We need to grow the economy. We need to stop torching the planet. Here’s how we do both.

The first thing that struck me about this year’s most talked-about policy book, Abundance (perhaps you’ve heard of it?), is a detail almost no one talks about. The book’s cover art sketches a future where half of our planet is densely woven with the homes, clean energy, and other technologies required to fill every human need, liberating the other half to flourish as a preserve for the biosphere on which we all depend — wild animals, forests, contiguous stretches of wilderness. It’s a beautiful ecomodernist image, suggesting that protecting what we might crudely call “nature” is an equal part of what it means to be prosperous, and that doing so is compatible with continued economic growth. It’s a visual rebuke to those who argue that we must choose between the two. How would we do it? The US and its peer countries today are spectacularly rich — unimaginably so, from the vantage of nearly any point in human history — and it might be tempting to think that we have grown enough, that our environmental crisis is so grave that we should save our planet by shrinking our economy and freeing ourselves from useless junk. I understand the pull of that vision — but it’s one that I think is illusory and politically calamitous, not to mention at odds with human freedom. A world where economic growth goes into reverse is a world that would see ever more brutal fighting over shrinking wealth, and it is far from guaranteed to benefit the planet. Yet that doesn’t change the essential problem: Climate change and the destruction of the natural world pose grave immediate threats to humans, and to the nonhuman life that is valuable in itself. And we are not on track to manage it. It’s not easy to reconcile these realities, but it is possible and necessary to do so in a way that’s consistent with liberal democratic principles. Instead of deliberately shrinking national income, we can seek out the areas of greatest inefficiency in our economy and chart a path that gets the most economic gain for the least environmental harm. If growing the economy without torching the planet is feasible in principle — and I think it is — then we should fight for it to grow in the best direction possible. Inside this story • Meat and dairy, plus our extreme dependence on cars, are two huge efficiency sinks: they produce a big share of emissions and devour land, and they aren’t essential to economic growth or human flourishing. • Shifting diets toward plant-based foods and freeing up land could act like a giant carbon-capture project, buying time to decarbonize. • Reducing car dependence would slash transport emissions, make land use more efficient, and make Americans healthier and safer — without sacrificing prosperity. We’ll need to build out renewables at breakneck speed and electrify everything we can, of course. But some of the most powerful levers we have to decouple economic growth from environmental impact challenge us to do something even harder — to begin outgrowing two central fixtures of American life that are as taken-for-granted as they are supremely inefficient: our extreme dependence on meat and cars. Changing those realities is so culturally and politically heretical in America that this case is almost never made in climate politics, but it deserves to be made nonetheless. And doing so will require examining the trade-offs that we too often treat as defaults. Two great efficiency sinks It’s probably not news to you that cars and animal-based foods are bad for the planet — together they contribute around a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions both globally and within the US. Animal agriculture also devours more than a third of habitable land globally (a crucially important part of our planetary crisis) and 40 percent of land in the lower 48 US states, while car-dependent sprawl fragments and eats into what’s left at the urban fringe. We obviously need food and transportation, but meat and cars convert our planet’s resources into those necessities much more wastefully than the alternatives: plant-based food, walking, public transportation, and so on. And in a climate-constrained economy that still needs to grow, we don’t have room to waste. Beef emits roughly 70 times more greenhouse gases per calorie than beans and 31 times more than tofu; poultry emits 10 times more than beans and four to five times more than tofu. Mile-for-mile, traveling by rail transit in the US emits about a third as much as driving on average, while walking doesn’t emit anything. For all that resource use, animal agriculture and autos are not indispensable to our economy or to our continued economic growth. The entire US agricultural sector, plus the manufacture and servicing of automobiles, make up a tiny share of our GDP; like other advanced economies, America’s is largely service-based, employing workers in everything from health care to law firms to restaurants and retailers like Amazon and Walmart. Of course, agriculture, energy, and manufacturing are foundational to everything else in the economy — without farming, Chipotle and Trader Joe’s would have no food to sell, and more importantly, we would starve. To say that agriculture isn’t a major part of our economy isn’t to say that it’s not really important to having an economy. But it is, unsurprisingly, those foundational parts of the economy that disproportionately drive resource use and environmental impact — and because they’re a small share of the economy, we have a lot of room to change their composition without crashing GDP. If we shifted a chunk of our food production away from meat and dairy and toward plant-based foods, for example, the already economically tiny ag sector might shrink somewhat. Meanwhile, we would save a lot of greenhouse gas emissions and land, and it would be reasonable to infer that the food service and retail sectors, which make up a significantly larger share of US GDP than agriculture does, would function all the same because we’d still eat the same number of calories and buy the same amount of food. With less meat consumption, the US might even have a significantly