Underwater Forests Return to Life off the Coast of California, and That Might be Good News for the Entire Planet

Underwater Forests Return to Life off the Coast of California, and That Might be Good News for the Entire Planet Wondrous kelp beds harbor a complex ecosystem that’s teeming with life, cleaning the water and the atmosphere, and bringing new hope for the future The Palos Verdes Kelp Forest Restoration Project near Los Angeles forms an ecosystem that is home to many creatures. Sage Ono Every year, on a late summer night, Eva Pagaling joins a group of fellow Chumash paddlers who climb into a tomol, a handcrafted wood-plank canoe, for an eight-to-ten-hour voyage from the California mainland. They head for the largest of the Channel Islands, an archipelago sometimes called the Galápagos of North America due to its stunning biodiversity. The island appears on maps as Santa Cruz; the Chumash call it Limuw. Pagaling, who is now 35, has been taking part in the annual journey since she was 10. As the youngest daughter of a master canoe builder, she grew up hearing oral histories and learning songs about her Indigenous group, among the first people to inhabit the California coast at least 13,000 years ago, but she emphasized that this annual tradition is more than ceremonial. “This isn’t a replica of a tomol,” she said. “We aren’t just descendants of the Chumash; this isn’t just a re-enactment of our journey. This is who we are and what we are doing right now.” But one thing that has changed over the generations is the condition of the channel waters. For millennia, the Chumash and other Indigenous people sustained themselves in part by spear hunting in kelp forests teeming with fish. “We still catch halibut, tuna and rockfish,” said Pagaling, who is a Chumash tribal marine consultant as well as a trained rescue diver. “But these marine ecosystems are not as healthy as when our ancestors were eating the fish.” Pagaling is the board president of the nonprofit Ocean Origins, and she collaborates with marine scientists to restore one of the planet’s most precious resources: the kelp forests that once grew thick and wide in tidal corridors up and down the Pacific Coast. Eva Pagaling, board president of the nonprofit Ocean Origins. Pagaling belongs to the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. The Chumash have spent many thousands of years living on California’s central coast and outer Channel Islands, paddling in a canoe called a tomol. Sage Ono Kelp forests keep ocean waters clean and oxygenated while hosting a wide variety of fish and sea life. These green and amber stalks of aquatic vegetation, which grow up to 175 feet from the seafloor to the surface, not only combat pollution but also mitigate climate change. Kelp forests absorb carbon dioxide from both the air and water that would otherwise linger for centuries. They can absorb 20 times more CO2 compared with same-size terrestrial forests. In the 1830s, Charles Darwin was amazed by the kelp ecosystems he found flourishing in the Pacific waters around the Galápagos. “I can only compare these great aquatic forests ... with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions,” he wrote in his journal. “Yet, if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish as would here, from the destruction of the kelp.” Kelp is an umbrella term for 30 types of algae that grow along nearly a third of the world’s coastlines—in Maine and Long Island, in the United Kingdom and Norway, in Tasmania and southern Africa, in Argentina and Japan. With a global coverage of more than two million square miles, kelp takes up roughly the same space as the Amazon rainforest. But few places in recorded history have had more abundant kelp forests than the 840 miles along California’s coastline. Over the past few hundred years, that changed. First came the 18th-century fur traders, who trapped the sea otters of Monterey Bay, natural predators of the purple urchins that feast on kelp stalks, stems and blades. By the early 20th century, otter populations were hunted to near extinction. Kelp beds were consumed until they turned into desolate underwater areas known as urchin barrens. Fish populations disappeared with the kelp. Fun Fact: What is kelp, anyway? Kelp isn’t a plant. It’s a very large type of algae that can grow to be 150 feet tall. Gas-filled compartments allow kelp blades to float upright. Tangled extensions keep them anchored to the seafloor. Co-founders of Ocean Origins include, from right, project scientist Jesse Altemus, director of science Selena Smith and cultural adviser Josh Cocker (who is Eva Pagaling’s husband). Sage Ono Then came the rise of the automobile. In 1921, California created the world’s first tidelands oil and gas leasing program, attracting energy producers that drilled hundreds of offshore oil wells across the Santa Barbara Channel. Oil platforms rose up from the sea. Oil leaks became common, along with the bubbling up of ocean floor tars. On January 28, 1969, one of the Union Oil Company’s main offshore platforms had a blowout, the largest in U.S. history at the time. As many as 4.2 million gallons of crude oil poured into the sea, killing thousands of seabirds, seals and sea lions, and also destroying the kelp forests. The drilling didn’t stop, but mass protests and the burgeoning environmental movement pushed the federal government to set aside certain tidal waters as nature reserves. In 1980, the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary began protecting endangered species and sensitive habitats in nearly 1,500 square miles of ocean waters around the five northern Channel Islands. Yet the channel waters by Santa Barbara’s mainland remained open to drilling and industrial uses. In recent years, the most destructive culprit has been climate change. From 2013 to 2016, the entire Pacific coast was hit with unprecedented El Niño events, when differentials in global winds and air temperatures set off superstorms. In 2015 alone, 16 tropical cyclones roiled the central Pacific hurricane basin, with rising water temperatures whacking kelp ecosystems out of balance. Nick Bond, climatologist for the state of Washington, called this marine heat wave “The Blob,” after the 1958 B-movie. Some kelp beds lingered in remnants, while others disappeared almost entirely, replaced by piles of purple urchins. “It’s like seeing a forest that’s been clear-cut,” said marine conservationist Norah Eddy, the associate director of oceans programs for the Nature Conservancy in California. “It’s that shocking.” In 2015, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council submitted a nomination to the federal government for its own marine protected area. In November 2024, it became official. The Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary now begins at the tip of the Channel Islands and stretches north over 116 miles of shore, more than 13 percent of California’s coastline. More than 4,500 square miles of tidal waters are now protected from offshore oil drilling, pollution, industrial development, overfishing and habitat destruction. I wanted to see a healthy kelp forest for myself. On a chilly December morning, right after sunrise, I arrived at Ventura Harbor to board a dive boat for an all-day excursion with a couple dozen other kelp forest explorers. My scuba skills were rusty, so I opted to snorkel, renting gear and a wet suit. Charles Darwin Public Domain / Wikipedia On board was Selena Smith, a marine biologist who co-founded Ocean Origins along with Pagaling and two others. Smith also served as director of education at the Reef Check Foundation, a global organization that documents both coral reefs and kelp forests. On the choppy, two-hour outbound boat ride, Smith told me about how advanced ecological modeling, genetic studies of kelp and underwater mapping are being deployed for restoration projects. By learning how and why the algae thrive under certain conditions, Ocean Origins aims to restore kelp in many locations. Its team members regularly find plastic and other trash stuck in the blades. “Mylar balloons are horrible,” Smith said. “They are definitely harmful to the marine environment and its occupants.” The boat dropped anchor in a spot so close to the ancient volcanic rock of Limuw that we could almost peer into the sea caves that line its shores. The surface of the water was teeming with kelp, so it looked like we had come to the right place. I took a ladder down to a small platform and let myself fall backward into the sea. The 55-degree water was perfect for kelp growth, and magnificent visibility offered pristine views of the underwater forest. I swam toward the stalks until I found myself inside amber cathedrals of giant kelp, a robust species native to Southern California. A group of whiskered sea lions came out to greet us. With bodies twice as long as otters’, and leathery skin rather than fur, the lions