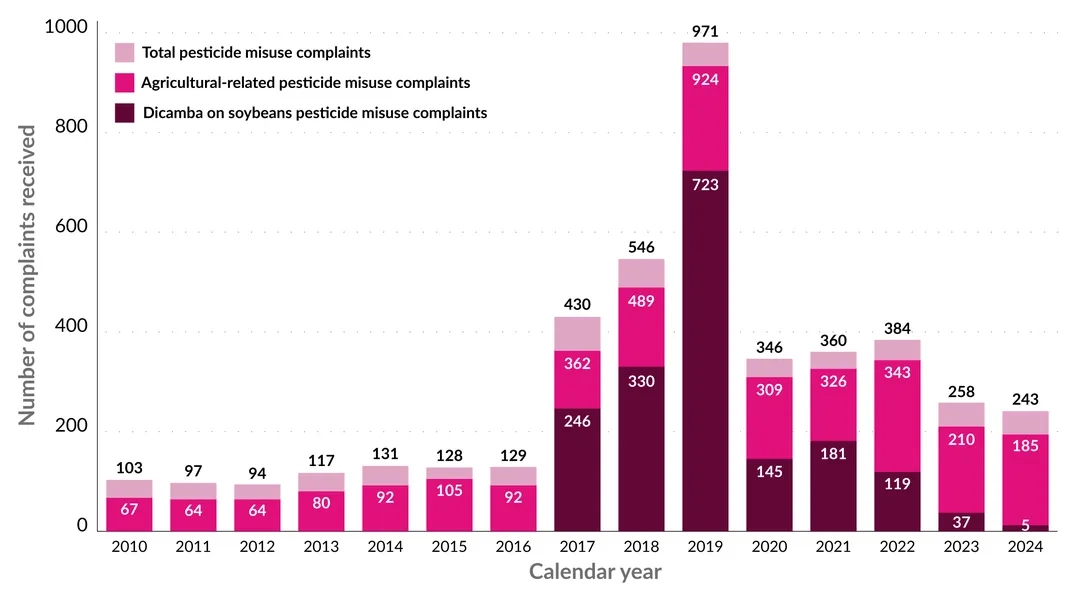

What’s Killing These Oak Trees in the Midwest? Conservationists Believe Drifting Herbicides Are to Blame When Illinois landowners noticed tree deaths and diseases on their properties ramp up in 2017, they suspected industrial agriculture. A survey found herbicides in 90 percent of tree tissues Christian Elliott, bioGraphic December 9, 2025 4:04 p.m. A dead tree stands with its bare, white trunk and branches in contrast to the greenery around it. Prairie Rivers Network Key takeaways: Herbicides and a blight of native oaks After the herbicide dicamba exploded in popularity among industrial farmers in 2017, some Illinois residents noticed curled and discolored leaves on native oak trees. Scientists and conservationists are gathering data in hopes of advocating for restrictions on herbicide use, such as tighter regulations on spraying in high winds. The symptoms were strange. They were the same across multiple oak species—white, swamp white, black, red, post, shingle, chinquapin, blackjack and pin. Leaves thickened, elongated and contorted into grotesque shapes—cupping, puckering, curling and twisting until it was hard to tell one species from another. Veins bleached yellow, losing chlorophyll. Soon after, some of the trees died. Seth Swoboda first noticed the sickness in the spring of 2017 on his 40-acre property in Nashville, Illinois, smack in the middle of some of the United States’ most productive farmland. He knocked on the door of his neighbor Martin Kemper and asked if there were some new oak disease going around. Kemper didn’t think so, but he had an idea. A retired biologist from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Kemper had noticed other oaks and native trees in the area showing similar signs of injury. He suspected a culprit that’s risky to blame in a state economically and politically steeped in agriculture: herbicide drift, or the movement of weed-killing chemicals onto nontarget plants. Swoboda’s property, a cattle pasture on oak-hickory woodland, is surrounded on four sides by industrial-scale corn and soybean operations. On a hot summer evening after a neighbor has sprayed their fields, you can smell the herbicide in the air. Heat, a stiff breeze or a temperature inversion can hoist the molecules into the atmosphere and carry them far away. In one study, researchers found that an herbicide had been carried in the clouds for over a hundred miles before falling as rain. Seth Swoboda first noticed signs of herbicide damage on the native oaks on his property in Nashville, Illinois, in 2017. Since then, he’s lost 11 trees. Christian Elliott Herbicide drift is internationally recognized as a problem for native species and closely tracked across Europe. Yet no government agency in Illinois or the surrounding states was measuring its impacts, even on the few patches of native forest left there, says Kim Erndt-Pitcher, an ecotoxicologist and director of ecological health for the Illinois-based nonprofit Prairie Rivers Network. “We met with agencies, and it was just really hard to convince folks that this is an issue,” Erndt-Pitcher adds. “No one was looking at the frequency of symptoms or the severity of symptoms or the distribution across the state.” So, Prairie Rivers Network started a monitoring program with a shoestring budget and a handful of volunteers. One of them was Kemper. Over the past seven years, Kemper and Erndt-Pitcher have driven to Swoboda’s farm and 279 other sites on public and private land to visually assess trees and collect tissue samples. Swoboda’s samples wait alongside Dilly Bars in his farmhouse freezer until Prairie Rivers Network can afford to ship them to a lab for chemical analysis, at a cost of around $900 per sample. Twenty of 21 samples analyzed from Swoboda’s land have come back positive for 2,4-D, dicamba, atrazine or other herbicides, and 53 plant species have shown herbicide exposure symptoms. Swoboda has filed formal misuse complaints to the Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDOA) each year to no avail. To prove wrongdoing, he needs evidence that’s nearly impossible get: a specific farmer to blame, a time and date for the application, and a wind speed or temperature above the legal limits specified on the product’s label at the time of spraying. In 2024, Prairie Rivers Network published the results of its monitoring program and revealed that 99.6 percent of test sites showed drift symptoms and 90 percent of tree tissue samples contained herbicides. A separate survey of 78,000 plants from nearly 200 sites, published the same year by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, found similar results, and nonprofits and land managers in other Midwestern states are likewise recording increasing herbicide damage. Scientists worry about potential cascading effects on insects, birds, reptiles and mammals, while locals like Swoboda are also concerned about human health impacts. At least 85 pesticides—an umbrella term for any chemical used to kill something, including insecticides, herbicides and fungicides—that are routinely used in the U.S. have been banned or are being phased out in other countries due to potential health risks, including links to cancers and other diseases. Kim Erndt-Pitcher, an ecotoxicologist and director of ecological health for the Illinois-based nonprofit Prairie Rivers Network, visits more than 275 sites each year to collect tissue samples and visually assess trees for signs of herbicide drift. Prairie Rivers Network “This is people’s personal property rights. This is their right to a healthful, clean environment, and it’s being violated on a regular basis, year after year,” says Erndt-Pitcher. “[The agrochemical] industry is incredibly powerful and influential. And I think if more people knew what all this meant—what we’re risking by inaction—they would be really mad. Like, really, really mad.” Today, on the Fourth of July holiday, Erndt-Pitcher, Kemper