bigger alternative protein sector, with cleaner, better jobs than farm or slaughterhouse work. Which is not to say there wouldn’t be any losers in the short run — job losses and stranded capital in industries that are regionally concentrated and politically powerful. But those transitions can be managed, just as we have been managing the transition away from fossil fuels. This is exactly what decoupling — the idea that we can grow richer while decreasing emissions and other environmental impacts — looks like. The US, like a lot of other developed countries, has largely managed that in carbon emissions from energy consumption, which have fallen around 20 percent since 2005, even as the economy has grown about 50 percent in real terms. Agriculture has become more efficient, too, but it still lags on decoupling; the sector’s emissions are mostly flat or rising. Road transport tells a similar story: cars and trucks have gotten more efficient, but total emissions from driving are still stuck near their mid-2000s levels. Admittedly, it’s easier to decouple for energy than it is to change the way we eat or move around. A megawatt is a megawatt, whether it’s produced by coal or solar, while switching from steak to beans is not the same experience. But learning how to use resources more efficiently is, after all, a big part of how wealthy nations have become wealthy, including in these tougher sectors. Despite how inefficient our food system still is, the US has managed to significantly decrease how much land it uses for farming over the last century, while producing much more food. We could go much further if we weren’t so reliant on eating animals. Now, you might be thinking, so what if American GDP doesn’t depend on meat and cars? People like them, and they’re part of what it means to be rich and comfortable in the modern world. And you would have a point. No one would say that heating and cooling shouldn’t exist (well, the French might) just because they use a lot of energy and make up a tiny share of the economy. But every choice we make in the economy is a trade-off against something else, and everything we spend our limited carbon budget on is a choice to forgo something else. Our task is to decide whether high meat intake and extreme car dependence are worth that trade — whether they make up for their toll on the planet in contributions to our economy or to our flourishing as human beings. The “eating-the-Earth” problem We can start with animal agriculture, because however bad for the planet it looks on first impression, it’s actually worse. Estimates of the livestock industry’s greenhouse gas emissions range from around 12 to 20 percent globally; in the US, it’s around 7 percent (despite the lower percentage, per capita meat consumption is substantially higher in the US than it is globally — it’s just that our other sources of emissions are even higher). But those numbers don’t account for what climate scientists call the carbon opportunity cost of animal agriculture’s land use. This story was first featured in the Processing Meat newsletter Sign up here for Future Perfect’s biweekly newsletter from Marina Bolotnikova and Kenny Torrella, exploring how the meat and dairy industries shape our health, politics, culture, environment, and more. Have questions or comments on this newsletter? Email us at futureperfect@vox.com! Recall that farming animals for food takes up a massive amount of land, because we need space for the animals and for the crops needed to feed them. Meat and dairy production hogs 80 percent of all agricultural land to produce what amounts to 17 percent of global calories. Much of it could instead be rewilded with climate-stabilizing ecosystems, which would support biodiversity and also happen to be among our best defenses against global warming because of how good they are at sequestering carbon. How big would the impact be? The canonical paper on the carbon opportunity cost of animal agriculture finds that a 70 percent reduction in global meat consumption, relative to projected consumption levels in 2050, would remove the equivalent of about nine years of carbon emissions, while a global plant-based diet would remove 16 years of emissions; another study concludes that a rapid phaseout of animal agriculture could effectively freeze increases in all greenhouse gases over the next 30 years, and offset most carbon emissions this century. It’s worth pausing to appreciate just how miraculous that is. Freeing up even some of the land now used for meat and dairy turns it into a negative-emissions machine better than any existing carbon capture technology, giving us a carbon budget windfall that could ease the phaseout of fossil fuels and buy time for solving harder problems like decarbonizing aviation. This is as close as it gets to a free lunch, as long as you’re willing to make it a vegan lunch. Organizing society around cars doesn’t make sense We can think of car dependence as the other big resource black hole in US society. Transportation is the top source of greenhouse gas emissions in the country, and cars are the biggest source within that category, accounting for about 16 percent of all US emissions. Globally, gas-powered cars are in retreat — a very good thing for both climate change and deadly air pollution, though the US is increasingly falling behind peer countries in auto electrification. Still, if it were just a matter of swapping out gas-guzzlers for EVs, auto transportation wouldn’t be an obstacle to truly sustainable growth. But EVs alone aren’t a silver bullet for repairing the environmental problems of cars. One influential paper on the subject found as much in 2020, concluding that, at any realistic pace of electrification, EV growth wouldn’t be enough to meet climate targets, and even with universal adoption, EVs aren’t emissions-free. They take lots of energy to make — especially those heavy batteries — and an enormous amount of steel and critical minerals. These are scarce inputs that we also need to decarbonize the electric grid and build other green infrastructure. That isn’t to say that EVs aren’t better for the climate than gas-powered vehicles — they absolutely