Indigenous groups fight to save rediscovered settlement site on Texas coast

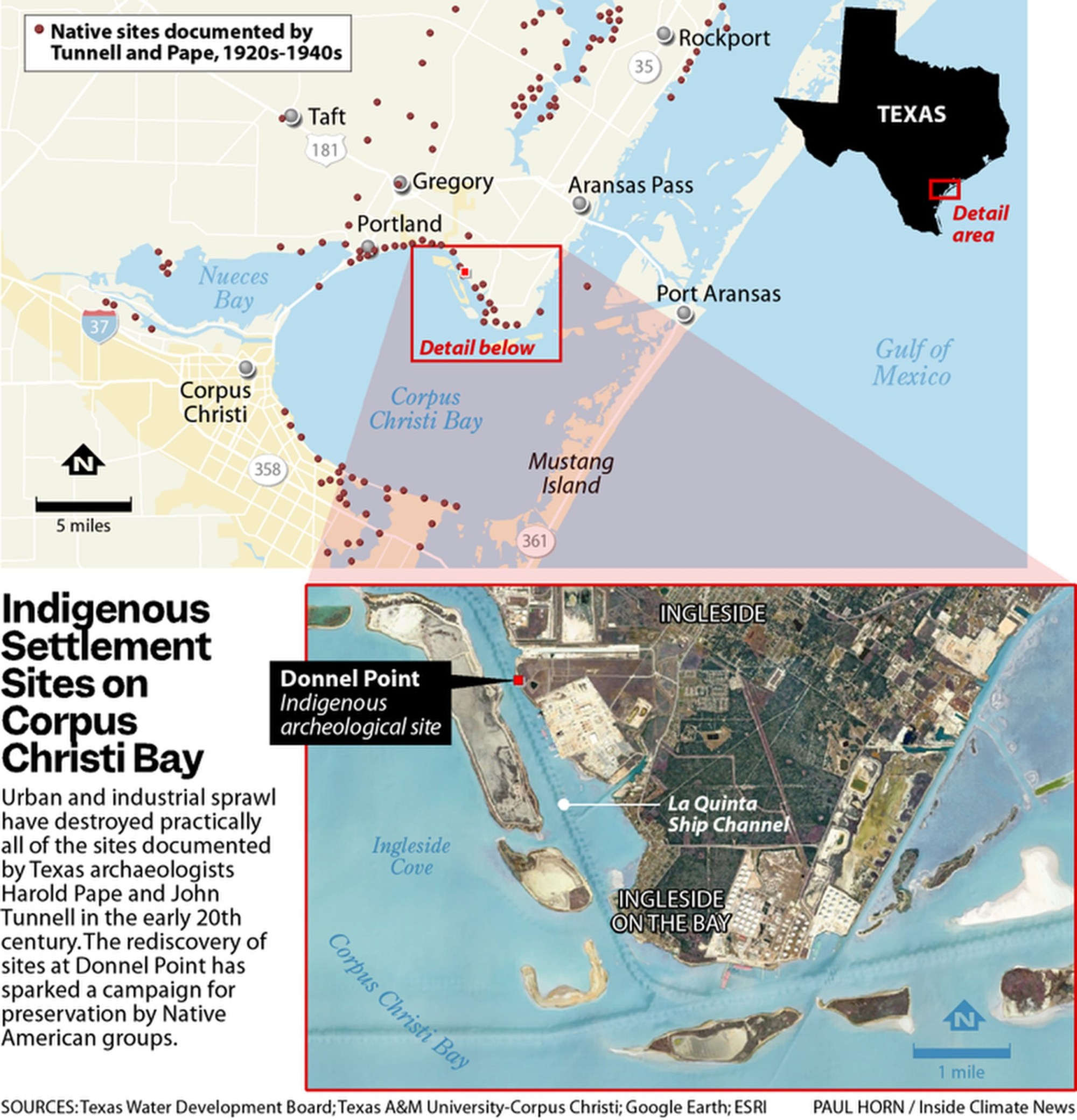

Audio recording is automated for accessibility. Humans wrote and edited the story. See our AI policy, and give us feedback. This story is published in partnership with Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for the ICN newsletter here. INGLESIDE — The rediscovery of an ancient settlement site, sandwiched between industrial complexes on Corpus Christi Bay, has spurred a campaign for its preservation by Native American groups in South Texas. Hundreds of such sites were once documented around nearby bays but virtually all have been destroyed as cities, refineries and petrochemical plants spread along the waterfront at one of Texas’ commercial ports. In a letter last month, nonprofit lawyers representing the Karankawa and Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to revoke an unused permit that would authorize construction of an oil terminal at the site, called Donnel Point, among the last undisturbed tracts of land on almost 70 miles of shoreline. “We’re not just talking about a geographical point on the map,” said Love Sanchez, a 43-year-old mother of two and a Karankawa descendent in Corpus Christi. “We’re talking about a place that holds memory.” The site sits on several hundred acres of undeveloped scrubland, criss-crossed by wildlife trails with almost a half mile of waterfront. It was documented by Texas archaeologists in the 1930s but thought to be lost to dredging of an industrial ship canal in the 1950s. Last year a local geologist stumbled upon the site while boating on the bay and worked with a local professor of history to identify it in academic records. For Sanchez, a former office worker at the Corpus Christi Independent School District, Donnel Point represents a precious, physical connection to a past that’s been largely covered up. She formed a group called Indigenous Peoples of the Coastal Bend in 2018 to raise awareness about the unacknowledged Indigenous heritage of this region on the middle Texas coast. The names and tales of her ancestors here were lost to genocide in Texas. Monuments now say her people went extinct. But the family lore, earthy skin tones and black, waxy hair of many South Texas families attest that Indigenous bloodlines survived. For their descendents, few sites like Donnel Point remain as evidence of how deep their roots here run. “Even if the stories were taken or burned or scattered, the land still remembers,” Sanchez said. The land tells a story at odds with the narrative taught in Texas schools, that only sparse bands of people lived here when American settlers arrived. Instead, the number and ages of settlement sites documented around the bay suggest that its bounty of fish and crustaceans supported thriving populations. “This place was like a magnet for humans,” said Peter Moore, a professor of early American history at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi who identified the site at Donnel Point. “Clearly, this was a densely settled place.” There’s no telling how many sites have been lost, he said, especially to the growth of the petrochemical industry. The state’s detailed archaeological records are only available to licensed archaeologists, who are contracted primarily by developers. A few sites were excavated and cataloged before they were destroyed. Many others disappeared anonymously. Their remains now lie beneath urban sprawl on the south shore of Corpus Christi Bay and an industrial corridor on its north. “Along a coastline that had dense settlements, they’re all gone,” Moore said. The last shell midden Rediscovery of the site at Donnel Point began last summer when Patrick Nye, a local geologist and retired oilman, noticed something odd while boating near the edge of the bay: a pile of bright white oyster, conch and scallop shells spilling from the brush some 15 feet above the water and cascading down the steep, clay bank. Nye, 71, knew something about local archaeology. Growing up on this coastline he amassed a collection of thousands of pot shards and arrowheads (later donated to a local Indigenous group) from a patch of woods near his home just a few miles up the shore, a place called McGloins Bluff. Nye’s father, chief justice of the local court of civil appeals, helped save the site from plans by an oil company to dump dredging waste there in 1980. Later, in 2004, the Port of Corpus Christi Authority, which owned the tract, commissioned the excavation and removal of about 40,000 artifacts so it could sell the land to a different