‘I Didn’t Vote for This’: A Revolt Against DOGE Cuts, Deep in Trump Country

The road to the tiny hamlet of Marion in northwest Montana is lined with the thick trees of the Flathead National Forest, with modern homesteads of trailers and modest homes dotting clearings here and there. Outside a timber frame café called the Hilltop Hitching Post, one of the only gathering spots for Marion’s population of less than 1,200, hunter Terry Zink pulled up in a dusty, well-used F-150 pickup and got out wearing a camo jacket against the early September chill, and a ball cap atop wire-rimmed glasses.Zink, 57, is a third-generation houndsman who hunts big game, including mountain lions and bears. He also owns an archery target business. He’s a rural Montanan whose way of life and livelihood depend on public lands.He led me into the Hilltop, where half the people inside knew his name, to a corner where we sat drinking diner coffee. “You won’t meet anyone more conservative than me, and I didn’t vote for this,” Zink said.“This” is the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) deep cuts earlier this year to federal public lands agencies’ funding, and to the staff at those agencies who administer that funding and steward public lands and wildlife.Zink voted for Trump but said he doesn’t agree with everything the president does. Zink clarifies he calls himself a “conservative” over calling himself a “Republican.” He doesn’t like Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric. “I prefer common sense in the middle,” he said.He believes wolves need to be hunted to manage their numbers; abortion should only be legal in cases of rape, incest and to protect the mother’s life; and he’s an ardent Second Amendment supporter. He’s also a passionate advocate for public lands and wildlife. And the cuts have, frankly, ticked him off.He is vocal not just about protecting public lands, but also about protecting the staff at those agencies. “We have to listen to our wildlife biologists. We have to be strong advocates for those people,” Zink said.Hunting season had yet to open when we spoke, but Zink was already hearing from fellow hunters who had to cut their own way into trails to hunting camps after Forest Service trail crews were laid off en masse. He worries about wildlife management with agency scientists also terminated.Zink’s story is just one example of how the DOGE cuts to public lands agencies are hitting rural, conservative communities — one of this administration’s strongest voting bases — the hardest. Starting in February, an estimated 5,200 people have been terminated from the agencies that manage the 640 million acres of federal public lands in the U.S. That number doesn’t include the many who took the administration’s buyout or early retirement offers also meant to cut staff. Further, Trump’s 2026 budget proposes more budget cuts and a reduction of nearly 18,500 more public lands employees.Much of the national spotlight has fallen on the impacts of these cuts to national parks, as that is the public lands model the majority of Americans are most familiar with: Yosemite, Yellowstone, Glacier, the Grand Canyon, to name just a few of the most iconic. In the rural West, though, federal public lands are more than just a scenic spot to take a family vacation once a year. These agencies are often the primary employers in the communities adjacent to public lands.Steve Ellis, chair of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees who was stationed in small towns in Oregon, Idaho, Nevada and Alaska, said that “the federal payroll from the BLM, the Forest Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service in these small rural communities is huge. It helps pay taxes. It helps keep the little hospital open. Federal employees have kids in the schools where the funding from the state depends on the number of students.” Hollow out the agencies, he said, and the communities themselves are hollowed out.In addition to the employees and their families who’ve been impacted, those staffing cuts are also affecting the ways of life and livelihoods that are major economic drivers out here for almost everyone else, too. Ranchers and farmers use public lands for agriculture; outfitters and guides take guests into them; hunters access them regularly to put food in the family freezer; and forestry, timber and sawmill workers fulfill contracts on them for wildfire mitigation and lumber.Trump won Montana by nearly 20 points in the 2024 election. Voters also ousted three-term Democratic Senator Jon Tester, a third-generation farmer from rural eastern Montana and the last legislator in the Senate who maintained a full-time job outside his political career, in favor of novice MAGA Republican Tim Sheehy. That race shattered spending records as Republicans went all in to flip the seat to win the Senate. For the first time in nearly a century, Montana — a famously purple state — went all red.But here, support for public lands is not a partisan issue. A 2024 poll of Montanans showed 95 percent of respondents had visited public lands in the last year, nearly half of them at least 10 times. The same poll showed 98 percent of Democrats, 84 percent of independents and 71 percent of Republicans said conservation issues are important to their voting decisions.Yet many national Republicans, including Trump, don’t seem to understand what a nonstarter cuts to public lands are for voters in Montana, and much of the rest of the rural West — even though, when Utah Republican Senator Mike Lee wrote a provision into Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill to sell off public lands to pay for tax cuts, Montana’s two Republican senators, followed by Idaho’s, led the outcry that got the proposal pulled. Out of all the controversial pieces of that bill, the public lands sale proposal was one of the few that made MAGA senators break from the party line. And public land sales are just the tip of the iceberg here.I spoke to people across Montana, from different professions and down the political range from independent to staunchly conservative, and they all agreed on a few things: They support adequately staffed public lands and continued public access to them; and with further cuts and rollbacks proposed at the same time people are beginning to personally feel the impacts of public lands attacks, policymakers are waking a political sleeping giant.