are. But as the lead author of that paper wrote in an accompanying commentary, “The real question is, do you even need a car?” The problem is not the existence of cars, but our total dependence on them. In most of the country, Americans have no other convenient transportation options. And remember, we’re trying to optimize for the least resources used for the most economic upside. Organizing society around the movement of hundreds of millions of two-ton metal boxes is… obviously not that, and the reasons why go well beyond emissions from the cars themselves. The car-dependent urban form that dominates America forces us to build things spread far apart — sprawl, in other words — which forces us to use more land. As of 2010, according to one estimate, the US devoted a land area about the size of New Jersey to parking spots alone. Our cities and suburbs occupy less than one-tenth as much land as farming — about 3 percent of the US total — but they still matter for the environment, fragmenting the habitats on which wildlife and ecosystems depend. Plus, housing in the US is sprawling enough that some exurban communities stretch across outlying rural counties, occupying an unknown additional share of land that’s not included in the 3 percent figure. Perhaps most damaging from an economic perspective, the sprawling development pattern that car dependence both enables and relies upon has driven the misallocation of valuable land toward low-density single-family homes, driving our national housing crisis. Cars are by no means the sole reason behind the housing shortage, but without mass car dependence, it would be vastly harder to lock so much of our land into inefficient uses. Meanwhile, Americans pay dearly for car dependence in the form of costly infrastructure and tens of thousands of traffic deaths each year. Urbanists sometimes like to say that the US prioritizes cars over people — that an alien arriving on Earth would probably think cars are our planet’s apex species. In some senses, that’s certainly true — the privileges that we’ve reserved for cars make it harder to meet the basic human need of housing, which makes us poorer and diminishes the agglomeration effects that make cities dynamic and productive. One widely cited paper estimated, astonishingly, that housing supply constraints, especially in the highest-productivity cities, cut US economic growth by 36 percent, relative to what it would have been otherwise, from 1964 to 2009. Imagine how much higher the GDP of Los Angeles would be if it doubled its housing stock and population and, with its freeways already maxed out, enabled millions more people to get around on foot, bike, and transit. And, of course, since autos and animal products are both very high in negative externalities, the benefits of reducing our collective dependence on them go well beyond the strictly economic or environmental. Americans would spend less money managing chronic disease and die fewer premature deaths (in the case of meat and dairy, probably, and in the case of cars, undoubtedly). We would torture and kill fewer animals (and fewer people would have to spend their working lives doing the killing). We would help keep antibiotics working, and we might even prevent the next pandemic. But will we do it? The growth that brought us industrial modernity is an awe-inspiring thing: It’s given us an abundance of choices, and it’s made obsolete brutal ways of life that not long ago were a shorthand for prosperity, like coal mining or the hunting of whales to make industrial products. Prosperity can be measured concretely in rising incomes and lengthening lifespans, but it’s also an evolving story we tell ourselves about what constitutes the good life, and what we’re willing to trade to get it. With cars, at least, we might have the seeds of a different story. Dethroning the automobile in car-loving America remains a grueling, uphill battle, and I wouldn’t necessarily call myself optimistic, but transportation reform flows quite naturally from the changes we already know we need to make to solve our housing shortage. The best way to reduce the number of miles we drive is to permit a greater density of homes anywhere where there’s demand for it, especially in the parts of cities that already have the affordances of car-free or car-light life (and it’s definitely not all or nothing — I own a car and can appreciate its conveniences, while driving maybe a quarter as much as the average American). The housing abundance movement is winning the intellectual argument necessary to change policy in that direction. And maybe most crucially, we know many Americans want to live in these places — some of the most in-demand homes in the country are in walkable neighborhoods. If we make it easy to build lots of housing in the centers of growing cities, people will move there. But animal agriculture, barring a game-changing breakthrough in cell-cultivated meat, is a somewhat different story. It’s one thing to show that we’re not missing out on economic growth by forgoing meat, and quite another to persuade people that eating less of it isn’t a sacrifice — something the plant-based movement hasn’t yet figured out how to do. At bare minimum, we ought to be pouring public money into meat alternatives research. There’s no shortage of clever policy ideas to nudge consumer choices in the right direction — but for them to succeed rather than backfire terribly, people have to want it. And to that end, I’d encourage anyone to discover the abundance of a low- or no-meat diet, which is an easier choice to make in most of America than escaping car dependence. Right now, our livestock and our automotive herd squander the resources that could be used to make industrial modernity sustainable for everyone. We grow less than we might because we waste so much on cars and meat. Reclaiming even a fraction of that capacity would make the math of decoupling less brutal, freeing us to build whatever else we can imagine. There’s no guarantee we’ll make that choice, or make it in time — but the choice is ours. This series was supported by a grant from Arnold Ventures. Vox had full discretion over the content of this reporting.