oil company for development, against the recommendations of archaeological consultants and state historical authorities. Patrick Nye pilots his boat on Corpus Christi Bay at daybreak on Dec. 7, 2025. Dylan Baddour/Inside Climate News“We’re not going to let that happen here,” Nye said on a foggy morning in December as he steered his twin engine bay boat up to Donnel Point, situated between a chemical plant and a construction yard for offshore oil rigs on land owned by the Port of Corpus Christi Authority. Nye returned to the site with Moore, who taught a class at Texas A&M University about the discovery in 1996 and subsequent destruction of a large cemetery near campus called Cayo del Oso, where construction crews found hundreds of burials dating from 2,800 years ago until the 18th century. It now sits beneath roads and houses of Corpus Christi’s Bay Area. Moore consulted the research of two local archaeologists, a father and son-in-law duo named Harold Pape and John Tunnell who documented hundreds of Indigenous cultural sites around nearby bays in the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, including a string of particularly dense settlements on the north shore of Corpus Christi Bay. Their work was only published in 2015 by their descendents, John Tunnell Jr. and his son Jace Tunnell, both professors at A&M. Moore looked up the location that Nye had described, and there he found it — a hand-drawn map of a place called Donnel Point, with six small Xs denoting “minor sites” and two circles for “major sites.” A map produced by Pape and Tunnell showing Donnel Point, then called Boyd’s Point, in 1940, with several major and minor archaeological sites marked. Used with permission. Tunnell, J. W., & Tunnell, J. (2015). Pioneering archaeology in the Texas coastal bend : The Pape-Tunnell collection. Texas A&M University Press.The map also showed a wide, sandy point jutting 1,000 feet into Corpus Christi Bay, which no longer exists. It was demolished by dredging for La Quinta Ship Channel in the 1950s. Moore’s research found a later archaeological survey of the area ordered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1970s concluded the sites on Donnel Point were lost. “Subsequent archeological reports repeated this assumption,” said an eight-page report Moore produced last year on the rediscovery of the sites. The artifacts at Donnel Point are probably no different than those collected from similar sites that have been paved over. The sites’ largest features are likely the large heaps of seashells, called middens, left by generations of fishermen eating oysters, scallops and conchs. “Even if it’s just a shell midden, in some ways it’s the last shell midden,” Moore said at a coffee shop in Corpus Christi. “It deserves special protection.” Nye and Moore took their findings to local Indigenous groups, who quietly began planning a campaign for preservation. Seashells spilling down the edge of a tall, clay bank, 15 feet above the water, on Dec. 7, 2025. Dredging for an industrial ship channel and subsequent erosion cut into these shell middens left by generations of indigenous fishermen. Dylan Baddour/Inside Climate NewsA mistaken extinction Under the law, preservation often means excavating artifacts before sites are paved over. But the descendents of these coastal cultures are less concerned about the scraps and trinkets their ancestors left behind as they are about the place itself. In most cases they can only guess where the old villages stood before they were erased. In this rare case they know. Now they would like to visit. “Not only are we fighting to maintain a sacred place, we’re trying to maintain a connection that we’ve had over thousands and thousands of years,” said Juan Mancias, chair of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, during a webinar in November to raise awareness about the site. The destruction of these sites furthers the erasure of Indigenous people from Texas, he said. He has fought for years against the planned destruction of another village site called Garcia Pasture, which is slated to become an LNG terminal at the Port of Brownsville, south of Corpus Christi. North of Corpus Christi, near Victoria, a large, 7,000-year-old cemetery was exhumed in 2006 for a canal expansion at a plastics plant. “The petrochemical industry has to understand that we’re going to stand in the way of their so-called progress,” Mancias, a 71-year-old former youth social worker, said during the webinar. “They have total disregard for the land because they have no connection. They’re immigrants.” He grew