“You cannot fire our firefighters. You cannot fire our trail crews. You have to have selective logging, and water restoration, and healthy forests,” Zink said. “People in Washington D.C., on the West Coast, East Coast — they don't understand what that means to us out here.”Dust billowed behind Denny Iverson’s pickup as he drove past the irrigation pivot on his ranchland in Montana’s Blackfoot River valley. He was only irrigating a small strip of grass for his cattle to graze later in the season. Montana was experiencing its worst drought in 50 years, and the river was as low as Iverson, 67, had ever seen it.He stopped the truck and gazed out at his fields from under the brim of a ball cap as worn as his jeans. The landscape here is beautiful, cupped as it is in federal public lands. The surrounding mountains are national forest, managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Much of the Blackfoot River is managed by the Bureau of Land Management.Iverson explained that most ranches in Montana have a base ranch with significant acreage, and then rely on nearby federal land or state land for summer pasture in what are called grazing allotments. His allotment is on BLM land in the mountains near the old mining town of Garnet, land he treats like his own, taking care not to overgraze it. A ranch this size, 700 private acres, could still operate without a public land allotment by leasing other private land, but that’s much more expensive — prohibitively so, for most ranchers. Down in the Southwest, he said, many ranches are a whopping 90 percent federal land allotments; it’s often much less than that in western Montana.“We’re trying to keep enough water in the river to keep the fish alive,” Iverson said. He’s part of the Blackfoot Challenge, a community group made up of landowners, public land agency partners and organizations that coordinate efforts to conserve the rural way of life and natural resources in the valley and administers federal funding to do so. “My hay production was at 60 percent this year. We’re in a terrible drought and getting assistance with that will be slow to come.”From January to May, the Blackfoot Challenge saw $4.6 million in already appropriated multi-year funds from federal public land agencies — including USFS, BLM and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — frozen. Those funds, which the Challenge receives directly and then uses to work on collaborative projects, went to “implement good water and irrigation practices, good weed management, good grazing practices,” and myriad other projects, Iverson said. Those included drought resilience and wildfire mitigation, which ranchers rely on to keep their lands healthy and their operations viable.Funding was also frozen for conservation easements, voluntary legal agreements between land owners and land trusts or public lands agencies that permanently protect the land for its working and conservation values while limiting development and subdivision. Those easements are a solution for ranchers and farmers who might otherwise struggle to keep their working land as its value soars in a rapidly gentrifying West. They also stitch together large landscapes for wildlife to travel as development pressure fragments old family ranches and farms. The frozen funds left many families in unintended debt.Montana’s congressional delegation does seem to be listening to voters somewhat; the Blackfoot Challenge has seen much of its funding unfrozen after calls, letters and congressional visits from landowners and other advocates.But in other ways, Republicans’ attacks on public lands seem to only be ramping up. In his 2026 budget, Trump proposed cutting a program called WaterSMART, which is administered through the Bureau of Reclamation and has historically provided millions for rural communities in Montana to address water security in a region where it is often scarce. And the U.S. House recently voted to throw out three huge public lands management plans, including one in eastern Montana. These plans had been developed over years with input from ranchers, farmers, tribes, agencies, energy companies and conservationists on how to use parcels of land and balance economic activities like oil and gas extraction and grazing with wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation. Instead, individual land use decisions would reroute through Congress — "people who don’t know the particulars of managing that land,” reported Montana Public Radio. Both Montana Republican Representatives, Troy Downing and Ryan Zinke, voted in favor, claiming it would unlock coal leasing in the Powder River basin.None of Montana’s congressional delegation — Senators Sheehy and Steve Daines, and Zinke and Downing — responded to multiple requests for comment for this story.“When programs get cut, when you lose staff ... ” Iverson trails off. “I’m worried about what this means in the long term, what it’s going to look like in the future.”Iverson is representative of Montana politics up until 2024, when the population was still small enough that it was possible to know national elected officials on a first-name basis — in fact, Iverson went to college with Zinke — and people often voted for the person rather than the party. “I’m pretty darn moderate, but I tend to lean conservative, vote Republican,” said Iverson. “But I never vote a straight-party ticket.”He voted for Trump — although he’s not a fan of Trump’s plan to lower beef prices and import Argentine meat, or Trump’s tariffs that are affecting fertilizer and fuel. He also voted for Tester, because “we worked with him a lot on conservation issues and other farm bill issues, and he was always responsive to folks in Montana.” Sheehy has to earn his trust, he says.When I asked Iverson if these cuts are affecting how he’ll vote, he said, “For me, it’s