police these places, feasting on fish to maintain their weight. For males, that can be upwards of 700 pounds. The kelp reefs were a riot of color—populated with emerald, navy and ginger fish; spindly lobsters with bright yellow eyes; golden sea stars; anemones with magenta tentacles that gave a turquoise glow; and kelp shaped like olive feather boas and butterscotch bulbs. More than a thousand documented species of plants and animals can be found here. Drawing many gazes from the divers were the nudibranchs—sea slugs that appeared in vibrant blue and orange. This ecosystem was thriving for one main reason: It had been cleaned up and then left alone. “Areas that are protected from fishing tend to have higher amounts of kelp, creating a better environment and generating more diversity,” Smith said. “This past year has been an especially good one.” Over the decades, there have been several notable stories of successful kelp revival. In the waters near Monterey, scientists and enthusiasts boat out weekly to dive into and monitor the aquatic forests. Ever since 1984, the Monterey Bay Aquarium has been helping protect the local waters from pollution and industrial development. The Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, established in 1992, expanded the effort, and now some 3,000 sea otters thrive between Half Moon Bay near San Francisco and Point Conception near Santa Barbara. The kelp’s ebbs and flows depend mostly on water temperature. Off the coast of Palos Verdes, a famed surfing spot 30 miles south of Los Angeles, marine biologist Tom Ford, CEO of the Bay Foundation, operates one of the world’s most impressive kelp restoration projects. After moving to the area in 1998, Ford went out scuba diving and encountered a kelp forest. “That was it,” he said. “I was hooked.” For his master’s degree at the University of California, Los Angeles, Ford studied the trajectories of loss and recovery of kelp all over the world, and the many creatures that depended on it. “If it’s gone,” he said, “they’re essentially homeless.” Urchin remains pile up in the water near Palos Verdes after the spiny creatures—relatives of sea stars and sand dollars—ran out of kelp to eat. Sage Ono By 2013, Ford was ready to start work with a group of student volunteers, but he had barely gotten going when the coast was hit by The Blob. “We stopped restoration work,” he said. What they found were ailing purple echinoderms as far as the eye could see. They had consumed all the kelp, and now they were starving. “Their spines covered entire ocean floors like marble tile,” Ford told me. He and his team dove into the water and smashed urchins to death with hammers, which released nutrients that would nourish other marine creatures. It’s taken a decade of relentless work to clean out enough urchins and replenish the area. “We restarted this ecological machine so it could restore its own health,” Ford said. By 2024, a 70-acre forest, the size of about 53 football fields, became the biggest kelp restoration success story in the United States. A year later, when I rode on the dive boat with Ford and his crew, the restoration area had grown to 80 acres, or around 60 football fields. We swam in the aftermath of a summer heat wave, with the water’s surface at a toasty 72 degrees. The heat was causing some of the kelp blades to disintegrate, clouding the waters. But Ford showed me how the same ocean bottom that once looked pale and dead was now covered in kelp stalks and green, red and brown algae. Healthy urchins were present in small numbers. Ford’s studies show that having fewer than three urchins per ten square feet keeps the ecosystem in balance. Yet he acknowledged that clearing out urchins by hand takes too long. He told me he’s looking forward to new tools and techniques that could make restoration easier and more productive. When it comes to the economy and the planet, cultivating kelp is a worthwhile venture. Perhaps the most promising business model is an outfit called Ocean Rainforest, which had success growing sugar kelp in the Faroe Islands of the North Atlantic Ocean and chose the Santa Barbara Channel as its next locale. Its 86-acre giant kelp farm, created from scratch four miles offshore, grows kelp on ropes that are attached to buoys. The buoys have GPS devices on them, and the team does biweekly monitoring, taking measurements of water temperature, nutrients and salinity. “The entire farm is engineered as one unit,” Douglas Bush, the director of California operations for Ocean Rainforest, said. Base Map: Copyright © Free Vector Maps.com On a visit to his land-based facility in Goleta, California, Bush showed me giant metal vats that process the kelp into a liquid biostimulant for agriculture. By spraying this natural compound on soil, farmers hope to reduce the need for artificial fertilizers that give off nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas that traps 300 times as much heat per pound as CO2. The kelp-based product may boost yields and reduce the water needed for cash crops ranging from almonds and avocados to strawberries and grapes. (“Those are benefits attributed to seaweed biostimulants in general,” Bush noted carefully. “Our hope is to evaluate those claims in trials using our product.”) Because California farms produce nearly half of America’s vegetables and three-quarters of its fruit and nuts, improving local agricultural techniques is no small achievement. “The reason we’re here is to be part of the solution, to improve regional food systems, to be a creative tool in the toolkit for regenerative agriculture,” Bush said. By cultivating kelp, he hopes to help meet the growing demand for seaweed products without putting strain on existing wild kelp forests. Brian von Herzen, a planetary scientist who is the founder and executive director of the Climate Foundation—a nonprofit founded in California—believes that using kelp as a biostimulant for agriculture is a gigantic financial opportunity. “Furthermore, the seaweed forests play key roles in natural climate repair, which is essential at this late stage in our climate journey,” he said. Von Herzen and his team invented growing lattices with electric motors that lower seaweeds each night to absorb nutrients, and raise them up to the surface each morning to catch full sunlight and absorb carbon dioxide in the top few feet of the sea. This enables growth in areas that don’t have enough natural upwelling, due to warming waters. The foundation has a kelp farm in Philippines waters, where it sells a kelp-based fertilizer called BIGgrow. Terry Herzik usually earns his living fishing for urchins, a culinary delicacy. Here, he smashes them instead to help restore Palos Verdes’ kelp forests. Sage Ono In 2023, von Herzen’s group began hosting marine permaculture workshops in California to raise awareness. The group now collaborates with Ocean Origins, as well as with scientists at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Removing CO2 from the air is expensive with methods like direct-air capture machines, driven by giant fans. Each ton of carbon can cost as much as $1,000 to capture. Von Herzen estimates that kelp can remove CO2 at a cost of just $20 to $85 per ton, without requiring any machinery. A single acre of kelp forest can take in 16 tons, von Herzen said, “but our arrays can do more than double that, 35 tons of CO2 per acre per year,” or about the annual emissions of six gasoline cars. Existing global seaweed forests can capture nearly 200 million tons of CO2 a year while also giving a $500 billion boost in ecosystem services to industries including fishing. Expanding them is an excellent investment, said von Herzen, both financially and environmentally. And using biostimulants can boost the climate benefit even more, both by reducing nitrous oxide emissions and by cutting the CO2 emissions that come both from making artificial fertilizers and from shipping them to farmers. California is already outpacing the rest of the country in reducing fossil fuel emissions. Kelp would help the state meet its target of reaching net-zero emissions by 2045, at least five years sooner than the Paris Agreement’s goal of 2050. Seaweeds currently grow across nearly 1 percent of the world’s temperate coastal ocean waters. Getting back to pre-industrial levels of about 2 percent would be revolutionary. Von Herzen is focusing on specific species, which grow three times faster than other kelp. He said they could remove enough carbon to equal all emissions from global aviation—all flights using jet fuels everywhere in the world. What’s more, studies show that kelp forests give off biogenic aerosols—tiny airborne particles that come from living things—that help clouds form. Coastal cloud cover reflects sunlight back into space. In its absence, the seas and soils are hotter, which also heats the air. There is more evaporation, and there are longer periods without