up picking cotton with other Mexican laborers in the Texas Panhandle. But his grandparents told him stories about the ancient forests and villages of the lower Rio Grande that they’d been forced to flee. His schooling and history books told him the stories couldn’t be true. They said the Indigenous people of South Texas vanished long ago and offered little interest or insight into how they lived. It was through archaeological sites that Mancias later confirmed the places in his grandparents’ stories existed. There is no easy pathway for Mancias to protect these sites. Neither the Carrizo/Comecrudo or the Karankawa, who inhabited the coastal plains of Texas and Tamaulipas, are among the federally recognized tribes that were resettled by the U.S. government onto reservations. Only federally recognized tribes have legal rights to archaeological sites in their ancestral territory. As far as U.S. law is concerned, the native peoples of South Texas no longer exist, leaving the lands they once occupied ripe for economic development. “Now it’s the invaders who decide who and what we are,” said Mancias in an interview. “That’s why we struggle with our own identities.” Juan Mancias, chair of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, at an H-E-B grocery store in Port Isabel in 2022. Dylan Baddour/Inside Climate NewsIn Corpus Christi, the story of Indigenous extinction appears on a historical marker placed prominently at a bayside park in commemoration of the Karankawa peoples. “Many of the Indians were killed in warfare,” it says. “Remaining members of the tribe fled to Mexico about 1843. Annihilation of that remnant about 1858 marked the disappearance of the Karankawa Indians.” That isn’t true, according to Tim Seiter, an assistant professor of history at the University of Texas at Tyler who studies Karankawa history. While Indigenous communities ceased to exist openly, not every last family was killed. Asserting extinction, he said, is another means of conquest. “This is very much purposefully done,” he said. “If the Karakawas go extinct, they can’t come back and reclaim the land.” Stories of survival Almost a century before the English pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, the Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca lived with and wrote about the Karankawas — a diverse collection of bands and clans that shared a common language along the Gulf Coast. By the time Anglo-American settlers began to arrive in Texas, the Karankawas were 300 years acquainted with Spanish language and culture. Some of them settled in or around Spanish missions as far inland as San Antonio. Many had married into the new population of colonial Texas. Many of their descendants still exist today. “We just call those people Tejanos, or Mexicans,” said Seiter, who grew up near the Gulf coast outside Houston. Love Sanchez with her mother and two sons at a park in Corpus Christi in 2022. Dylan Baddour/Inside Climate NewsHe made those connections through Spanish records at archives in San Antonio. In Texas’ Anglo-American era, Seiter said, most available information about the Karankawas comes from the diaries of settlers who are trying to exterminate them. Some of the last stories of the Karankawas written into history involve settler militias launching surprise attacks on Karankawa settlements and gunning down men, women and children as they fled across a river. “The documents are coming from the colonists and they’re not keeping tabs of who they are killing in these genocidal campaigns,” Seiter said. “It makes it really hard to do ancestry.” All the accounts tell of Karankawa deaths and expulsion. Stories of survivors and escapees never made it into the record. But Seiter said he’s identified individuals through documents who survived massacres. Moreover, oral histories of Hispanic families say many others escaped, hid their identities and fled to Mexico or integrated into Anglo society. That’s one reason why archaeological sites like Donnel Point are so important, Seiter said: They are a record that was left by the people themselves, rather than by immigrant writers. The lack of information leaves a lot of mystery in the backgrounds of people like Sanchez, founder of Indigenous Peoples of the Coastal Bend in Corpus Christi. She was born in Corpus Christi to parents from South Texas and grandparents from Mexico. Almost 20 years ago her cousin shared the results of a DNA test showing their mixed Indigenous ancestry from the Gulf Coast region. Curious to learn more, she sought out a local elder named Larry Running Turtle Salazar who