about, what are they doing for Montana? Are they advocating for conservation and farmers and ranchers, and the things I really care about?” He’s waiting for things on the ground to shake out.One of the other major sectors in rural Montana reeling from the cuts is forestry: a big umbrella that includes wildfire mitigation specialists, sawmill workers and other timber workers. I spoke to a forester in western Montana who owns a forestry business and employs a hand crew that does wildfire mitigation, thinning projects, service work on timber sales and tree planting. He was granted anonymity due to concerns for his business if he appeared in an article about politics.Like most people here who work on public land, he told me he doesn’t do it for the money; there’s not much money in it, anyway, belying the DOGE claims of significant cost saving to taxpayers as a whole. The four major public lands agencies — USFS, BLM, National Park Service, and FWS — had a combined total of $15.7 billion in government-appropriated funds in 2024. (For comparison, ICE’s newly expanded 2025 budget is $170 billion.) “I started in 1985 and I’m 57 now. I realized pretty early on, you're not going to get rich,” he said. “I just love to be in the woods. It gets into your blood.”When the cuts came down, they hit him hard. “Fifty percent of my income comes from federal dollars,” he said, some administered by groups like the Blackfoot Challenge, and some direct from public lands agencies that work with private contractors. He was out of work for a month in the spring due to the cuts. And it wasn’t just him losing out on income; he couldn’t pay his employees, either.“I wrote the senators and called, but I got no response, ever. I don’t want to have to go through this every year.” While some funds were unthawed and he was able to get to work, he says the uncertainty about the administration enacting more cuts is “nerve-wracking.” “The unknown of if I’m going to have contracts next year — it's very stressful. And then you’ve got to tell your employees what's going on, and they might be thinking about finding another job. I can't think of anything more stressful than not having a job that you're counting on.”Juanita Vero, Missoula County commissioner and fourth-generation owner of the E Bar L Guest Ranch, which is also part of the Blackfoot Challenge, confirms that as commissioner, she heard from a lot of people who were similarly affected. “These are folks who are skilled at working in the woods. … A lot of these guys were on a payment plan for buying equipment, ready to do this contracted work, and funds are frozen, and they can't do their work. They don't have a cushion. That was really scary and frustrating.”In March, Trump signed an executive order to increase logging on public lands. But DOGE cut many of the agency employees needed to administer the timber sales for logging, and for thinning and fire mitigation. If there’s no one to administer the sales, then private forestry contractors like the forester I spoke to can’t execute those projects. In addition, the U.S. no longer has the infrastructure to process the increased timber mandated by the executive order, and the government doesn’t appear to be investing in resurrecting it.When it comes to wildfire, the cuts represent a threat for entire rural counties. Ravalli County, which Trump won by 60 points (and is home to the famous ranch in the show Yellowstone), is surrounded by public lands. It’s frequently listed as one of the most at-risk counties in Montana, if not the entire West, for wildfires that consume properties and homes. In response to the cuts, the Ravalli County Collaborative, a group appointed by the county commissioners to promote the wise use of natural resources, pleaded with Montana’s congressional delegation to stand up to DOGE and re-staff the Bitterroot National Forest to mitigate wildfire — to no avail.Most people in Montana believe it’s only luck that the state didn’t see its usual major fire this year, or a big windstorm that decimates trails. Either of those would have exposed the new fragility of the agencies to respond to disaster, and even everyday maintenance needs — a fragility that many suspect may be intentional. Some worry that this administration’s cuts to public lands are a deliberate attempt to sabotage the system as an excuse to sell those lands for profit.“Hollowing out staffing, cutting budgets, changing priorities — all of that very much lends itself to the idea of essentially causing those agencies to fail at meeting their mandates, and that will lead to the call for privatization,” Sarah Lundstrum, Glacier program manager with the National Parks Conservation Association, told me for a story I reported for The Guardian on cuts that affected Glacier National Park. “Because if the government can't manage that land, then obviously somebody else should, right? In documents like Project 2025, there are calls for the privatization of land, or the sell-off of land.”In response, a representative from the Department of the Interior said that the DOI “is committed to stewarding America’s public lands and any suggestion that this Administration is seeking to sell them off is simply false ... Our mission remains to protect public lands, support rural livelihoods and ensure communities are more resilient in the face of increasing wildfire risk.”Many Montanans spoke sweepingly and passionately about the way of life here that has been created and sustained by public lands, and it’s clear those lands engender a value system around conservation and environmental stewardship that is unique to these regions. It’s indicative of a larger concern at play here: that this way of life itself, which is both rural and conservationist, is under threat because of continued attacks on public lands.Hunters, who rely on public lands, are some of the greatest conservationists in the state. They often help inform agency biologists of wildlife numbers on the ground. The group, including Zink, is responsible for rebounding mountain lions in the state by advocating for improved lion management. Nationally, hunters