rain. The ground becomes drier, making coastal woodlands more susceptible to wildfire. “We can keep California cooler and keep it from burning,” von Herzen said. “This can be done not in the distant future, but within the next ten years.” That’s because kelp can expand its coverage by 18 inches per day. Some giant kelp grow at a daily rate of two feet. To take in the full glory of kelp, I flew to a set of seaside towns near Eureka, roughly 100 miles south of the Oregon border, that were playing host to the California Seaweed Festival, a two- or three-day event that pops up each year in different parts of the state. The festival, now in its sixth year, was co-founded by biologist Janet Kübler, who spelled out the challenges and opportunities for kelp in a 2021 paper in the Journal of the World Aquaculture Society. “It’s not just a conference,” Kübler told me. “It’s a celebration of seaweed, not just as a food or a carbon sink, but all of its possibilities.” This article is a selection from the December 2025 issue of Smithsonian magazine At the Palos Verdes Kelp Forest Restoration Project, a school of bright blue blacksmith fish swims through healthy green blades of giant kelp and red algae. Sage Ono Inside the festival’s main venue at Eureka’s Wharfinger Building, a diverse set of scientists, including Indigenous leaders, was ready to point to their wall posters and chat about their research. Leaders of the Sunflower Star Lab were on hand to talk about recovery from The Blob, which brought about sea star wasting syndrome, all but killing off this keystone species, another natural predator of purple urchins. The stars, which stood in small tanks on display here, grow up to 39 inches wide. When they are released near a kelp forest, a slow-motion chase scene ensues. Urchins sense danger from chemicals released by the stars and try to escape. But the stars are speedier. Finally, a star will clutch and consume an urchin. Outside, a bluegrass band called the Compost Mountain Boys played as attendees toured the farmer’s market. A stand operated by Sunken Seaweed, a startup that skyrocketed out of San Diego, drew much of the attention. The table was staffed by its co-founder Torre Polizzi, who sold me a $12 jar of Califurikake, a local twist on Japanese-style seasoning made from seaweed. The festival underscored the versatility of this underappreciated climate solution. I was familiar with kelp-based protein smoothies for humans, but I learned how sprinkling seaweed on cattle feed can help cows digest their food, reducing their methane emissions between 40 and 80 percent. Kelp can also serve as an ingredient in biodegradable biopolymers, which are used in place of petroleum-based plastics. In 2020, a nonprofit called the Lonely Whale Foundation announced a $1.2 million Plastic Innovation Prize in partnership with Tom Ford Beauty (a company founded by fashion designer Tom Ford, not by marine biologist Tom Ford who runs the Bay Foundation). The top award, announced in 2023, went to a California company called Sway, which makes a seaweed-based alternative to thin-film plastic packaging. At the docks, I boarded a boat for a Humboldt Bay harbor cruise. Out on the sparkling water, we spotted pelicans gliding in for a lunch of fish. The boat passed an aquatic farm established in 2020 that had produced more than 3,000 pounds of bull kelp that year. On the cruise, a Los Angeles company called Blue Robotics was showing images captured by a remotely operated vehicle that can help tend kelp several hundred feet underwater. At night, a party billed as the Seaweed Speakeasy featured local beers made with kelp instead of malt, served along with seaweedy hors d’oeuvres. I found a station serving mac and kelp and cheese that went down easy with the beer. Jasmine Iniguez, an aquaculturalist at College of the Redwoods in Northern California, pulls a line of seaweed out of the water as she helps haul up the kelp harvest. Sage Ono The festival culminated at the marine lab of Cal Poly Humboldt. Pulling on latex gloves, I stood beside a lab table set with fresh ribbons of kelp and learned how to assess its reproductive health by isolating the tissue that holds its spores. With a razor, I scraped a slimy layer off a blade, splashed it with iodine and set the substance under a microscope. The batch held spores with excellent motility (the ability to move well on their own). Each spore grows into a microscopic organism, either male or female. The males will release sperm into the water, and the females will release chemicals that help the sperm find their eggs. I left the festival feeling satisfied and, dare I say, optimistic, yet with some big unresolved questions. Where was this kelp work heading? How big could the movement really get? What kinds of signs would urge people to take such solutions seriously? The last of these questions took on even more urgency for me in January, after winds up to 100 miles an hour hit Los Angeles, where I live. The gusts stoked flames on parched lands, creating Southern California’s most devastating winter fire in decades. The result: death, devastation and more than $75 billion in damages. Three California spiny lobsters at the Palos Verdes Kelp Forest Restoration Project. The lobsters prey on sea urchins, which helps kelp to thrive. Sage Ono The average person may know the Earth is warmer now than at any time in the past 100,000 years, or that each year now sets a global temperature record. But what happens underwater is so rarely seen. Most people have no idea that seaweeds have been around for a billion years, or that algae and aquatic plants provide the planet with about half of its oxygen, the other half coming from terrestrial plants. Most people don’t know that ocean water has already absorbed about a third of humanity’s excess carbon emissions, and that the resulting carbonic acid disrupts the ocean’s chemistry, leaving less calcium for the hard shell casings of shellfish—or that cultivating kelp serves as a giant pushback against this process. Most people don’t know that seaweeds can be used to make natural, low-cost alternatives to plastics and fertilizers. At Ocean Rainforest, solid kelp is ground into a slurry and then transformed into a biostimulant that can reduce farmers’ reliance on synthetic fertilizers. The strawberry plant shown above is in a container that was made partly from kelp. Sage Ono The Chumash people know all of this. I met Pagaling at Goleta Beach, near Santa Barbara, to chat on a bench by the playground, where her 4-year-old was having a wonderful time. Pagaling pointed to seaweed that had washed ashore on the sand and described how the Chumash had been gathering the stuff from beaches for centuries. She uses it as a fertilizer for her family’s garden of corn, squash, beans, carrots and zucchini. “You can watch the plants really take off,” she said. Seaweed-based products line shelves at North Coast Co-op in Eureka. The company’s founders are helping to rebuild kelp forests. Sage Ono As we gazed out at the ocean, she lamented the loss. “That’s where our food was provided, our staple areas, our swimming and fishing,” she said. Then came the pollution, the overfishing, the poor land and water management practices. Oil platforms are still visible to anyone driving north from Los Angeles along Highway 101. After a century of drilling, Californians have now spent more than a decade taking steps toward decommissioning the rigs. Still, as intrusive as the rigs once were, ecosystems have adapted around them. As with shipwrecks, the rigs are now habitats for arrays of marine life. That’s how resilient nature can be. Even many staunch environmentalists agree that the underwater structures should remain after they’re no longer in use. A healthy habitat at Palos Verdes. Instead of roots, kelp has a tangle of extensions called a holdfast that keeps it anchored it to the seafloor. Sage Ono Pagaling spoke of the celebrations on the Chumash reservation when the federal government approved the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary and the outlook for leading restoration of nature along the coast. “There are so many kelp forest opportunities now,” she said. “It will take collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups.” Yet she acknowledged that there have been few collaborations like this before. “Lots of communities say they are for restoration, but there is often disagreement over how.” When the tomol crew reaches Limuw, a crowd of people from the Chumash community and beyond will welcome those who paddled all through the night. Next year, Pagaling says, the gathering won’t only be about honoring the past. It will also celebrate the possibility of a better future. Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Wondrous kelp beds harbor a complex ecosystem that’s teeming with life, cleaning the water and the atmosphere, and bringing new hope for the future