she had seen at craft markets. Salazar gained prominence and solidified a small community around a campaign to protect the Cayo del Oso burial ground. Through Salazar, Sanchez learned about local Indigenous culture and history. Then she was jolted to action after 2016, when she followed online as Native American protesters gathered on the Standing Rock Lakota Reservation to block an oil company from laying its pipeline across their territory. The images of Indigenous solidarity, and of protesters pepper sprayed by oil company security, inflamed Sanchez’s emotions. She began attending small protests in Corpus Christi. When Salazar announced his retirement from posting on social media, exhausted by all the hate, Sanchez said she would take up the task fighting for awareness of Indigenous heritage. “People don’t want us to exist,” she said beneath mesquite trees at a park in Corpus Christi. “Sometimes they are really mean.” In 2018 she formed her group, Indigenous Peoples of the Coastal Bend, which she now operates full time, visiting schools and youth groups to tell about the Karankawa and help kids learn to love their local ecosystems. Over time the group has become increasingly focused on environmental protection from expansion of the fossil fuel industry. Salazar died in March at 68. Chemours Chemical plant on La Quinta Ship Channel, adjacent to the site of Donnel Point in 2022. Dylan Baddour/Inside Climate NewsProtecting Donnel Point When Nye and Moore shared their discovery with Sanchez, who has always dreamed of becoming a lawyer, she knew it had to be kept secret while a legal strategy was devised, lest the site’s developers rush to beat them. The groups brought their case to nonprofit lawyers at Earthjustice and the University of Texas School of Law Environmental Clinic, who filed records requests to turn up available information on the property. “We discovered that they had this old permit that had been extended and transferred,” said Erin Gaines, clinical professor at the clinic. “Then we started digging in on that.” The permit was issued in 2016 by USACE to the site’s previous owner, Cheniere, to build an oil condensate terminal, then transferred to the Port of Corpus Christi Authority, administrator of the nation’s top port for oil exports, when it bought the land in 2021. Since then, the Port has sought developers to build and operate a terminal in the space, the lawyers found, even though proposed layouts and environmental conditions differ greatly from the project plans reviewed for the 2016 permit. In November, Sanchez and the other groups announced their campaign publicly when their lawyers filed official comments with USACE, requesting that the permit for the site be revoked or subject to new reviews. The Port of Corpus Christi Authority did not respond to a request for comment. “Cultural information and environmental conditions at the site have changed, necessitating new federal reviews and a new permit application,” the comments said. “Local residents and researchers have re-discovered an archaeological site in the project area, consisting of a former settlement that was thought to be lost and is of great importance to the Karankawa and Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribes.” Still, the site faces a slim shot at preservation. First it would need to be flagged by the Texas Historical Commission. But the commissioners there are appointed by Gov. Greg Abbott, who has received $40 million in campaign contributions from the oil and gas industry since taking office. Even then, preservation under the law means digging up artifacts and putting them in storage so the site can be cleared for development. Only under exceptional circumstances could it be protected in an undisturbed state. Neither Abbott’s office nor the Texas Historical Commission responded to a request for comment. Despite the odds, Sanchez dreams of making Donnel Point a place that people could visit to feel their ancestors’ presence and imagine the thousands of years that they fished from the bay. The fossil fuel industry is a towering opponent, but she’s used to it here. She plans to never give up. “In this type of organizing you can lose hope really fast,” she said. “No one here has lost hope.” Disclosure: H-E-B, Texas A&M University, Texas A&M University Press and Texas Historical Commission have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Flanked by a chemical plant and an oil rig construction yard, the site on Corpus Christi Bay may be the last of its kind on this stretch of coastline, now occupied by petrochemical facilities.