and I follow Swoboda around his property. He’s spent the morning cutting bush honeysuckle and multiflora rose—invasives encroaching on his oaks. The afternoon sun beats down through a much-thinned canopy onto a yard that, for generations, was so shaded the Swobodas didn’t have to mow. He points out the places where oaks used to be; out of 104 mature native hardwoods, he’s lost 11 since 2017, their trunks and branches now a pile of firewood on the gravel driveway. He plants new oaks, but they show the same signs of damage. Kemper bends down and beckons me over to look at the garden phlox planted next to the patio where Swoboda’s kids play. The plant’s leaves are cupped, too. Oak trees, native to Illinois and much of the U.S., offer habitat for insects, fungi, birds and mammals. Hank Erdmann / Alamy Stock Photo For the past 1,000 years, much of the Midwest looked something like Swoboda’s property. The region was a mosaic of mesic oak-hickory woodland, tallgrass prairie and seasonal wetlands maintained by rejuvenating fires set by Indigenous peoples. In less than a century, nearly all of these native ecosystems were plowed. Rich prairie soil was converted to monocultures of corn and soy sustained by government subsidies, fertilizers and over 100 million pounds of synthetic pesticides each year. The grain produced by these crop factories mainly feeds livestock and fills fuel tanks. Before World War II, farmers largely relied on mechanical tilling to control weeds. With the birth of the pesticide industry, though, they started using weed killers like glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto’s signature Roundup herbicide. Farmers initially sprayed the soil before planting, to avoid damaging their crops, but in the 1990s Monsanto debuted Roundup Ready corn and soybeans, genetically engineered to tolerate the herbicide. Soon, larger tractors with 100-foot boom arms were spraying chemicals faster and in greater volume, directly onto crops for the first time. Between 1990 and 2022, pesticide use per cropland area increased by 94 percent worldwide. But by the early 2010s, weeds that had evolved resistance to glyphosate had become widespread. Farmers then pivoted to a different class of herbicides known as plant growth regulators. One was 2,4-D, one of several ingredients in Agent Orange, the infamous chemical weapon of the Vietnam War. Another, dicamba, exploded in popularity in 2017, a year after dicamba-resistant soybeans hit the market. Dicamba is particularly volatile—days after it’s sprayed, molecules can turn into a gas and drift away, particularly in the heat of summer. Plants can “breathe in” the toxicant through pores on the underside of their leaves. The year that dicamba-resistant soybeans ramped up was the same year that Swoboda noticed oaks on his property starting to wither and die. The IDOA was simultaneously inundated with reports from farmers who hadn’t planted dicamba-resistant soybeans and whose crops were dying from herbicide drift. Tensions between farmers who planted dicamba-resistant soybeans and those who did not were so fraught that one farmworker in Arkansas shot and killed a neighbor who confronted him about drift. After farmers began planting soybeans engineered with a resistance to the herbicide dicamba in 2016 and 2017, allegations of pesticide misuse in Illinois jumped. Data by Illinois Department of Agriculture, design by Mark Garrison “Every extension weed scientist throughout the Midwest knew what was going to happen,” says Aaron Hager, a weed scientist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “We knew there was going to be an effect on trees. There’s no way there couldn’t have been an effect on trees.” The fields around Swoboda’s property have been actively farmed since before he was born 45 years ago. Only the chemicals have changed. “By the time I realized, it was too late, really,” he says. Crops are often engineered to resist multiple herbicides. Native species aren’t. The oaks, Swoboda says, “went fast.” A road near agricultural fields Charles O. Cecil / Alamy Stock Photo Since they took root some 50 million years ago, oaks have played an outsize role in North American ecosystems. The continent’s 250 or so species of oaks together make up more tree biomass than any other woody genus, and they shelter and feed a breadth of insects, fungi, birds and mammals. They grow slowly, adding just millimeters of girth each year, and what they lack in speed they make up for in strength and bulk. Some species can reach seven feet in diameter; others reach 100 feet into the sky. And while many native trees of North America have succumbed to introduced pests and diseases in the past century, oaks seemed largely impervious, their gnarled limbs often stretching so high overhead that early signs of damage are hard to notice. Once you learn to see the signs, though, you notice the destruction everywhere—even far from the nearest farmland. Leaving Swoboda behind, Kemper and Erndt-Pitcher take me on a whirlwind tour of state parks and nature preserves. At Eldon Hazlet State Recreation Area, Kemper stops so frequently to point out native trees with signs of herbicide damage—sweet gum, American elm, tulip poplar, shagbark hickory, persimmon, redbud, river birch, box elder—that Erndt-Pitcher begins to feel carsick in the back seat. She jokes he needs a pointer on a yardstick for Christmas and asks him to please, please turn on the air conditioning. In 2024, Prairie Rivers Network published the results of its monitoring program and revealed that 99.6 percent of test sites showed drift symptoms and 90 percent of tree tissue samples contained herbicides, resulting in cupped, puckered leaves, like those of this redbud. Prairie Rivers Network Even if herbicide effects aren’t directly lethal, some researchers believe that curled leaves, like these on a post oak, likely won’t photosynthesize as efficiently as regular leaves. Prairie Rivers