Underwater Forests Return to Life off the Coast of California, and That Might be Good News for the Entire Planet

Wondrous kelp beds harbor a complex ecosystem that’s teeming with life, cleaning the water and the atmosphere, and bringing new hope for the future

Every year, on a late summer night, Eva Pagaling joins a group of fellow Chumash paddlers who climb into a tomol, a handcrafted wood-plank canoe, for an eight-to-ten-hour voyage from the California mainland. They head for the largest of the Channel Islands, an archipelago sometimes called the Galápagos of North America due to its stunning biodiversity. The island appears on maps as Santa Cruz; the Chumash call it Limuw.

Pagaling, who is now 35, has been taking part in the annual journey since she was 10. As the youngest daughter of a master canoe builder, she grew up hearing oral histories and learning songs about her Indigenous group, among the first people to inhabit the California coast at least 13,000 years ago, but she emphasized that this annual tradition is more than ceremonial. “This isn’t a replica of a tomol,” she said. “We aren’t just descendants of the Chumash; this isn’t just a re-enactment of our journey. This is who we are and what we are doing right now.”

But one thing that has changed over the generations is the condition of the channel waters. For millennia, the Chumash and other Indigenous people sustained themselves in part by spear hunting in kelp forests teeming with fish. “We still catch halibut, tuna and rockfish,” said Pagaling, who is a Chumash tribal marine consultant as well as a trained rescue diver. “But these marine ecosystems are not as healthy as when our ancestors were eating the fish.” Pagaling is the board president of the nonprofit Ocean Origins, and she collaborates with marine scientists to restore one of the planet’s most precious resources: the kelp forests that once grew thick and wide in tidal corridors up and down the Pacific Coast.

Kelp forests keep ocean waters clean and oxygenated while hosting a wide variety of fish and sea life. These green and amber stalks of aquatic vegetation, which grow up to 175 feet from the seafloor to the surface, not only combat pollution but also mitigate climate change. Kelp forests absorb carbon dioxide from both the air and water that would otherwise linger for centuries. They can absorb 20 times more CO2 compared with same-size terrestrial forests.