The first thing that struck me about this year’s most talked-about policy book, Abundance (perhaps you’ve heard of it?), is a detail almost no one talks about. The book’s cover art sketches a future where half of our planet is densely woven with the homes, clean energy, and other technologies required to fill every human […]

The first thing that struck me about this year’s most talked-about policy book, Abundance (perhaps you’ve heard of it?), is a detail almost no one talks about.

The book’s cover art sketches a future where half of our planet is densely woven with the homes, clean energy, and other technologies required to fill every human need, liberating the other half to flourish as a preserve for the biosphere on which we all depend — wild animals, forests, contiguous stretches of wilderness.

It’s a beautiful ecomodernist image, suggesting that protecting what we might crudely call “nature” is an equal part of what it means to be prosperous, and that doing so is compatible with continued economic growth. It’s a visual rebuke to those who argue that we must choose between the two.

How would we do it?

The US and its peer countries today are spectacularly rich — unimaginably so, from the vantage of nearly any point in human history — and it might be tempting to think that we have grown enough, that our environmental crisis is so grave that we should save our planet by shrinking our economy and freeing ourselves from useless junk. I understand the pull of that vision — but it’s one that I think is illusory and politically calamitous, not to mention at odds with human freedom. A world where economic growth goes into reverse is a world that would see ever more brutal fighting over shrinking wealth, and it is far from guaranteed to benefit the planet.

Yet that doesn’t change the essential problem: Climate change and the destruction of the natural world pose grave immediate threats to humans, and to the nonhuman life that is valuable in itself. And we are not on track to manage it.

It’s not easy to reconcile these realities, but it is possible and necessary to do so in a way that’s consistent with liberal democratic principles. Instead of deliberately shrinking national income, we can seek out the areas of greatest inefficiency in our economy and chart a path that gets the most economic gain for the least environmental harm. If growing the economy without torching the planet is feasible in principle — and I think it is — then we should fight for it to grow in the best direction possible.

Inside this story

• Meat and dairy, plus our extreme dependence on cars, are two huge efficiency sinks: they produce a big share of emissions and devour land, and they aren’t essential to economic growth or human flourishing.