This story is published in partnership with Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for the ICN newsletter here.

INGLESIDE — The rediscovery of an ancient settlement site, sandwiched between industrial complexes on Corpus Christi Bay, has spurred a campaign for its preservation by Native American groups in South Texas.

Hundreds of such sites were once documented around nearby bays but virtually all have been destroyed as cities, refineries and petrochemical plants spread along the waterfront at one of Texas’ commercial ports.

In a letter last month, nonprofit lawyers representing the Karankawa and Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to revoke an unused permit that would authorize construction of an oil terminal at the site, called Donnel Point, among the last undisturbed tracts of land on almost 70 miles of shoreline.

“We’re not just talking about a geographical point on the map,” said Love Sanchez, a 43-year-old mother of two and a Karankawa descendent in Corpus Christi. “We’re talking about a place that holds memory.”

The site sits on several hundred acres of undeveloped scrubland, criss-crossed by wildlife trails with almost a half mile of waterfront. It was documented by Texas archaeologists in the 1930s but thought to be lost to dredging of an industrial ship canal in the 1950s. Last year a local geologist stumbled upon the site while boating on the bay and worked with a local professor of history to identify it in academic records.

For Sanchez, a former office worker at the Corpus Christi Independent School District, Donnel Point represents a precious, physical connection to a past that’s been largely covered up. She formed a group called Indigenous Peoples of the Coastal Bend in 2018 to raise awareness about the unacknowledged Indigenous heritage of this region on the middle Texas coast.

The names and tales of her ancestors here were lost to genocide in Texas. Monuments now say her people went extinct. But the family lore, earthy skin tones and black, waxy hair of many South Texas families attest that Indigenous bloodlines survived. For their descendents, few sites like Donnel Point remain as evidence of how deep their roots here run.

“Even if the stories were taken or burned or scattered, the land still remembers,” Sanchez said.

The land tells a story at odds with the narrative taught in Texas schools, that only sparse bands of people lived here when American settlers arrived. Instead, the number and ages of settlement sites documented around the bay suggest that its bounty of fish and crustaceans supported thriving populations.

“This place was like a magnet for humans,” said Peter Moore, a professor of early American history at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi who identified the site at Donnel Point. “Clearly, this was a densely settled place.”

There’s no telling how many sites have been lost, he said, especially to the growth of the petrochemical industry. The state’s detailed archaeological records are only available to licensed archaeologists, who are contracted primarily by developers. A few sites were excavated and cataloged before they were destroyed. Many others disappeared anonymously. Their remains now lie beneath urban sprawl on the south shore of Corpus Christi Bay and an industrial corridor on its north.

“Along a coastline that had dense settlements, they’re all gone,” Moore said.

The last shell midden

Rediscovery of the site at Donnel Point began last summer when Patrick Nye, a local geologist and retired oilman, noticed something odd while boating near the edge of the bay: a pile of bright white oyster, conch and scallop shells spilling from the brush some 15 feet above the water and cascading down the steep, clay bank.

Nye, 71, knew something about local archaeology. Growing up on this coastline he amassed a collection of thousands of pot shards and arrowheads (later donated to a local Indigenous group) from a patch of woods near his home just a few miles up the shore, a place called McGloins Bluff.

Nye’s father, chief justice of the local court of civil appeals, helped save the site from plans by an oil company to dump dredging waste there in 1980. Later, in 2004, the Port of Corpus Christi Authority, which owned the tract, commissioned the excavation and removal of about 40,000 artifacts so it could sell the land to a different oil company for development, against the recommendations of archaeological consultants and state historical authorities.

“We’re not going to let that happen here,” Nye said on a foggy morning in December as he steered his twin engine bay boat up to Donnel Point, situated between a chemical plant and a construction yard for offshore oil rigs on land owned by the Port of Corpus Christi Authority.