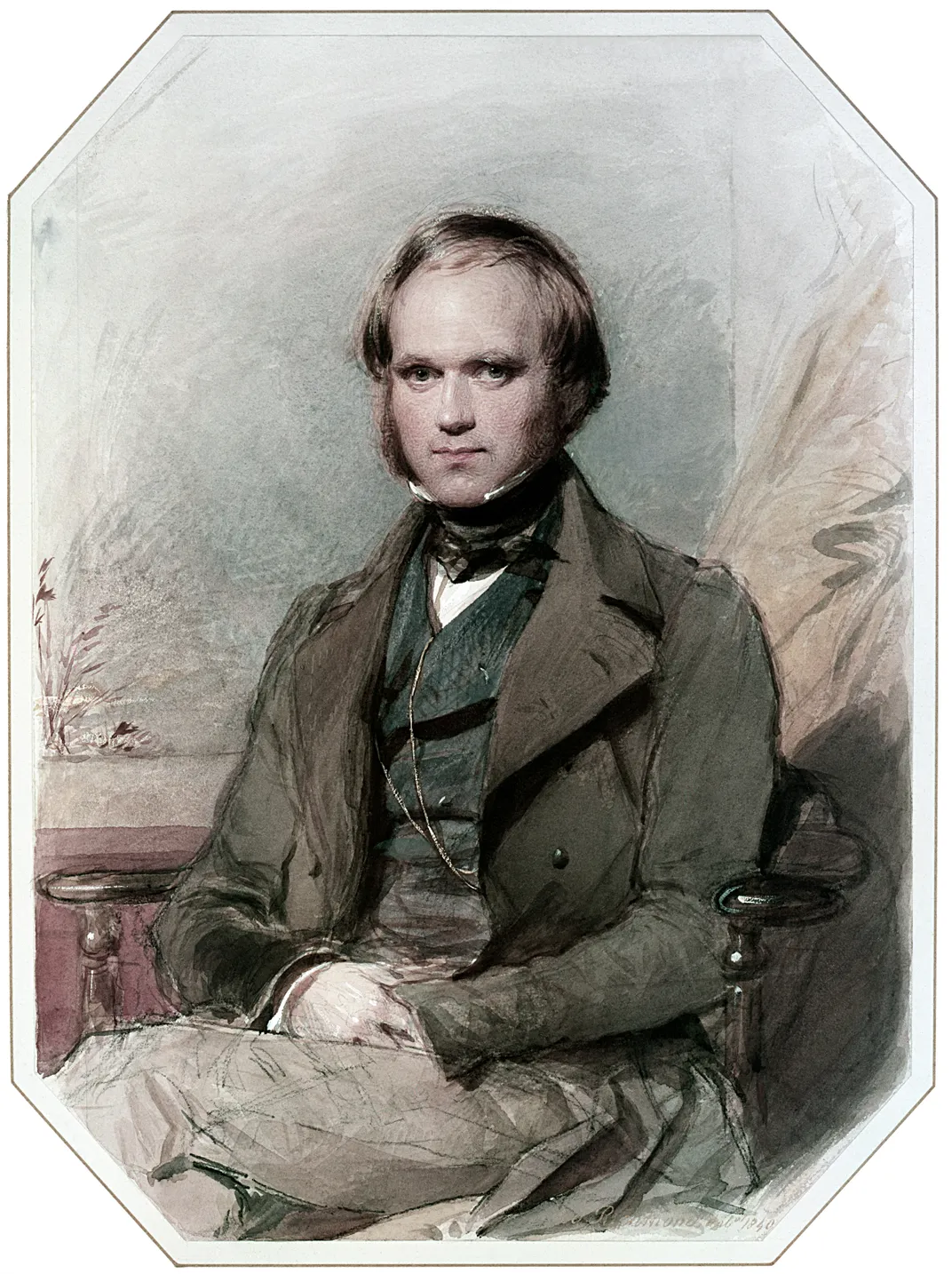

In the 1830s, Charles Darwin was amazed by the kelp ecosystems he found flourishing in the Pacific waters around the Galápagos. “I can only compare these great aquatic forests ... with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions,” he wrote in his journal. “Yet, if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish as would here, from the destruction of the kelp.”

Kelp is an umbrella term for 30 types of algae that grow along nearly a third of the world’s coastlines—in Maine and Long Island, in the United Kingdom and Norway, in Tasmania and southern Africa, in Argentina and Japan. With a global coverage of more than two million square miles, kelp takes up roughly the same space as the Amazon rainforest. But few places in recorded history have had more abundant kelp forests than the 840 miles along California’s coastline.

Over the past few hundred years, that changed. First came the 18th-century fur traders, who trapped the sea otters of Monterey Bay, natural predators of the purple urchins that feast on kelp stalks, stems and blades. By the early 20th century, otter populations were hunted to near extinction. Kelp beds were consumed until they turned into desolate underwater areas known as urchin barrens. Fish populations disappeared with the kelp.

Fun Fact: What is kelp, anyway?

- Kelp isn’t a plant. It’s a very large type of algae that can grow to be 150 feet tall.

- Gas-filled compartments allow kelp blades to float upright. Tangled extensions keep them anchored to the seafloor.

Then came the rise of the automobile. In 1921, California created the world’s first tidelands oil and gas leasing program, attracting energy producers that drilled hundreds of offshore oil wells across the Santa Barbara Channel. Oil platforms rose up from the sea. Oil leaks became common, along with the bubbling up of ocean floor tars. On January 28, 1969, one of the Union Oil Company’s main offshore platforms had a blowout, the largest in U.S. history at the time. As many as 4.2 million gallons of crude oil poured into the sea, killing thousands of seabirds, seals and sea lions, and also destroying the kelp forests.

The drilling didn’t stop, but mass protests and the burgeoning environmental movement pushed the federal government to set aside certain tidal waters as nature reserves. In 1980, the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary began protecting endangered species and sensitive habitats in nearly 1,500 square miles of ocean waters around the five northern Channel Islands. Yet the channel waters by Santa Barbara’s mainland remained open to drilling and industrial uses.