and anglers fund wildlife restoration, habitat improvement and land acquisition for conservation through a tax on hunting and angling equipment and licenses that sportsmen themselves lobbied for and helped pass. Zink regularly donates goods and dollars from his business to hunting organizations dedicated to protecting public lands and wildlife.To Zink, any political agenda that attacks public lands is a non-starter. He’s already watching wealthy people buy up land in Montana and close off access to adjacent public lands — or buying up a whole mountain range, in one case. “Both the rich and the poor get to use public lands. I believe every piece of public land in the West should be able to be accessed by public land hunters. The wildlife belongs to we the people.”That’s true even though 80 percent of the U.S. population lives east of the Mississippi River, while about 90 percent of all public land lies in Western states. But just because many Americans may not spend as much time in them, that doesn’t mean they should have less value to people in the East, says outfitter Jack Rich.Rich is one of more than 100 outfitters and guides who make up a major economic engine in the state; in 2024, outfitting and guiding brought in nearly $314 million to Montana. He owns the Rich Ranch, an outfitting and guest ranch outside Seeley on the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness, one of the largest wildernesses in the Lower 48. Rich — whose ancestors came to Montana before it was even named a territory — hosts guests at the ranch and takes people hiking, horseback riding, hunting, fishing and on pack trips. He speaks in the soaring oratorial style of famous outdoorsmen like John Muir and Bradford Washburn and sometimes falls into reciting poetry.“Outfitters play an incredible, vital role, which is sometimes underappreciated, in making sure that those people who don't have the skills and equipment can still enjoy America’s great outdoors — and in the process, become advocates for it in their own right,” he said. “We have a partner in that: the government. And the partnership only works if both partners work together for the same end goal, which is to care for the resources and serve the people.”Outfitters and guides have permits to operate on public lands and rely on agency staff to administer the permits, in addition to maintaining those lands, from wildlife habitat to trail clearing. As the DOGE cuts came down and trail crews were laid off, outfitters across the state, including Rich, have been obligated to clear more trails on their own, many without compensation for the labor. Rich also said that high-level USFS employees that he’d had longtime working relationships with — the regional forester, forest supervisor, and district ranger — all took the early retirement package the administration offered, gutting the institutional knowledge on the Flathead National Forest.Many Montanans I spoke to were all for more government efficiency and agreed that some “fat” needed to be trimmed, but that fat, they said, was most often in the middle management ranks. While hard numbers have been difficult to pin down, and the employees remaining at agencies often aren’t authorized to speak to media, the general sense from ex-employees and people working adjacent to the agencies is that the DOGE approach instead wiped out the upper ranks with institutional knowledge through buyout offers and early retirement packages — which means taxpayers are now paying for those ex-employees to do nothing rather saving the money DOGE touted. At the same time, the terminations targeting probationary and seasonal employees eliminated the next generation of public lands stewards. “It’s a pretty dismal way to do business,” Rich said.Most voters seem to be waiting to see how this administration’s cuts and policies, and the response to them from Montana’s congressional delegation, play out on the ground after court stays; essentially, they’re waiting to see what will stick. Daines is up for re-election in 2026. Although no Democrat has galvanized enough support to represent a real challenge and take advantage of this unrest around public lands, there is still time — especially since most agree that the ripple effects from the cuts, while people are already feeling them, have yet to fully hit.And it's only very recently that Montana shifted from a purple state to red. If national Republicans continue to make public lands a target of budget cuts, without understanding the unique politics of them in Western states like Montana, some suggest the party will likely have to face the wrath of these voters.“If we get poked too hard on this, they’re going to get primaried and voted out,” Zink said.A mostly Republican group of voters who are highly motivated by public lands has organized and caused an upset before. In 2018, midway through Trump’s first administration, which slashed national monuments and opened increased amounts of public land to resource extraction, hunters and anglers in Idaho and Wyoming voted down Republican gubernatorial candidates who attacked public lands in the Trump vein. Something similar could easily happen here. Montana is home to more hunters than Idaho or Wyoming — or any other Western state, for that matter — with more than three in five voters considering themselves a hunter or an angler.Rich, who’s registered Independent, recently took a retired senator and congressman, both of whom represented Eastern states, out into the Bob on horseback.“We were standing at a high mountain lake and I said, ‘Remember, the coolest thing is that this belongs to every American equally, whether you’re in New York City or Montana. We have the money and the technology to tame every single landscape. The reason we have wild places in their natural state is because we as a society have chosen that. If we no longer choose that, it will go away.’”“I think that if there is a place that can galvanize across the geopolitical spectrum, it's the treasure of our public lands, waters, wildlife and fisheries,” Rich said, “the things that we have that are uniquely American.”