Nye returned to the site with Moore, who taught a class at Texas A&M University about the discovery in 1996 and subsequent destruction of a large cemetery near campus called Cayo del Oso, where construction crews found hundreds of burials dating from 2,800 years ago until the 18th century. It now sits beneath roads and houses of Corpus Christi’s Bay Area.

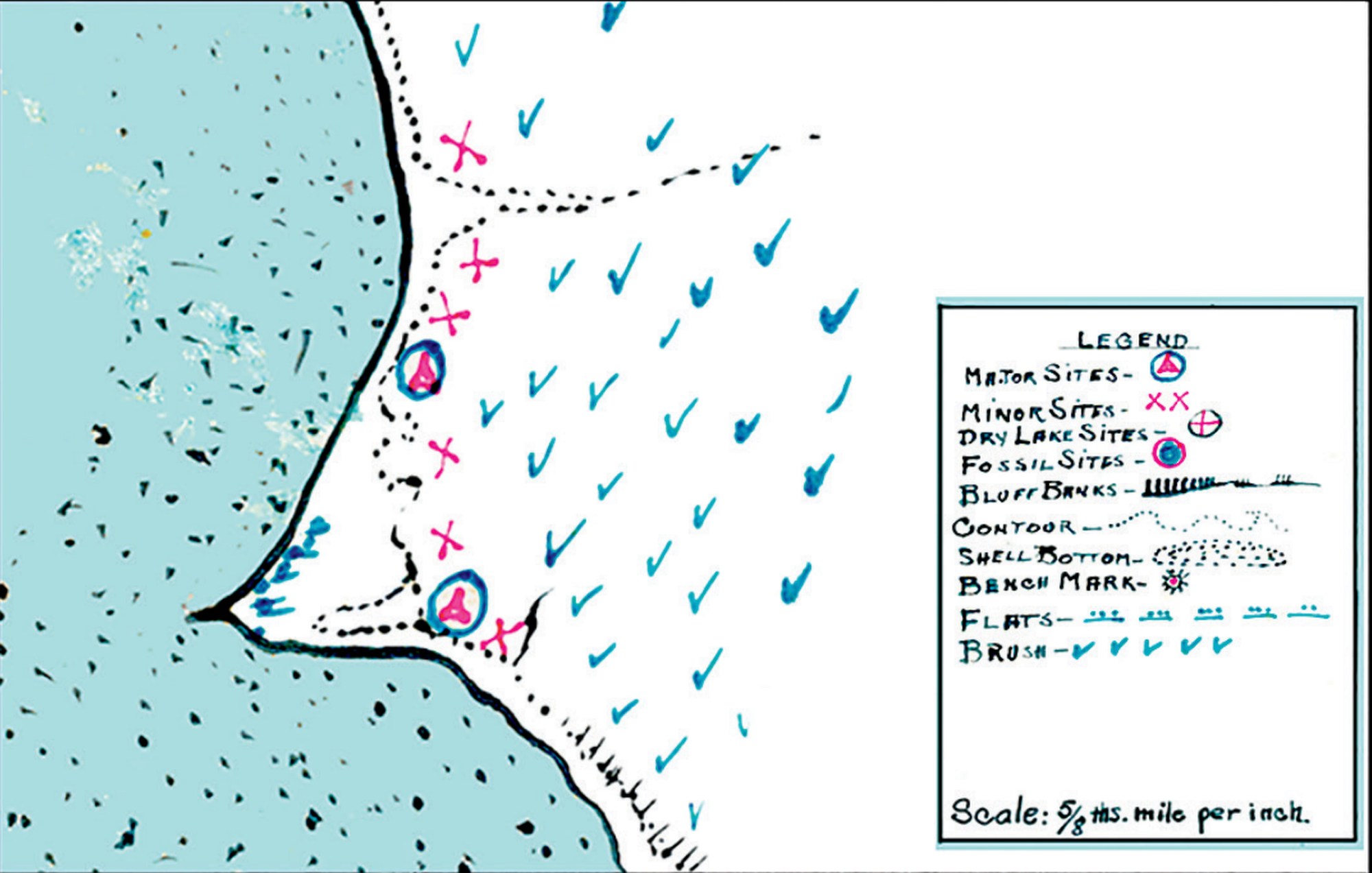

Moore consulted the research of two local archaeologists, a father and son-in-law duo named Harold Pape and John Tunnell who documented hundreds of Indigenous cultural sites around nearby bays in the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, including a string of particularly dense settlements on the north shore of Corpus Christi Bay. Their work was only published in 2015 by their descendents, John Tunnell Jr. and his son Jace Tunnell, both professors at A&M.