In recent years, the most destructive culprit has been climate change. From 2013 to 2016, the entire Pacific coast was hit with unprecedented El Niño events, when differentials in global winds and air temperatures set off superstorms. In 2015 alone, 16 tropical cyclones roiled the central Pacific hurricane basin, with rising water temperatures whacking kelp ecosystems out of balance. Nick Bond, climatologist for the state of Washington, called this marine heat wave “The Blob,” after the 1958 B-movie. Some kelp beds lingered in remnants, while others disappeared almost entirely, replaced by piles of purple urchins.

“It’s like seeing a forest that’s been clear-cut,” said marine conservationist Norah Eddy, the associate director of oceans programs for the Nature Conservancy in California. “It’s that shocking.”

In 2015, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council submitted a nomination to the federal government for its own marine protected area. In November 2024, it became official. The Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary now begins at the tip of the Channel Islands and stretches north over 116 miles of shore, more than 13 percent of California’s coastline. More than 4,500 square miles of tidal waters are now protected from offshore oil drilling, pollution, industrial development, overfishing and habitat destruction. I wanted to see a healthy kelp forest for myself.

On a chilly December morning, right after sunrise, I arrived at Ventura Harbor to board a dive boat for an all-day excursion with a couple dozen other kelp forest explorers. My scuba skills were rusty, so I opted to snorkel, renting gear and a wet suit.

On board was Selena Smith, a marine biologist who co-founded Ocean Origins along with Pagaling and two others. Smith also served as director of education at the Reef Check Foundation, a global organization that documents both coral reefs and kelp forests. On the choppy, two-hour outbound boat ride, Smith told me about how advanced ecological modeling, genetic studies of kelp and underwater mapping are being deployed for restoration projects. By learning how and why the algae thrive under certain conditions, Ocean Origins aims to restore kelp in many locations. Its team members regularly find plastic and other trash stuck in the blades. “Mylar balloons are horrible,” Smith said. “They are definitely harmful to the marine environment and its occupants.”

The boat dropped anchor in a spot so close to the ancient volcanic rock of Limuw that we could almost peer into the sea caves that line its shores. The surface of the water was teeming with kelp, so it looked like we had come to the right place. I took a ladder down to a small platform and let myself fall backward into the sea.

The 55-degree water was perfect for kelp growth, and magnificent visibility offered pristine views of the underwater forest. I swam toward the stalks until I found myself inside amber cathedrals of giant kelp, a robust species native to Southern California. A group of whiskered sea lions came out to greet us. With bodies twice as long as otters’, and leathery skin rather than fur, the lions police these places, feasting on fish to maintain their weight. For males, that can be upwards of 700 pounds.

The kelp reefs were a riot of color—populated with emerald, navy and ginger fish; spindly lobsters with bright yellow eyes; golden sea stars; anemones with magenta tentacles that gave a turquoise glow; and kelp shaped like olive feather boas and butterscotch bulbs. More than a thousand documented species of plants and animals can be found here. Drawing many gazes from the divers were the nudibranchs—sea slugs that appeared in vibrant blue and orange. This ecosystem was thriving for one main reason: It had been cleaned up and then left alone. “Areas that are protected from fishing tend to have higher amounts of kelp, creating a better environment and generating more diversity,” Smith said. “This past year has been an especially good one.”

Over the decades, there have been several notable stories of successful kelp revival. In the waters near Monterey, scientists and enthusiasts boat out weekly to dive into and monitor the aquatic forests. Ever since 1984, the Monterey Bay Aquarium has been helping protect the local waters from pollution and industrial development. The Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, established in 1992, expanded the effort, and now some 3,000 sea otters thrive between Half Moon Bay near San Francisco and Point Conception near Santa Barbara. The kelp’s ebbs and flows depend mostly on water temperature.

Off the coast of Palos Verdes, a famed surfing spot 30 miles south of Los Angeles, marine biologist Tom Ford, CEO of the Bay Foundation, operates one of the world’s most impressive kelp restoration projects. After moving to the area in 1998, Ford went out scuba diving and encountered a kelp forest. “That was it,” he said. “I was hooked.” For his master’s degree at the University of California, Los Angeles, Ford studied the trajectories of loss and recovery of kelp all over the world, and the many creatures that depended on it. “If it’s gone,” he said, “they’re essentially homeless.”

By 2013, Ford was ready to start work with a group of student volunteers, but he had barely gotten going when the coast was hit by The Blob. “We stopped restoration work,” he said. What they found were ailing purple echinoderms as far as the eye could see. They had consumed all the kelp, and now they were starving.

“Their spines covered entire ocean floors like marble tile,” Ford told me. He and his team dove into the water and smashed urchins to death with hammers, which released nutrients that would nourish other marine creatures. It’s taken a decade of relentless work to clean out enough urchins and replenish the area. “We restarted this ecological machine so it could restore its own health,” Ford said. By 2024, a 70-acre forest, the size of about 53 football fields, became the biggest kelp restoration success story in the United States.

A year later, when I rode on the dive boat with Ford and his crew, the restoration area had grown to 80 acres, or around 60 football fields. We swam in the aftermath of a summer heat wave, with the water’s surface at a toasty 72 degrees. The heat was causing some of the kelp blades to disintegrate, clouding the waters. But Ford showed me how the same ocean bottom that once looked pale and dead was now covered in kelp stalks and green, red and brown algae. Healthy urchins were present in small numbers. Ford’s studies show that having fewer than three urchins per ten square feet keeps the ecosystem in balance. Yet he acknowledged that clearing out urchins by hand takes too long. He told me he’s looking forward to new tools and techniques that could make restoration easier and more productive.

When it comes to the economy and the planet, cultivating kelp is a worthwhile venture. Perhaps the most promising business model is an outfit called Ocean Rainforest, which had success growing sugar kelp in the Faroe Islands of the North Atlantic Ocean and chose the Santa Barbara Channel as its next locale. Its 86-acre giant kelp farm, created from scratch four miles offshore, grows kelp on ropes that are attached to buoys. The buoys have GPS devices on them, and the team does biweekly monitoring, taking measurements of water temperature, nutrients and salinity. “The entire farm is engineered as one unit,” Douglas Bush, the director of California operations for Ocean Rainforest, said.