Network In the park campground, at capacity on this holiday weekend, hundreds of RVs and tents sit in the dappled light of a sparse canopy. Some oaks sprout leaves from their branches and trunks in a last-ditch effort to photosynthesize, but many limbs are already dead. It’s easy to imagine this place in another few decades with no trees—or campers—left. “Lots of us that work on this issue, we’ll say we used to love the summer and the spring, and now it’s become a dreaded time of year, because it’s just this persistent series of wounds all around us that we have to observe,” says Erndt-Pitcher. Later, at Washington County State Recreation Area, we stop at a spit of land overlooking a lake. Kemper has come to this spot since he was 10 years old to watch Carolina chickadees, white-breasted nuthatches, tufted titmice, blue jays, woodpeckers and the occasional barred owl, along with other migratory and resident bird species. “This was a fantastic white oak-canopied area … and now it’s a disaster,” says Kemper. “And it’s scary, because what I see is a progression that’s slowly getting worse. We’re seeing a gradual decline in the health of the forest, and the chances that this doesn’t have ecological cascades, in my estimation, are zero.” Erndt-Pitcher points out that the state is legally obligated to protect designated nature preserves. But while years of environmental activism have left many people aware of how pesticide overuse harms pollinating insects and can contribute to cancers, Parkinson’s disease, birth defects and endocrine problems in humans, the dangers to native plants have made fewer headlines. In the 1970s, the state passed the Illinois Pesticide Act to protect people and the environment from pesticide misuse. But Erndt-Pitcher argues the act doesn’t do enough to address drift. And it’s enforced by the IDOA, which she sees as a conflict of interest. (Weeds can cut corn yields by 50 percent or more, and it’s in the state’s interest to maximize farm production.) The state Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defers to the IDOA on pesticides, while the federal EPA—which regulates 16,800 different pesticides—relies largely on studies conducted by agrochemical companies for its safety assessments. Agrochemical companies also spend tens of millions of dollars annually to lobby lawmakers and reportedly employ many former federal EPA employees. This year, Prairie Rivers Network proposed bills in the state legislature to ban a particularly volatile formulation of 2,4-D and to require herbicide applicators to notify nearby schools and parks before spraying. Neither passed. “We’ve been calling attention to this for over ten years,” says Kemper. “And those regulatory agencies that have this responsibility have not, to our knowledge, done enough to have an impact on the issue.” Martin Kemper, a retired biologist from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, volunteers with Prairie Rivers Network to monitor trees for signs of herbicide drift. Prairie Rivers Network In response, the IDOA says it operates “a training, certification and licensing program to ensure pesticide applicators are properly licensed and knowledgeable regarding pesticide use,” and that all “complaints of pesticide misuse are investigated by plant and pesticide specialists.” The IDOA also has the authority to implement state-specific regulations for individual pesticides like dicamba and supports a nonprofit, voluntary mapping registry. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources did not respond to a request to comment. In one small win for activists, a U.S. District Court in Arizona in 2024 overturned the federal approval of dicamba, essentially banning it across the U.S. for the 2025 growing season. But overall herbicide use is still increasing, and the Trump administration is considering reversing the ban on dicamba, citing confidence that if users apply the product as directed, it will “not pose an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment.” Additionally, the federal EPA’s scientific research arm, which serves as its foundation for assessing toxic chemicals, including herbicides, will likely be disbanded. To Erndt-Pitcher, that puts the onus on states. Yet while the IDOA and lawmakers have done little to solve the problem in activists’ eyes, Prairie Rivers Network’s small, volunteer-staffed monitoring program has helped convince other state agencies and universities to study the problem. Now, peer-reviewed lab experiments and field studies are beginning to show what landowners like Swoboda have been observing for years. A forest borders agricultural land in Illinois Prairie Rivers Network One of the scientists conducting lab experiments is wildlife ecologist T.J. Benson, whom I meet in a small room in the Illinois Natural History Survey lab at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Opening a white cabinet, he shows me tiny moth larvae wriggling in dozens of clear plastic deli containers. They’re black cutworms, a common native caterpillar and crop pest. Each container has a little flan-like cube of caterpillar food spiked with one of several pesticides. Benson buys the eggs and food from a company that presumably also sells to pesticide producers for insecticide testing. “The Insects You Need, When You Need Them,” reads the empty cardboard box. But Benson’s goals are different; he specializes in birds. He started this experiment after tracking declining eastern whippoorwill populations, which generally thrive when caterpillars are abundant. “Birds migrating through right now are very dependent on caterpillars that are feeding on these really young [tree] leaves,” he says. Yet when the federal EPA evaluates new herbicides for impacts to insects, it typically only considers non-native honeybees, Benson says—which don’t eat leaves. And the only birds considered in the agency’s models are usually mallard ducks and quails, which are not exclusively