Cassidy Randall is a freelance writer based in Montana.

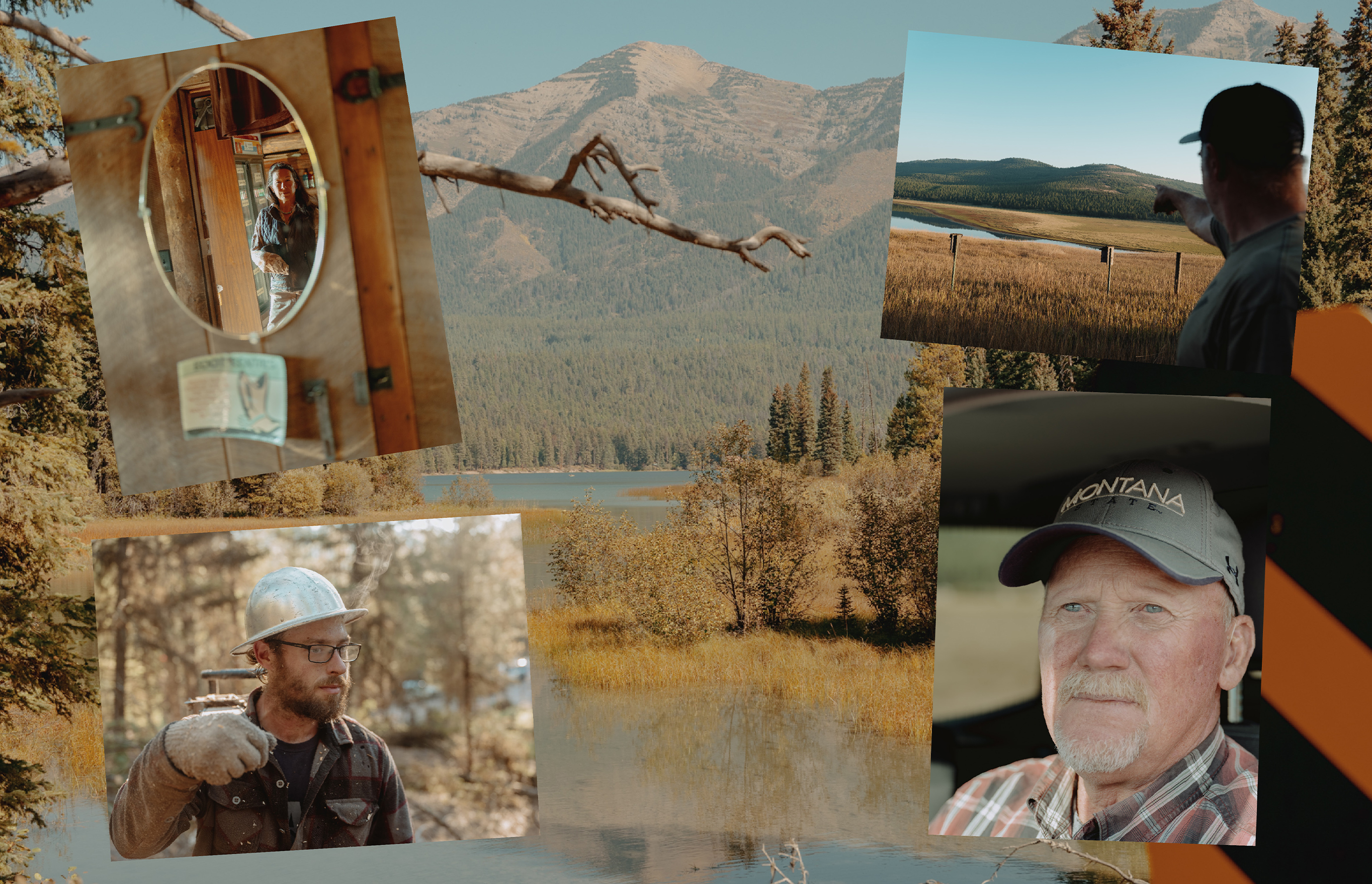

The road to the tiny hamlet of Marion in northwest Montana is lined with the thick trees of the Flathead National Forest, with modern homesteads of trailers and modest homes dotting clearings here and there. Outside a timber frame café called the Hilltop Hitching Post, one of the only gathering spots for Marion’s population of less than 1,200, hunter Terry Zink pulled up in a dusty, well-used F-150 pickup and got out wearing a camo jacket against the early September chill, and a ball cap atop wire-rimmed glasses.