• Shifting diets toward plant-based foods and freeing up land could act like a giant carbon-capture project, buying time to decarbonize.

• Reducing car dependence would slash transport emissions, make land use more efficient, and make Americans healthier and safer — without sacrificing prosperity.

We’ll need to build out renewables at breakneck speed and electrify everything we can, of course. But some of the most powerful levers we have to decouple economic growth from environmental impact challenge us to do something even harder — to begin outgrowing two central fixtures of American life that are as taken-for-granted as they are supremely inefficient: our extreme dependence on meat and cars.

Changing those realities is so culturally and politically heretical in America that this case is almost never made in climate politics, but it deserves to be made nonetheless. And doing so will require examining the trade-offs that we too often treat as defaults.

Two great efficiency sinks

It’s probably not news to you that cars and animal-based foods are bad for the planet — together they contribute around a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions both globally and within the US. Animal agriculture also devours more than a third of habitable land globally (a crucially important part of our planetary crisis) and 40 percent of land in the lower 48 US states, while car-dependent sprawl fragments and eats into what’s left at the urban fringe.

We obviously need food and transportation, but meat and cars convert our planet’s resources into those necessities much more wastefully than the alternatives: plant-based food, walking, public transportation, and so on. And in a climate-constrained economy that still needs to grow, we don’t have room to waste. Beef emits roughly 70 times more greenhouse gases per calorie than beans and 31 times more than tofu; poultry emits 10 times more than beans and four to five times more than tofu. Mile-for-mile, traveling by rail transit in the US emits about a third as much as driving on average, while walking doesn’t emit anything.

For all that resource use, animal agriculture and autos are not indispensable to our economy or to our continued economic growth.

The entire US agricultural sector, plus the manufacture and servicing of automobiles, make up a tiny share of our GDP; like other advanced economies, America’s is largely service-based, employing workers in everything from health care to law firms to restaurants and retailers like Amazon and Walmart. Of course, agriculture, energy, and manufacturing are foundational to everything else in the economy — without farming, Chipotle and Trader Joe’s would have no food to sell, and more importantly, we would starve. To say that agriculture isn’t a major part of our economy isn’t to say that it’s not really important to having an economy.

But it is, unsurprisingly, those foundational parts of the economy that disproportionately drive resource use and environmental impact — and because they’re a small share of the economy, we have a lot of room to change their composition without crashing GDP.

If we shifted a chunk of our food production away from meat and dairy and toward plant-based foods, for example, the already economically tiny ag sector might shrink somewhat. Meanwhile, we would save a lot of greenhouse gas emissions and land, and it would be reasonable to infer that the food service and retail sectors, which make up a significantly larger share of US GDP than agriculture does, would function all the same because we’d still eat the same number of calories and buy the same amount of food. With less meat consumption, the US might even have a significantly bigger alternative protein sector, with cleaner, better jobs than farm or slaughterhouse work.

Which is not to say there wouldn’t be any losers in the short run — job losses and stranded capital in industries that are regionally concentrated and politically powerful. But those transitions can be managed, just as we have been managing the transition away from fossil fuels.

This is exactly what decoupling — the idea that we can grow richer while decreasing emissions and other environmental impacts — looks like. The US, like a lot of other developed countries, has largely managed that in carbon emissions from energy consumption, which have fallen around 20 percent since 2005, even as the economy has grown about 50 percent in real terms. Agriculture has become more efficient, too, but it still lags on decoupling; the sector’s emissions are mostly flat or rising. Road transport tells a similar story: cars and trucks have gotten more efficient, but total emissions from driving are still stuck near their mid-2000s levels.

Admittedly, it’s easier to decouple for energy than it is to change the way we eat or move around. A megawatt is a megawatt, whether it’s produced by coal or solar, while switching from steak to beans is not the same experience. But learning how to use resources more efficiently is, after all, a big part of how wealthy nations have become wealthy, including in these tougher sectors. Despite how inefficient our food system still is, the US has managed to significantly decrease how much land it uses for farming over the last century, while producing much more food. We could go much further if we weren’t so reliant on eating animals.