Moore looked up the location that Nye had described, and there he found it — a hand-drawn map of a place called Donnel Point, with six small Xs denoting “minor sites” and two circles for “major sites.”

The map also showed a wide, sandy point jutting 1,000 feet into Corpus Christi Bay, which no longer exists. It was demolished by dredging for La Quinta Ship Channel in the 1950s.

Moore’s research found a later archaeological survey of the area ordered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1970s concluded the sites on Donnel Point were lost.

“Subsequent archeological reports repeated this assumption,” said an eight-page report Moore produced last year on the rediscovery of the sites.

The artifacts at Donnel Point are probably no different than those collected from similar sites that have been paved over. The sites’ largest features are likely the large heaps of seashells, called middens, left by generations of fishermen eating oysters, scallops and conchs.

“Even if it’s just a shell midden, in some ways it’s the last shell midden,” Moore said at a coffee shop in Corpus Christi. “It deserves special protection.”

Nye and Moore took their findings to local Indigenous groups, who quietly began planning a campaign for preservation.

A mistaken extinction

Under the law, preservation often means excavating artifacts before sites are paved over. But the descendents of these coastal cultures are less concerned about the scraps and trinkets their ancestors left behind as they are about the place itself.

In most cases they can only guess where the old villages stood before they were erased. In this rare case they know. Now they would like to visit.

“Not only are we fighting to maintain a sacred place, we’re trying to maintain a connection that we’ve had over thousands and thousands of years,” said Juan Mancias, chair of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, during a webinar in November to raise awareness about the site.

The destruction of these sites furthers the erasure of Indigenous people from Texas, he said. He has fought for years against the planned destruction of another village site called Garcia Pasture, which is slated to become an LNG terminal at the Port of Brownsville, south of Corpus Christi. North of Corpus Christi, near Victoria, a large, 7,000-year-old cemetery was exhumed in 2006 for a canal expansion at a plastics plant.

“The petrochemical industry has to understand that we’re going to stand in the way of their so-called progress,” Mancias, a 71-year-old former youth social worker, said during the webinar. “They have total disregard for the land because they have no connection. They’re immigrants.”

He grew up picking cotton with other Mexican laborers in the Texas Panhandle. But his grandparents told him stories about the ancient forests and villages of the lower Rio Grande that they’d been forced to flee.

His schooling and history books told him the stories couldn’t be true. They said the Indigenous people of South Texas vanished long ago and offered little interest or insight into how they lived. It was through archaeological sites that Mancias later confirmed the places in his grandparents’ stories existed.

There is no easy pathway for Mancias to protect these sites. Neither the Carrizo/Comecrudo or the Karankawa, who inhabited the coastal plains of Texas and Tamaulipas, are among the federally recognized tribes that were resettled by the U.S. government onto reservations.

Only federally recognized tribes have legal rights to archaeological sites in their ancestral territory. As far as U.S. law is concerned, the native peoples of South Texas no longer exist, leaving the lands they once occupied ripe for economic development.

“Now it’s the invaders who decide who and what we are,” said Mancias in an interview. “That’s why we struggle with our own identities.”

In Corpus Christi, the story of Indigenous extinction appears on a historical marker placed prominently at a bayside park in commemoration of the Karankawa peoples.

“Many of the Indians were killed in warfare,” it says. “Remaining members of the tribe fled to Mexico about 1843. Annihilation of that remnant about 1858 marked the disappearance of the Karankawa Indians.”

That isn’t true, according to Tim Seiter, an assistant professor of history at the University of Texas at Tyler who studies Karankawa history. While Indigenous communities ceased to exist openly, not every last family was killed. Asserting extinction, he said, is another means of conquest.

“This is very much purposefully done,” he said. “If the Karakawas go extinct, they can’t come back and reclaim the land.”

Stories of survival

Almost a century before the English pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, the Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca lived with and wrote about the Karankawas — a diverse collection of bands and clans that shared a common language along the Gulf Coast. By the time Anglo-American settlers began to arrive in Texas, the Karankawas were 300 years acquainted with Spanish language and culture.

Some of them settled in or around Spanish missions as far inland as San Antonio. Many had married into the new population of colonial Texas. Many of their descendants still exist today.

“We just call those people Tejanos, or Mexicans,” said Seiter, who grew up near the Gulf coast outside Houston.

He made those connections through Spanish records at archives in San Antonio. In Texas’ Anglo-American era, Seiter said, most available information about the Karankawas comes from the diaries of settlers who are trying to exterminate them.