insectivorous and are larger-bodied, which could make them less susceptible than smaller species. When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency evaluates new herbicides for impacts to insects, it typically only considers non-native honeybees rather than bumblebees, says wildlife ecologist T.J. Benson. Prairie Rivers Network Benson regularly weighs individual caterpillars to study the effects of pesticides on their growth. He and his graduate student Grant Witynski have found that caterpillars exposed to field-realistic concentrations of atrazine and 2,4-D have up to a 26 percent lower probability of surviving to adulthood than controls. If caterpillars in the wild are regularly eating leaves contaminated by these herbicides, it could be harming whippoorwills and other insectivorous birds, as well as species that depend on oaks for habitat. Activists hope that such science will eventually give them the evidence they need to convince lawmakers and regulators to take action. For now, though, landowners who complain to state agriculture employees are often told that they can’t prove the visual symptoms they’re seeing on leaves are caused by herbicides in the plant tissues and not something else. And despite anecdotal evidence of tree death across the Midwest, controlled studies haven’t yet proved that the long-term effects of herbicides are deadly. Hager, the weed scientist, is among the skeptics. He knew that changes to herbicide use would result in greater drift, and that once people started noticing plant growth regulator symptoms in trees back in 2017, they’d eventually start looking for pesticides in leaf samples. But based on the available data, he doesn’t buy that drift is as big a crisis as some claim for the long-term health of trees, or that visual symptoms necessarily correlate with widespread tree mortality. “We could have pulled tree leaf samples any year in the last 50 years and found pesticides,” he tells me. “And we still have trees on the landscape.” Animals large and small depend on the few remaining native plants in a region dominated by industrial-scale agriculture. Prairie Rivers Network And while some advocates believe that the only answer is banning certain herbicides or even radically changing the way land is farmed in this part of the world, Hager and others argue that a statewide ban on any individual herbicide would put Illinois farmers at a competitive disadvantage. He’d like to see an amendment to the Illinois Pesticide Act that bans spraying when winds exceed a certain speed. But the state would need more staff and money to enforce a rule like that. At the Illinois Natural History Survey complex, Benson and botanist Ed Price lead me to a greenhouse. Inside, little potted oaks and redbuds sit in lines on tables. Some have been sprayed with herbicides multiple times in a year, others only once or not at all. So far, plants seem to be most vulnerable when they’re young, just as their buds swell and their leaves unfurl. Price and Benson are looking for residual damage—whether leaves regrow “wonky” in subsequent years after a lab-simulated drift event. The University of Missouri is running a similar study on ornamental and fruit trees. Price shows me a curled oak leaf. Even if herbicide effects aren’t directly lethal, he explains, curled leaves likely won’t photosynthesize as efficiently as regular leaves do. Trees face multiple stressors—higher temperatures, shifting seasons, more rainfall, drought, competition from invasive species. Herbicides are one of the few compounding stressors we have any immediate control over. And they could push stressed trees over the edge. As we walk back to the lab, Benson smells the medicinal odor of 2,4-D in the air. The facilities crew has just sprayed the landscaping for weeds. Back in Nashville, Illinois, American flags and firework stands line the streets for the Fourth of July holiday. Driving through, I notice curled, stunted leaves on redbuds in front of old Victorian homes decorated with red-white-and-blue bunting. Kemper is right—once you’ve learned what to look for, you see herbicide injury everywhere. Down the road from Swoboda’s farm, Kemper pulls his Ford Ranger pickup into a pasture. Just ahead is an imposing tree with a 17-foot circumference. Known as the Harper post oak, it is the largest post oak in the state. Using binoculars from my perch in the truck bed, I look up at the thickened, cupped leaves. The post oak has contained at least six types of herbicides from an average of three exposures per year since Prairie Rivers Network began sampling it. With a 17-foot circumference, the Harper post oak is the largest tree of its species in the state of Illinois. Prairie Rivers Network Larry Harper, the property owner, pulls up in a golf cart, sweating through his American flag T-shirt. He tells us that he had to cut down the last pin oak on his property this spring. With each year, as his only remaining post oak declines further, Harper gets increasingly mad. A state employee comes to his property regularly, responding to reports that go nowhere. “I just don’t know when it’s going to register,” he says. “Chestnut trees have been gone for a while. … Elm trees are gone. You’re going to lose all the oaks before you decide, ‘Hey, maybe we’ve got a problem?’” For now, though, the post oak still stands—gnarled, centuries old, towering over a pond on a pasture hilltop. We pause in its shade, bearing witness to yet another dying tree while everyone else in the county seems to be celebrating the Fourth of July with barbecues, fireworks and beer. Everyone, that is, except the farmworkers, who are out spraying pesticides even on the holiday, releasing a fine mist onto rows of corn and soy that stretch to the horizon. This story originally appeared in bioGraphic, an independent magazine about nature and regeneration powered by the California Academy of Sciences. Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