Now, you might be thinking, so what if American GDP doesn’t depend on meat and cars? People like them, and they’re part of what it means to be rich and comfortable in the modern world. And you would have a point. No one would say that heating and cooling shouldn’t exist (well, the French might) just because they use a lot of energy and make up a tiny share of the economy.

But every choice we make in the economy is a trade-off against something else, and everything we spend our limited carbon budget on is a choice to forgo something else. Our task is to decide whether high meat intake and extreme car dependence are worth that trade — whether they make up for their toll on the planet in contributions to our economy or to our flourishing as human beings.

The “eating-the-Earth” problem

We can start with animal agriculture, because however bad for the planet it looks on first impression, it’s actually worse.

Estimates of the livestock industry’s greenhouse gas emissions range from around 12 to 20 percent globally; in the US, it’s around 7 percent (despite the lower percentage, per capita meat consumption is substantially higher in the US than it is globally — it’s just that our other sources of emissions are even higher). But those numbers don’t account for what climate scientists call the carbon opportunity cost of animal agriculture’s land use.

This story was first featured in the Processing Meat newsletter

Sign up here for Future Perfect’s biweekly newsletter from Marina Bolotnikova and Kenny Torrella, exploring how the meat and dairy industries shape our health, politics, culture, environment, and more.

Have questions or comments on this newsletter? Email us at futureperfect@vox.com!