Zink, 57, is a third-generation houndsman who hunts big game, including mountain lions and bears. He also owns an archery target business. He’s a rural Montanan whose way of life and livelihood depend on public lands.

He led me into the Hilltop, where half the people inside knew his name, to a corner where we sat drinking diner coffee. “You won’t meet anyone more conservative than me, and I didn’t vote for this,” Zink said.

“This” is the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) deep cuts earlier this year to federal public lands agencies’ funding, and to the staff at those agencies who administer that funding and steward public lands and wildlife.

Zink voted for Trump but said he doesn’t agree with everything the president does. Zink clarifies he calls himself a “conservative” over calling himself a “Republican.” He doesn’t like Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric. “I prefer common sense in the middle,” he said.

He believes wolves need to be hunted to manage their numbers; abortion should only be legal in cases of rape, incest and to protect the mother’s life; and he’s an ardent Second Amendment supporter. He’s also a passionate advocate for public lands and wildlife. And the cuts have, frankly, ticked him off.

He is vocal not just about protecting public lands, but also about protecting the staff at those agencies. “We have to listen to our wildlife biologists. We have to be strong advocates for those people,” Zink said.

Hunting season had yet to open when we spoke, but Zink was already hearing from fellow hunters who had to cut their own way into trails to hunting camps after Forest Service trail crews were laid off en masse. He worries about wildlife management with agency scientists also terminated.

Zink’s story is just one example of how the DOGE cuts to public lands agencies are hitting rural, conservative communities — one of this administration’s strongest voting bases — the hardest. Starting in February, an estimated 5,200 people have been terminated from the agencies that manage the 640 million acres of federal public lands in the U.S. That number doesn’t include the many who took the administration’s buyout or early retirement offers also meant to cut staff. Further, Trump’s 2026 budget proposes more budget cuts and a reduction of nearly 18,500 more public lands employees.

Much of the national spotlight has fallen on the impacts of these cuts to national parks, as that is the public lands model the majority of Americans are most familiar with: Yosemite, Yellowstone, Glacier, the Grand Canyon, to name just a few of the most iconic. In the rural West, though, federal public lands are more than just a scenic spot to take a family vacation once a year. These agencies are often the primary employers in the communities adjacent to public lands.

Steve Ellis, chair of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees who was stationed in small towns in Oregon, Idaho, Nevada and Alaska, said that “the federal payroll from the BLM, the Forest Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service in these small rural communities is huge. It helps pay taxes. It helps keep the little hospital open. Federal employees have kids in the schools where the funding from the state depends on the number of students.” Hollow out the agencies, he said, and the communities themselves are hollowed out.

In addition to the employees and their families who’ve been impacted, those staffing cuts are also affecting the ways of life and livelihoods that are major economic drivers out here for almost everyone else, too. Ranchers and farmers use public lands for agriculture; outfitters and guides take guests into them; hunters access them regularly to put food in the family freezer; and forestry, timber and sawmill workers fulfill contracts on them for wildfire mitigation and lumber.

Trump won Montana by nearly 20 points in the 2024 election. Voters also ousted three-term Democratic Senator Jon Tester, a third-generation farmer from rural eastern Montana and the last legislator in the Senate who maintained a full-time job outside his political career, in favor of novice MAGA Republican Tim Sheehy. That race shattered spending records as Republicans went all in to flip the seat to win the Senate. For the first time in nearly a century, Montana — a famously purple state — went all red.

But here, support for public lands is not a partisan issue. A 2024 poll of Montanans showed 95 percent of respondents had visited public lands in the last year, nearly half of them at least 10 times. The same poll showed 98 percent of Democrats, 84 percent of independents and 71 percent of Republicans said conservation issues are important to their voting decisions.

Yet many national Republicans, including Trump, don’t seem to understand what a nonstarter cuts to public lands are for voters in Montana, and much of the rest of the rural West — even though, when Utah Republican Senator Mike Lee wrote a provision into Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill to sell off public lands to pay for tax cuts, Montana’s two Republican senators, followed by Idaho’s, led the outcry that got the proposal pulled. Out of all the controversial pieces of that bill, the public lands sale proposal was one of the few that made MAGA senators break from the party line. And public land sales are just the tip of the iceberg here.