When Illinois landowners noticed tree deaths and diseases on their properties ramp up in 2017, they suspected industrial agriculture. A survey found herbicides in 90 percent of tree tissues

What’s Killing These Oak Trees in the Midwest? Conservationists Believe Drifting Herbicides Are to Blame

When Illinois landowners noticed tree deaths and diseases on their properties ramp up in 2017, they suspected industrial agriculture. A survey found herbicides in 90 percent of tree tissues

Christian Elliott, bioGraphic

Key takeaways: Herbicides and a blight of native oaks

- After the herbicide dicamba exploded in popularity among industrial farmers in 2017, some Illinois residents noticed curled and discolored leaves on native oak trees.

- Scientists and conservationists are gathering data in hopes of advocating for restrictions on herbicide use, such as tighter regulations on spraying in high winds.

The symptoms were strange. They were the same across multiple oak species—white, swamp white, black, red, post, shingle, chinquapin, blackjack and pin. Leaves thickened, elongated and contorted into grotesque shapes—cupping, puckering, curling and twisting until it was hard to tell one species from another. Veins bleached yellow, losing chlorophyll. Soon after, some of the trees died.

Seth Swoboda first noticed the sickness in the spring of 2017 on his 40-acre property in Nashville, Illinois, smack in the middle of some of the United States’ most productive farmland. He knocked on the door of his neighbor Martin Kemper and asked if there were some new oak disease going around.

Kemper didn’t think so, but he had an idea. A retired biologist from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Kemper had noticed other oaks and native trees in the area showing similar signs of injury. He suspected a culprit that’s risky to blame in a state economically and politically steeped in agriculture: herbicide drift, or the movement of weed-killing chemicals onto nontarget plants.

Swoboda’s property, a cattle pasture on oak-hickory woodland, is surrounded on four sides by industrial-scale corn and soybean operations. On a hot summer evening after a neighbor has sprayed their fields, you can smell the herbicide in the air. Heat, a stiff breeze or a temperature inversion can hoist the molecules into the atmosphere and carry them far away. In one study, researchers found that an herbicide had been carried in the clouds for over a hundred miles before falling as rain.

Herbicide drift is internationally recognized as a problem for native species and closely tracked across Europe. Yet no government agency in Illinois or the surrounding states was measuring its impacts, even on the few patches of native forest left there, says Kim Erndt-Pitcher, an ecotoxicologist and director of ecological health for the Illinois-based nonprofit Prairie Rivers Network. “We met with agencies, and it was just really hard to convince folks that this is an issue,” Erndt-Pitcher adds. “No one was looking at the frequency of symptoms or the severity of symptoms or the distribution across the state.” So, Prairie Rivers Network started a monitoring program with a shoestring budget and a handful of volunteers. One of them was Kemper.