Some of the last stories of the Karankawas written into history involve settler militias launching surprise attacks on Karankawa settlements and gunning down men, women and children as they fled across a river.

“The documents are coming from the colonists and they’re not keeping tabs of who they are killing in these genocidal campaigns,” Seiter said. “It makes it really hard to do ancestry.”

All the accounts tell of Karankawa deaths and expulsion. Stories of survivors and escapees never made it into the record. But Seiter said he’s identified individuals through documents who survived massacres. Moreover, oral histories of Hispanic families say many others escaped, hid their identities and fled to Mexico or integrated into Anglo society.

That’s one reason why archaeological sites like Donnel Point are so important, Seiter said: They are a record that was left by the people themselves, rather than by immigrant writers.

The lack of information leaves a lot of mystery in the backgrounds of people like Sanchez, founder of Indigenous Peoples of the Coastal Bend in Corpus Christi. She was born in Corpus Christi to parents from South Texas and grandparents from Mexico. Almost 20 years ago her cousin shared the results of a DNA test showing their mixed Indigenous ancestry from the Gulf Coast region.

Curious to learn more, she sought out a local elder named Larry Running Turtle Salazar who she had seen at craft markets. Salazar gained prominence and solidified a small community around a campaign to protect the Cayo del Oso burial ground.

Through Salazar, Sanchez learned about local Indigenous culture and history. Then she was jolted to action after 2016, when she followed online as Native American protesters gathered on the Standing Rock Lakota Reservation to block an oil company from laying its pipeline across their territory.

The images of Indigenous solidarity, and of protesters pepper sprayed by oil company security, inflamed Sanchez’s emotions. She began attending small protests in Corpus Christi. When Salazar announced his retirement from posting on social media, exhausted by all the hate, Sanchez said she would take up the task fighting for awareness of Indigenous heritage.

“People don’t want us to exist,” she said beneath mesquite trees at a park in Corpus Christi. “Sometimes they are really mean.”

In 2018 she formed her group, Indigenous Peoples of the Coastal Bend, which she now operates full time, visiting schools and youth groups to tell about the Karankawa and help kids learn to love their local ecosystems. Over time the group has become increasingly focused on environmental protection from expansion of the fossil fuel industry. Salazar died in March at 68.

Protecting Donnel Point

When Nye and Moore shared their discovery with Sanchez, who has always dreamed of becoming a lawyer, she knew it had to be kept secret while a legal strategy was devised, lest the site’s developers rush to beat them.

The groups brought their case to nonprofit lawyers at Earthjustice and the University of Texas School of Law Environmental Clinic, who filed records requests to turn up available information on the property.

“We discovered that they had this old permit that had been extended and transferred,” said Erin Gaines, clinical professor at the clinic. “Then we started digging in on that.”

The permit was issued in 2016 by USACE to the site’s previous owner, Cheniere, to build an oil condensate terminal, then transferred to the Port of Corpus Christi Authority, administrator of the nation’s top port for oil exports, when it bought the land in 2021.

Since then, the Port has sought developers to build and operate a terminal in the space, the lawyers found, even though proposed layouts and environmental conditions differ greatly from the project plans reviewed for the 2016 permit.

In November, Sanchez and the other groups announced their campaign publicly when their lawyers filed official comments with USACE, requesting that the permit for the site be revoked or subject to new reviews.

The Port of Corpus Christi Authority did not respond to a request for comment.

“Cultural information and environmental conditions at the site have changed, necessitating new federal reviews and a new permit application,” the comments said. “Local residents and researchers have re-discovered an archaeological site in the project area, consisting of a former settlement that was thought to be lost and is of great importance to the Karankawa and Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribes.”

Still, the site faces a slim shot at preservation. First it would need to be flagged by the Texas Historical Commission. But the commissioners there are appointed by Gov. Greg Abbott, who has received $40 million in campaign contributions from the oil and gas industry since taking office.

Even then, preservation under the law means digging up artifacts and putting them in storage so the site can be cleared for development. Only under exceptional circumstances could it be protected in an undisturbed state.

Neither Abbott’s office nor the Texas Historical Commission responded to a request for comment.

Despite the odds, Sanchez dreams of making Donnel Point a place that people could visit to feel their ancestors’ presence and imagine the thousands of years that they fished from the bay. The fossil fuel industry is a towering opponent, but she’s used to it here. She plans to never give up.

“In this type of organizing you can lose hope really fast,” she said. “No one here has lost hope.”

Disclosure: H-E-B, Texas A&M University, Texas A&M University Press and Texas Historical Commission have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.