I spoke to people across Montana, from different professions and down the political range from independent to staunchly conservative, and they all agreed on a few things: They support adequately staffed public lands and continued public access to them; and with further cuts and rollbacks proposed at the same time people are beginning to personally feel the impacts of public lands attacks, policymakers are waking a political sleeping giant.

“You cannot fire our firefighters. You cannot fire our trail crews. You have to have selective logging, and water restoration, and healthy forests,” Zink said. “People in Washington D.C., on the West Coast, East Coast — they don't understand what that means to us out here.”

Dust billowed behind Denny Iverson’s pickup as he drove past the irrigation pivot on his ranchland in Montana’s Blackfoot River valley. He was only irrigating a small strip of grass for his cattle to graze later in the season. Montana was experiencing its worst drought in 50 years, and the river was as low as Iverson, 67, had ever seen it.

He stopped the truck and gazed out at his fields from under the brim of a ball cap as worn as his jeans. The landscape here is beautiful, cupped as it is in federal public lands. The surrounding mountains are national forest, managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Much of the Blackfoot River is managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

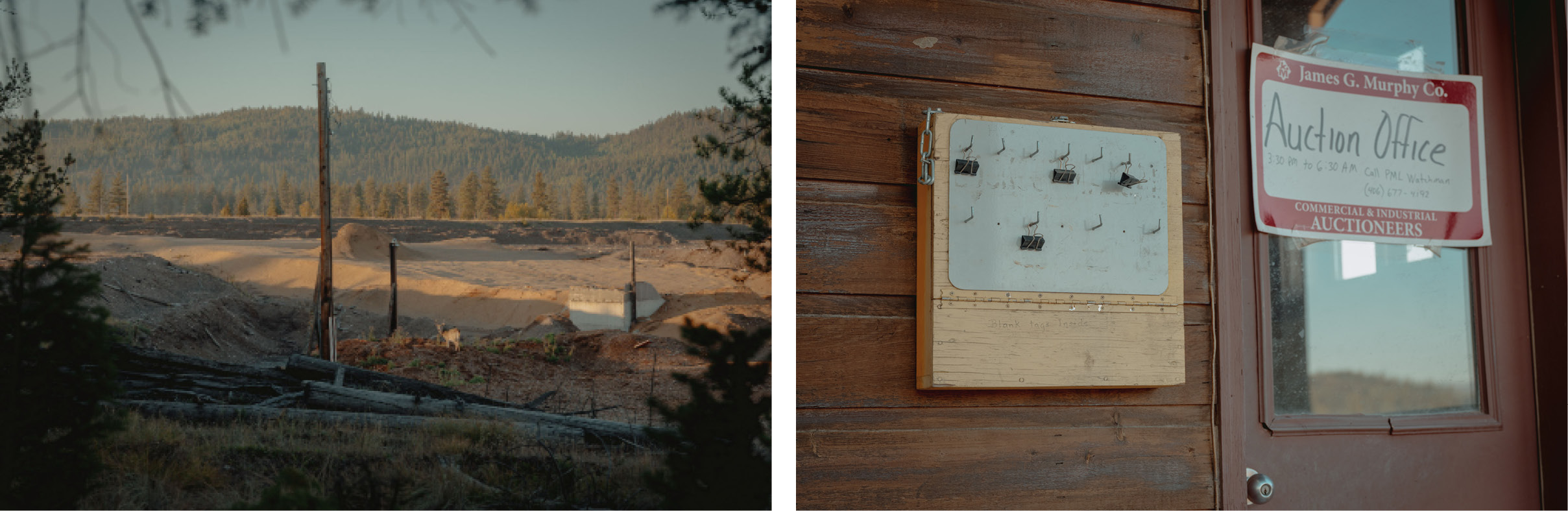

Iverson explained that most ranches in Montana have a base ranch with significant acreage, and then rely on nearby federal land or state land for summer pasture in what are called grazing allotments. His allotment is on BLM land in the mountains near the old mining town of Garnet, land he treats like his own, taking care not to overgraze it. A ranch this size, 700 private acres, could still operate without a public land allotment by leasing other private land, but that’s much more expensive — prohibitively so, for most ranchers. Down in the Southwest, he said, many ranches are a whopping 90 percent federal land allotments; it’s often much less than that in western Montana.

“We’re trying to keep enough water in the river to keep the fish alive,” Iverson said. He’s part of the Blackfoot Challenge, a community group made up of landowners, public land agency partners and organizations that coordinate efforts to conserve the rural way of life and natural resources in the valley and administers federal funding to do so. “My hay production was at 60 percent this year. We’re in a terrible drought and getting assistance with that will be slow to come.”