Over the past seven years, Kemper and Erndt-Pitcher have driven to Swoboda’s farm and 279 other sites on public and private land to visually assess trees and collect tissue samples. Swoboda’s samples wait alongside Dilly Bars in his farmhouse freezer until Prairie Rivers Network can afford to ship them to a lab for chemical analysis, at a cost of around $900 per sample. Twenty of 21 samples analyzed from Swoboda’s land have come back positive for 2,4-D, dicamba, atrazine or other herbicides, and 53 plant species have shown herbicide exposure symptoms. Swoboda has filed formal misuse complaints to the Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDOA) each year to no avail. To prove wrongdoing, he needs evidence that’s nearly impossible get: a specific farmer to blame, a time and date for the application, and a wind speed or temperature above the legal limits specified on the product’s label at the time of spraying.

In 2024, Prairie Rivers Network published the results of its monitoring program and revealed that 99.6 percent of test sites showed drift symptoms and 90 percent of tree tissue samples contained herbicides. A separate survey of 78,000 plants from nearly 200 sites, published the same year by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, found similar results, and nonprofits and land managers in other Midwestern states are likewise recording increasing herbicide damage. Scientists worry about potential cascading effects on insects, birds, reptiles and mammals, while locals like Swoboda are also concerned about human health impacts. At least 85 pesticides—an umbrella term for any chemical used to kill something, including insecticides, herbicides and fungicides—that are routinely used in the U.S. have been banned or are being phased out in other countries due to potential health risks, including links to cancers and other diseases.

“This is people’s personal property rights. This is their right to a healthful, clean environment, and it’s being violated on a regular basis, year after year,” says Erndt-Pitcher. “[The agrochemical] industry is incredibly powerful and influential. And I think if more people knew what all this meant—what we’re risking by inaction—they would be really mad. Like, really, really mad.”

Today, on the Fourth of July holiday, Erndt-Pitcher, Kemper and I follow Swoboda around his property. He’s spent the morning cutting bush honeysuckle and multiflora rose—invasives encroaching on his oaks. The afternoon sun beats down through a much-thinned canopy onto a yard that, for generations, was so shaded the Swobodas didn’t have to mow. He points out the places where oaks used to be; out of 104 mature native hardwoods, he’s lost 11 since 2017, their trunks and branches now a pile of firewood on the gravel driveway. He plants new oaks, but they show the same signs of damage. Kemper bends down and beckons me over to look at the garden phlox planted next to the patio where Swoboda’s kids play. The plant’s leaves are cupped, too.

For the past 1,000 years, much of the Midwest looked something like Swoboda’s property. The region was a mosaic of mesic oak-hickory woodland, tallgrass prairie and seasonal wetlands maintained by rejuvenating fires set by Indigenous peoples. In less than a century, nearly all of these native ecosystems were plowed. Rich prairie soil was converted to monocultures of corn and soy sustained by government subsidies, fertilizers and over 100 million pounds of synthetic pesticides each year. The grain produced by these crop factories mainly feeds livestock and fills fuel tanks.

Before World War II, farmers largely relied on mechanical tilling to control weeds. With the birth of the pesticide industry, though, they started using weed killers like glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto’s signature Roundup herbicide. Farmers initially sprayed the soil before planting, to avoid damaging their crops, but in the 1990s Monsanto debuted Roundup Ready corn and soybeans, genetically engineered to tolerate the herbicide. Soon, larger tractors with 100-foot boom arms were spraying chemicals faster and in greater volume, directly onto crops for the first time. Between 1990 and 2022, pesticide use per cropland area increased by 94 percent worldwide.

But by the early 2010s, weeds that had evolved resistance to glyphosate had become widespread. Farmers then pivoted to a different class of herbicides known as plant growth regulators. One was 2,4-D, one of several ingredients in Agent Orange, the infamous chemical weapon of the Vietnam War. Another, dicamba, exploded in popularity in 2017, a year after dicamba-resistant soybeans hit the market. Dicamba is particularly volatile—days after it’s sprayed, molecules can turn into a gas and drift away, particularly in the heat of summer. Plants can “breathe in” the toxicant through pores on the underside of their leaves.

The year that dicamba-resistant soybeans ramped up was the same year that Swoboda noticed oaks on his property starting to wither and die. The IDOA was simultaneously inundated with reports from farmers who hadn’t planted dicamba-resistant soybeans and whose crops were dying from herbicide drift. Tensions between farmers who planted dicamba-resistant soybeans and those who did not were so fraught that one farmworker in Arkansas shot and killed a neighbor who confronted him about drift.

“Every extension weed scientist throughout the Midwest knew what was going to happen,” says Aaron Hager, a weed scientist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “We knew there was going to be an effect on trees. There’s no way there couldn’t have been an effect on trees.”

The fields around Swoboda’s property have been actively farmed since before he was born 45 years ago. Only the chemicals have changed. “By the time I realized, it was too late, really,” he says. Crops are often engineered to resist multiple herbicides. Native species aren’t. The oaks, Swoboda says, “went fast.”