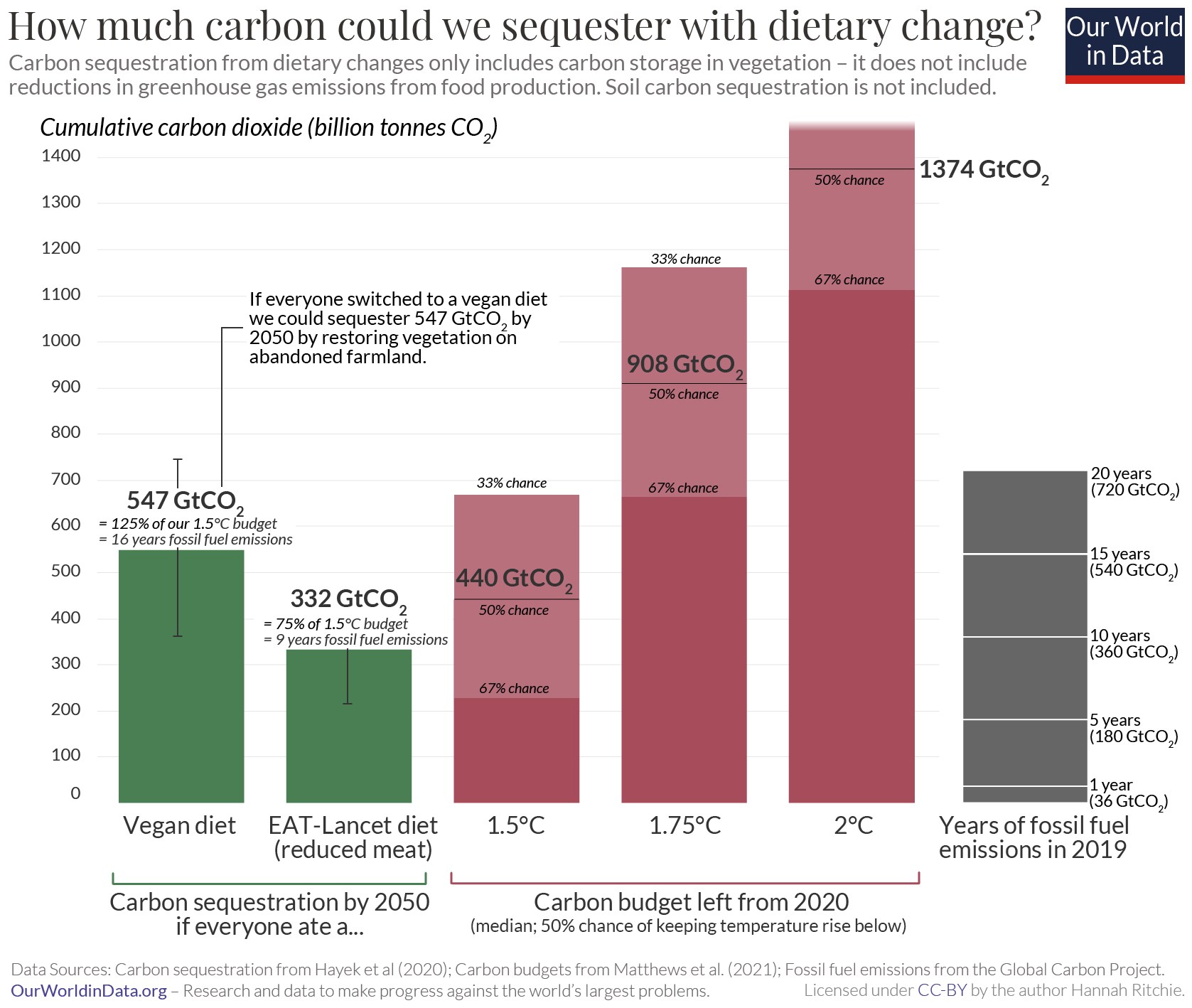

Recall that farming animals for food takes up a massive amount of land, because we need space for the animals and for the crops needed to feed them. Meat and dairy production hogs 80 percent of all agricultural land to produce what amounts to 17 percent of global calories. Much of it could instead be rewilded with climate-stabilizing ecosystems, which would support biodiversity and also happen to be among our best defenses against global warming because of how good they are at sequestering carbon.

How big would the impact be? The canonical paper on the carbon opportunity cost of animal agriculture finds that a 70 percent reduction in global meat consumption, relative to projected consumption levels in 2050, would remove the equivalent of about nine years of carbon emissions, while a global plant-based diet would remove 16 years of emissions; another study concludes that a rapid phaseout of animal agriculture could effectively freeze increases in all greenhouse gases over the next 30 years, and offset most carbon emissions this century.

It’s worth pausing to appreciate just how miraculous that is. Freeing up even some of the land now used for meat and dairy turns it into a negative-emissions machine better than any existing carbon capture technology, giving us a carbon budget windfall that could ease the phaseout of fossil fuels and buy time for solving harder problems like decarbonizing aviation. This is as close as it gets to a free lunch, as long as you’re willing to make it a vegan lunch.

Organizing society around cars doesn’t make sense

We can think of car dependence as the other big resource black hole in US society.

Transportation is the top source of greenhouse gas emissions in the country, and cars are the biggest source within that category, accounting for about 16 percent of all US emissions. Globally, gas-powered cars are in retreat — a very good thing for both climate change and deadly air pollution, though the US is increasingly falling behind peer countries in auto electrification.

Still, if it were just a matter of swapping out gas-guzzlers for EVs, auto transportation wouldn’t be an obstacle to truly sustainable growth. But EVs alone aren’t a silver bullet for repairing the environmental problems of cars.

One influential paper on the subject found as much in 2020, concluding that, at any realistic pace of electrification, EV growth wouldn’t be enough to meet climate targets, and even with universal adoption, EVs aren’t emissions-free. They take lots of energy to make — especially those heavy batteries — and an enormous amount of steel and critical minerals. These are scarce inputs that we also need to decarbonize the electric grid and build other green infrastructure.

That isn’t to say that EVs aren’t better for the climate than gas-powered vehicles — they absolutely are. But as the lead author of that paper wrote in an accompanying commentary, “The real question is, do you even need a car?”

The problem is not the existence of cars, but our total dependence on them. In most of the country, Americans have no other convenient transportation options. And remember, we’re trying to optimize for the least resources used for the most economic upside. Organizing society around the movement of hundreds of millions of two-ton metal boxes is… obviously not that, and the reasons why go well beyond emissions from the cars themselves. The car-dependent urban form that dominates America forces us to build things spread far apart — sprawl, in other words — which forces us to use more land. As of 2010, according to one estimate, the US devoted a land area about the size of New Jersey to parking spots alone.