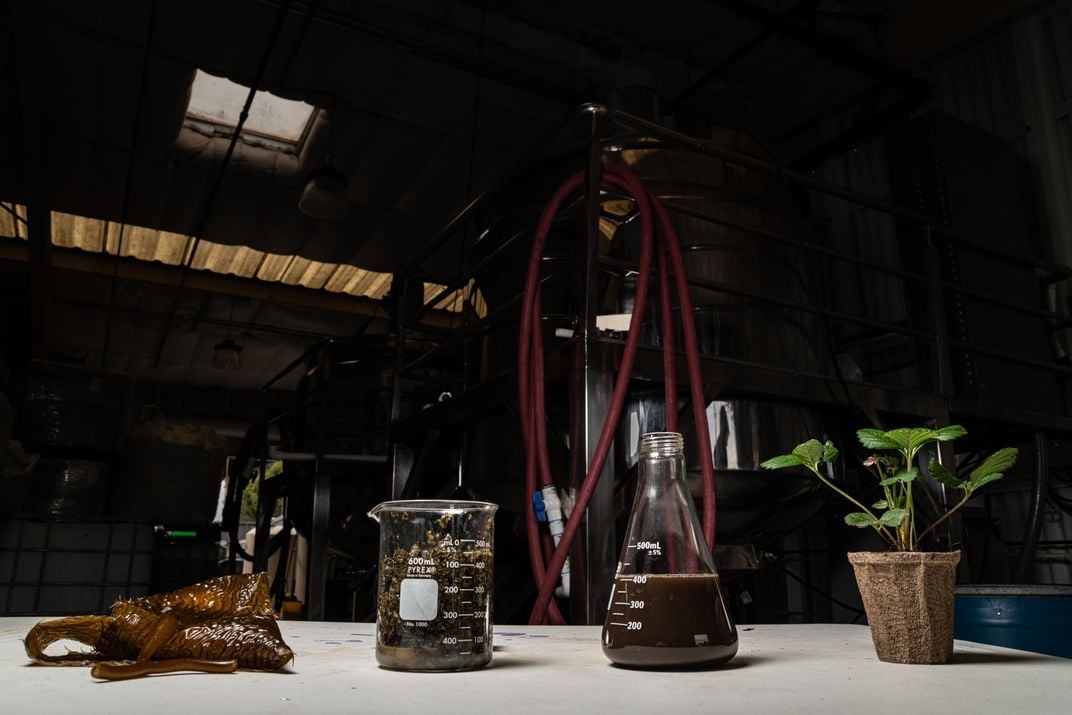

On a visit to his land-based facility in Goleta, California, Bush showed me giant metal vats that process the kelp into a liquid biostimulant for agriculture. By spraying this natural compound on soil, farmers hope to reduce the need for artificial fertilizers that give off nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas that traps 300 times as much heat per pound as CO2. The kelp-based product may boost yields and reduce the water needed for cash crops ranging from almonds and avocados to strawberries and grapes. (“Those are benefits attributed to seaweed biostimulants in general,” Bush noted carefully. “Our hope is to evaluate those claims in trials using our product.”)

Because California farms produce nearly half of America’s vegetables and three-quarters of its fruit and nuts, improving local agricultural techniques is no small achievement. “The reason we’re here is to be part of the solution, to improve regional food systems, to be a creative tool in the toolkit for regenerative agriculture,” Bush said. By cultivating kelp, he hopes to help meet the growing demand for seaweed products without putting strain on existing wild kelp forests.

Brian von Herzen, a planetary scientist who is the founder and executive director of the Climate Foundation—a nonprofit founded in California—believes that using kelp as a biostimulant for agriculture is a gigantic financial opportunity. “Furthermore, the seaweed forests play key roles in natural climate repair, which is essential at this late stage in our climate journey,” he said. Von Herzen and his team invented growing lattices with electric motors that lower seaweeds each night to absorb nutrients, and raise them up to the surface each morning to catch full sunlight and absorb carbon dioxide in the top few feet of the sea. This enables growth in areas that don’t have enough natural upwelling, due to warming waters. The foundation has a kelp farm in Philippines waters, where it sells a kelp-based fertilizer called BIGgrow.

In 2023, von Herzen’s group began hosting marine permaculture workshops in California to raise awareness. The group now collaborates with Ocean Origins, as well as with scientists at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Removing CO2 from the air is expensive with methods like direct-air capture machines, driven by giant fans. Each ton of carbon can cost as much as $1,000 to capture.

Von Herzen estimates that kelp can remove CO2 at a cost of just $20 to $85 per ton, without requiring any machinery. A single acre of kelp forest can take in 16 tons, von Herzen said, “but our arrays can do more than double that, 35 tons of CO2 per acre per year,” or about the annual emissions of six gasoline cars.

Existing global seaweed forests can capture nearly 200 million tons of CO2 a year while also giving a $500 billion boost in ecosystem services to industries including fishing. Expanding them is an excellent investment, said von Herzen, both financially and environmentally.

And using biostimulants can boost the climate benefit even more, both by reducing nitrous oxide emissions and by cutting the CO2 emissions that come both from making artificial fertilizers and from shipping them to farmers. California is already outpacing the rest of the country in reducing fossil fuel emissions. Kelp would help the state meet its target of reaching net-zero emissions by 2045, at least five years sooner than the Paris Agreement’s goal of 2050.

Seaweeds currently grow across nearly 1 percent of the world’s temperate coastal ocean waters. Getting back to pre-industrial levels of about 2 percent would be revolutionary. Von Herzen is focusing on specific species, which grow three times faster than other kelp. He said they could remove enough carbon to equal all emissions from global aviation—all flights using jet fuels everywhere in the world.

What’s more, studies show that kelp forests give off biogenic aerosols—tiny airborne particles that come from living things—that help clouds form. Coastal cloud cover reflects sunlight back into space. In its absence, the seas and soils are hotter, which also heats the air. There is more evaporation, and there are longer periods without rain. The ground becomes drier, making coastal woodlands more susceptible to wildfire. “We can keep California cooler and keep it from burning,” von Herzen said. “This can be done not in the distant future, but within the next ten years.” That’s because kelp can expand its coverage by 18 inches per day. Some giant kelp grow at a daily rate of two feet.