Since they took root some 50 million years ago, oaks have played an outsize role in North American ecosystems. The continent’s 250 or so species of oaks together make up more tree biomass than any other woody genus, and they shelter and feed a breadth of insects, fungi, birds and mammals. They grow slowly, adding just millimeters of girth each year, and what they lack in speed they make up for in strength and bulk. Some species can reach seven feet in diameter; others reach 100 feet into the sky. And while many native trees of North America have succumbed to introduced pests and diseases in the past century, oaks seemed largely impervious, their gnarled limbs often stretching so high overhead that early signs of damage are hard to notice.

Once you learn to see the signs, though, you notice the destruction everywhere—even far from the nearest farmland.

Leaving Swoboda behind, Kemper and Erndt-Pitcher take me on a whirlwind tour of state parks and nature preserves. At Eldon Hazlet State Recreation Area, Kemper stops so frequently to point out native trees with signs of herbicide damage—sweet gum, American elm, tulip poplar, shagbark hickory, persimmon, redbud, river birch, box elder—that Erndt-Pitcher begins to feel carsick in the back seat. She jokes he needs a pointer on a yardstick for Christmas and asks him to please, please turn on the air conditioning.

In the park campground, at capacity on this holiday weekend, hundreds of RVs and tents sit in the dappled light of a sparse canopy. Some oaks sprout leaves from their branches and trunks in a last-ditch effort to photosynthesize, but many limbs are already dead. It’s easy to imagine this place in another few decades with no trees—or campers—left.

“Lots of us that work on this issue, we’ll say we used to love the summer and the spring, and now it’s become a dreaded time of year, because it’s just this persistent series of wounds all around us that we have to observe,” says Erndt-Pitcher.

Later, at Washington County State Recreation Area, we stop at a spit of land overlooking a lake. Kemper has come to this spot since he was 10 years old to watch Carolina chickadees, white-breasted nuthatches, tufted titmice, blue jays, woodpeckers and the occasional barred owl, along with other migratory and resident bird species. “This was a fantastic white oak-canopied area … and now it’s a disaster,” says Kemper. “And it’s scary, because what I see is a progression that’s slowly getting worse. We’re seeing a gradual decline in the health of the forest, and the chances that this doesn’t have ecological cascades, in my estimation, are zero.”

Erndt-Pitcher points out that the state is legally obligated to protect designated nature preserves. But while years of environmental activism have left many people aware of how pesticide overuse harms pollinating insects and can contribute to cancers, Parkinson’s disease, birth defects and endocrine problems in humans, the dangers to native plants have made fewer headlines. In the 1970s, the state passed the Illinois Pesticide Act to protect people and the environment from pesticide misuse. But Erndt-Pitcher argues the act doesn’t do enough to address drift. And it’s enforced by the IDOA, which she sees as a conflict of interest. (Weeds can cut corn yields by 50 percent or more, and it’s in the state’s interest to maximize farm production.) The state Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defers to the IDOA on pesticides, while the federal EPA—which regulates 16,800 different pesticides—relies largely on studies conducted by agrochemical companies for its safety assessments. Agrochemical companies also spend tens of millions of dollars annually to lobby lawmakers and reportedly employ many former federal EPA employees.

This year, Prairie Rivers Network proposed bills in the state legislature to ban a particularly volatile formulation of 2,4-D and to require herbicide applicators to notify nearby schools and parks before spraying. Neither passed.

“We’ve been calling attention to this for over ten years,” says Kemper. “And those regulatory agencies that have this responsibility have not, to our knowledge, done enough to have an impact on the issue.”

In response, the IDOA says it operates “a training, certification and licensing program to ensure pesticide applicators are properly licensed and knowledgeable regarding pesticide use,” and that all “complaints of pesticide misuse are investigated by plant and pesticide specialists.” The IDOA also has the authority to implement state-specific regulations for individual pesticides like dicamba and supports a nonprofit, voluntary mapping registry. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources did not respond to a request to comment.

In one small win for activists, a U.S. District Court in Arizona in 2024 overturned the federal approval of dicamba, essentially banning it across the U.S. for the 2025 growing season. But overall herbicide use is still increasing, and the Trump administration is considering reversing the ban on dicamba, citing confidence that if users apply the product as directed, it will “not pose an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment.” Additionally, the federal EPA’s scientific research arm, which serves as its foundation for assessing toxic chemicals, including herbicides, will likely be disbanded. To Erndt-Pitcher, that puts the onus on states.

Yet while the IDOA and lawmakers have done little to solve the problem in activists’ eyes, Prairie Rivers Network’s small, volunteer-staffed monitoring program has helped convince other state agencies and universities to study the problem. Now, peer-reviewed lab experiments and field studies are beginning to show what landowners like Swoboda have been observing for years.

One of the scientists conducting lab experiments is wildlife ecologist T.J. Benson, whom I meet in a small room in the Illinois Natural History Survey lab at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Opening a white cabinet, he shows me tiny moth larvae wriggling in dozens of clear plastic deli containers. They’re black cutworms, a common native caterpillar and crop pest. Each container has a little flan-like cube of caterpillar food spiked with one of several pesticides. Benson buys the eggs and food from a company that presumably also sells to pesticide producers for insecticide testing. “The Insects You Need, When You Need Them,” reads the empty cardboard box. But Benson’s goals are different; he specializes in birds. He started this experiment after tracking declining eastern whippoorwill populations, which generally thrive when caterpillars are abundant.