Our cities and suburbs occupy less than one-tenth as much land as farming — about 3 percent of the US total — but they still matter for the environment, fragmenting the habitats on which wildlife and ecosystems depend. Plus, housing in the US is sprawling enough that some exurban communities stretch across outlying rural counties, occupying an unknown additional share of land that’s not included in the 3 percent figure.

Perhaps most damaging from an economic perspective, the sprawling development pattern that car dependence both enables and relies upon has driven the misallocation of valuable land toward low-density single-family homes, driving our national housing crisis. Cars are by no means the sole reason behind the housing shortage, but without mass car dependence, it would be vastly harder to lock so much of our land into inefficient uses. Meanwhile, Americans pay dearly for car dependence in the form of costly infrastructure and tens of thousands of traffic deaths each year.

Urbanists sometimes like to say that the US prioritizes cars over people — that an alien arriving on Earth would probably think cars are our planet’s apex species. In some senses, that’s certainly true — the privileges that we’ve reserved for cars make it harder to meet the basic human need of housing, which makes us poorer and diminishes the agglomeration effects that make cities dynamic and productive. One widely cited paper estimated, astonishingly, that housing supply constraints, especially in the highest-productivity cities, cut US economic growth by 36 percent, relative to what it would have been otherwise, from 1964 to 2009. Imagine how much higher the GDP of Los Angeles would be if it doubled its housing stock and population and, with its freeways already maxed out, enabled millions more people to get around on foot, bike, and transit.

And, of course, since autos and animal products are both very high in negative externalities, the benefits of reducing our collective dependence on them go well beyond the strictly economic or environmental. Americans would spend less money managing chronic disease and die fewer premature deaths (in the case of meat and dairy, probably, and in the case of cars, undoubtedly). We would torture and kill fewer animals (and fewer people would have to spend their working lives doing the killing). We would help keep antibiotics working, and we might even prevent the next pandemic.

But will we do it?

The growth that brought us industrial modernity is an awe-inspiring thing: It’s given us an abundance of choices, and it’s made obsolete brutal ways of life that not long ago were a shorthand for prosperity, like coal mining or the hunting of whales to make industrial products. Prosperity can be measured concretely in rising incomes and lengthening lifespans, but it’s also an evolving story we tell ourselves about what constitutes the good life, and what we’re willing to trade to get it.

With cars, at least, we might have the seeds of a different story. Dethroning the automobile in car-loving America remains a grueling, uphill battle, and I wouldn’t necessarily call myself optimistic, but transportation reform flows quite naturally from the changes we already know we need to make to solve our housing shortage.

The best way to reduce the number of miles we drive is to permit a greater density of homes anywhere where there’s demand for it, especially in the parts of cities that already have the affordances of car-free or car-light life (and it’s definitely not all or nothing — I own a car and can appreciate its conveniences, while driving maybe a quarter as much as the average American). The housing abundance movement is winning the intellectual argument necessary to change policy in that direction. And maybe most crucially, we know many Americans want to live in these places — some of the most in-demand homes in the country are in walkable neighborhoods. If we make it easy to build lots of housing in the centers of growing cities, people will move there.

But animal agriculture, barring a game-changing breakthrough in cell-cultivated meat, is a somewhat different story. It’s one thing to show that we’re not missing out on economic growth by forgoing meat, and quite another to persuade people that eating less of it isn’t a sacrifice — something the plant-based movement hasn’t yet figured out how to do. At bare minimum, we ought to be pouring public money into meat alternatives research. There’s no shortage of clever policy ideas to nudge consumer choices in the right direction — but for them to succeed rather than backfire terribly, people have to want it. And to that end, I’d encourage anyone to discover the abundance of a low- or no-meat diet, which is an easier choice to make in most of America than escaping car dependence.

Right now, our livestock and our automotive herd squander the resources that could be used to make industrial modernity sustainable for everyone. We grow less than we might because we waste so much on cars and meat. Reclaiming even a fraction of that capacity would make the math of decoupling less brutal, freeing us to build whatever else we can imagine. There’s no guarantee we’ll make that choice, or make it in time — but the choice is ours.

This series was supported by a grant from Arnold Ventures. Vox had full discretion over the content of this reporting.