To take in the full glory of kelp, I flew to a set of seaside towns near Eureka, roughly 100 miles south of the Oregon border, that were playing host to the California Seaweed Festival, a two- or three-day event that pops up each year in different parts of the state. The festival, now in its sixth year, was co-founded by biologist Janet Kübler, who spelled out the challenges and opportunities for kelp in a 2021 paper in the Journal of the World Aquaculture Society. “It’s not just a conference,” Kübler told me. “It’s a celebration of seaweed, not just as a food or a carbon sink, but all of its possibilities.”

Inside the festival’s main venue at Eureka’s Wharfinger Building, a diverse set of scientists, including Indigenous leaders, was ready to point to their wall posters and chat about their research. Leaders of the Sunflower Star Lab were on hand to talk about recovery from The Blob, which brought about sea star wasting syndrome, all but killing off this keystone species, another natural predator of purple urchins. The stars, which stood in small tanks on display here, grow up to 39 inches wide. When they are released near a kelp forest, a slow-motion chase scene ensues. Urchins sense danger from chemicals released by the stars and try to escape. But the stars are speedier. Finally, a star will clutch and consume an urchin.

Outside, a bluegrass band called the Compost Mountain Boys played as attendees toured the farmer’s market. A stand operated by Sunken Seaweed, a startup that skyrocketed out of San Diego, drew much of the attention. The table was staffed by its co-founder Torre Polizzi, who sold me a $12 jar of Califurikake, a local twist on Japanese-style seasoning made from seaweed. The festival underscored the versatility of this underappreciated climate solution. I was familiar with kelp-based protein smoothies for humans, but I learned how sprinkling seaweed on cattle feed can help cows digest their food, reducing their methane emissions between 40 and 80 percent.

Kelp can also serve as an ingredient in biodegradable biopolymers, which are used in place of petroleum-based plastics. In 2020, a nonprofit called the Lonely Whale Foundation announced a $1.2 million Plastic Innovation Prize in partnership with Tom Ford Beauty (a company founded by fashion designer Tom Ford, not by marine biologist Tom Ford who runs the Bay Foundation). The top award, announced in 2023, went to a California company called Sway, which makes a seaweed-based alternative to thin-film plastic packaging.

At the docks, I boarded a boat for a Humboldt Bay harbor cruise. Out on the sparkling water, we spotted pelicans gliding in for a lunch of fish. The boat passed an aquatic farm established in 2020 that had produced more than 3,000 pounds of bull kelp that year. On the cruise, a Los Angeles company called Blue Robotics was showing images captured by a remotely operated vehicle that can help tend kelp several hundred feet underwater. At night, a party billed as the Seaweed Speakeasy featured local beers made with kelp instead of malt, served along with seaweedy hors d’oeuvres. I found a station serving mac and kelp and cheese that went down easy with the beer.

The festival culminated at the marine lab of Cal Poly Humboldt. Pulling on latex gloves, I stood beside a lab table set with fresh ribbons of kelp and learned how to assess its reproductive health by isolating the tissue that holds its spores. With a razor, I scraped a slimy layer off a blade, splashed it with iodine and set the substance under a microscope. The batch held spores with excellent motility (the ability to move well on their own). Each spore grows into a microscopic organism, either male or female. The males will release sperm into the water, and the females will release chemicals that help the sperm find their eggs.

I left the festival feeling satisfied and, dare I say, optimistic, yet with some big unresolved questions. Where was this kelp work heading? How big could the movement really get? What kinds of signs would urge people to take such solutions seriously? The last of these questions took on even more urgency for me in January, after winds up to 100 miles an hour hit Los Angeles, where I live. The gusts stoked flames on parched lands, creating Southern California’s most devastating winter fire in decades. The result: death, devastation and more than $75 billion in damages.

The average person may know the Earth is warmer now than at any time in the past 100,000 years, or that each year now sets a global temperature record. But what happens underwater is so rarely seen. Most people have no idea that seaweeds have been around for a billion years, or that algae and aquatic plants provide the planet with about half of its oxygen, the other half coming from terrestrial plants. Most people don’t know that ocean water has already absorbed about a third of humanity’s excess carbon emissions, and that the resulting carbonic acid disrupts the ocean’s chemistry, leaving less calcium for the hard shell casings of shellfish—or that cultivating kelp serves as a giant pushback against this process. Most people don’t know that seaweeds can be used to make natural, low-cost alternatives to plastics and fertilizers.

The Chumash people know all of this. I met Pagaling at Goleta Beach, near Santa Barbara, to chat on a bench by the playground, where her 4-year-old was having a wonderful time. Pagaling pointed to seaweed that had washed ashore on the sand and described how the Chumash had been gathering the stuff from beaches for centuries. She uses it as a fertilizer for her family’s garden of corn, squash, beans, carrots and zucchini. “You can watch the plants really take off,” she said.

As we gazed out at the ocean, she lamented the loss. “That’s where our food was provided, our staple areas, our swimming and fishing,” she said. Then came the pollution, the overfishing, the poor land and water management practices. Oil platforms are still visible to anyone driving north from Los Angeles along Highway 101. After a century of drilling, Californians have now spent more than a decade taking steps toward decommissioning the rigs. Still, as intrusive as the rigs once were, ecosystems have adapted around them. As with shipwrecks, the rigs are now habitats for arrays of marine life. That’s how resilient nature can be. Even many staunch environmentalists agree that the underwater structures should remain after they’re no longer in use.

Pagaling spoke of the celebrations on the Chumash reservation when the federal government approved the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary and the outlook for leading restoration of nature along the coast. “There are so many kelp forest opportunities now,” she said. “It will take collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups.” Yet she acknowledged that there have been few collaborations like this before. “Lots of communities say they are for restoration, but there is often disagreement over how.”

When the tomol crew reaches Limuw, a crowd of people from the Chumash community and beyond will welcome those who paddled all through the night. Next year, Pagaling says, the gathering won’t only be about honoring the past. It will also celebrate the possibility of a better future.