“Birds migrating through right now are very dependent on caterpillars that are feeding on these really young [tree] leaves,” he says. Yet when the federal EPA evaluates new herbicides for impacts to insects, it typically only considers non-native honeybees, Benson says—which don’t eat leaves. And the only birds considered in the agency’s models are usually mallard ducks and quails, which are not exclusively insectivorous and are larger-bodied, which could make them less susceptible than smaller species.

Benson regularly weighs individual caterpillars to study the effects of pesticides on their growth. He and his graduate student Grant Witynski have found that caterpillars exposed to field-realistic concentrations of atrazine and 2,4-D have up to a 26 percent lower probability of surviving to adulthood than controls. If caterpillars in the wild are regularly eating leaves contaminated by these herbicides, it could be harming whippoorwills and other insectivorous birds, as well as species that depend on oaks for habitat.

Activists hope that such science will eventually give them the evidence they need to convince lawmakers and regulators to take action. For now, though, landowners who complain to state agriculture employees are often told that they can’t prove the visual symptoms they’re seeing on leaves are caused by herbicides in the plant tissues and not something else. And despite anecdotal evidence of tree death across the Midwest, controlled studies haven’t yet proved that the long-term effects of herbicides are deadly.

Hager, the weed scientist, is among the skeptics. He knew that changes to herbicide use would result in greater drift, and that once people started noticing plant growth regulator symptoms in trees back in 2017, they’d eventually start looking for pesticides in leaf samples. But based on the available data, he doesn’t buy that drift is as big a crisis as some claim for the long-term health of trees, or that visual symptoms necessarily correlate with widespread tree mortality. “We could have pulled tree leaf samples any year in the last 50 years and found pesticides,” he tells me. “And we still have trees on the landscape.”

And while some advocates believe that the only answer is banning certain herbicides or even radically changing the way land is farmed in this part of the world, Hager and others argue that a statewide ban on any individual herbicide would put Illinois farmers at a competitive disadvantage. He’d like to see an amendment to the Illinois Pesticide Act that bans spraying when winds exceed a certain speed. But the state would need more staff and money to enforce a rule like that.

At the Illinois Natural History Survey complex, Benson and botanist Ed Price lead me to a greenhouse. Inside, little potted oaks and redbuds sit in lines on tables. Some have been sprayed with herbicides multiple times in a year, others only once or not at all. So far, plants seem to be most vulnerable when they’re young, just as their buds swell and their leaves unfurl. Price and Benson are looking for residual damage—whether leaves regrow “wonky” in subsequent years after a lab-simulated drift event. The University of Missouri is running a similar study on ornamental and fruit trees.

Price shows me a curled oak leaf. Even if herbicide effects aren’t directly lethal, he explains, curled leaves likely won’t photosynthesize as efficiently as regular leaves do. Trees face multiple stressors—higher temperatures, shifting seasons, more rainfall, drought, competition from invasive species. Herbicides are one of the few compounding stressors we have any immediate control over. And they could push stressed trees over the edge.

As we walk back to the lab, Benson smells the medicinal odor of 2,4-D in the air. The facilities crew has just sprayed the landscaping for weeds.

Back in Nashville, Illinois, American flags and firework stands line the streets for the Fourth of July holiday. Driving through, I notice curled, stunted leaves on redbuds in front of old Victorian homes decorated with red-white-and-blue bunting. Kemper is right—once you’ve learned what to look for, you see herbicide injury everywhere.

Down the road from Swoboda’s farm, Kemper pulls his Ford Ranger pickup into a pasture. Just ahead is an imposing tree with a 17-foot circumference. Known as the Harper post oak, it is the largest post oak in the state. Using binoculars from my perch in the truck bed, I look up at the thickened, cupped leaves. The post oak has contained at least six types of herbicides from an average of three exposures per year since Prairie Rivers Network began sampling it.

Larry Harper, the property owner, pulls up in a golf cart, sweating through his American flag T-shirt. He tells us that he had to cut down the last pin oak on his property this spring. With each year, as his only remaining post oak declines further, Harper gets increasingly mad. A state employee comes to his property regularly, responding to reports that go nowhere.

“I just don’t know when it’s going to register,” he says. “Chestnut trees have been gone for a while. … Elm trees are gone. You’re going to lose all the oaks before you decide, ‘Hey, maybe we’ve got a problem?’”

For now, though, the post oak still stands—gnarled, centuries old, towering over a pond on a pasture hilltop. We pause in its shade, bearing witness to yet another dying tree while everyone else in the county seems to be celebrating the Fourth of July with barbecues, fireworks and beer. Everyone, that is, except the farmworkers, who are out spraying pesticides even on the holiday, releasing a fine mist onto rows of corn and soy that stretch to the horizon.

This story originally appeared in bioGraphic, an independent magazine about nature and regeneration powered by the California Academy of Sciences.