From January to May, the Blackfoot Challenge saw $4.6 million in already appropriated multi-year funds from federal public land agencies — including USFS, BLM and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — frozen. Those funds, which the Challenge receives directly and then uses to work on collaborative projects, went to “implement good water and irrigation practices, good weed management, good grazing practices,” and myriad other projects, Iverson said. Those included drought resilience and wildfire mitigation, which ranchers rely on to keep their lands healthy and their operations viable.

Funding was also frozen for conservation easements, voluntary legal agreements between land owners and land trusts or public lands agencies that permanently protect the land for its working and conservation values while limiting development and subdivision. Those easements are a solution for ranchers and farmers who might otherwise struggle to keep their working land as its value soars in a rapidly gentrifying West. They also stitch together large landscapes for wildlife to travel as development pressure fragments old family ranches and farms. The frozen funds left many families in unintended debt.

Montana’s congressional delegation does seem to be listening to voters somewhat; the Blackfoot Challenge has seen much of its funding unfrozen after calls, letters and congressional visits from landowners and other advocates.

But in other ways, Republicans’ attacks on public lands seem to only be ramping up. In his 2026 budget, Trump proposed cutting a program called WaterSMART, which is administered through the Bureau of Reclamation and has historically provided millions for rural communities in Montana to address water security in a region where it is often scarce. And the U.S. House recently voted to throw out three huge public lands management plans, including one in eastern Montana. These plans had been developed over years with input from ranchers, farmers, tribes, agencies, energy companies and conservationists on how to use parcels of land and balance economic activities like oil and gas extraction and grazing with wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation. Instead, individual land use decisions would reroute through Congress — "people who don’t know the particulars of managing that land,” reported Montana Public Radio. Both Montana Republican Representatives, Troy Downing and Ryan Zinke, voted in favor, claiming it would unlock coal leasing in the Powder River basin.

None of Montana’s congressional delegation — Senators Sheehy and Steve Daines, and Zinke and Downing — responded to multiple requests for comment for this story.

“When programs get cut, when you lose staff ... ” Iverson trails off. “I’m worried about what this means in the long term, what it’s going to look like in the future.”

Iverson is representative of Montana politics up until 2024, when the population was still small enough that it was possible to know national elected officials on a first-name basis — in fact, Iverson went to college with Zinke — and people often voted for the person rather than the party. “I’m pretty darn moderate, but I tend to lean conservative, vote Republican,” said Iverson. “But I never vote a straight-party ticket.”

He voted for Trump — although he’s not a fan of Trump’s plan to lower beef prices and import Argentine meat, or Trump’s tariffs that are affecting fertilizer and fuel. He also voted for Tester, because “we worked with him a lot on conservation issues and other farm bill issues, and he was always responsive to folks in Montana.” Sheehy has to earn his trust, he says.

When I asked Iverson if these cuts are affecting how he’ll vote, he said, “For me, it’s about, what are they doing for Montana? Are they advocating for conservation and farmers and ranchers, and the things I really care about?” He’s waiting for things on the ground to shake out.

One of the other major sectors in rural Montana reeling from the cuts is forestry: a big umbrella that includes wildfire mitigation specialists, sawmill workers and other timber workers. I spoke to a forester in western Montana who owns a forestry business and employs a hand crew that does wildfire mitigation, thinning projects, service work on timber sales and tree planting. He was granted anonymity due to concerns for his business if he appeared in an article about politics.

Like most people here who work on public land, he told me he doesn’t do it for the money; there’s not much money in it, anyway, belying the DOGE claims of significant cost saving to taxpayers as a whole. The four major public lands agencies — USFS, BLM, National Park Service, and FWS — had a combined total of $15.7 billion in government-appropriated funds in 2024. (For comparison, ICE’s newly expanded 2025 budget is $170 billion.) “I started in 1985 and I’m 57 now. I realized pretty early on, you're not going to get rich,” he said. “I just love to be in the woods. It gets into your blood.”

When the cuts came down, they hit him hard. “Fifty percent of my income comes from federal dollars,” he said, some administered by groups like the Blackfoot Challenge, and some direct from public lands agencies that work with private contractors. He was out of work for a month in the spring due to the cuts. And it wasn’t just him losing out on income; he couldn’t pay his employees, either.

“I wrote the senators and called, but I got no response, ever. I don’t want to have to go through this every year.” While some funds were unthawed and he was able to get to work, he says the uncertainty about the administration enacting more cuts is “nerve-wracking.” “The unknown of if I’m going to have contracts next year — it's very stressful. And then you’ve got to tell your employees what's going on, and they might be thinking about finding another job. I can't think of anything more stressful than not having a job that you're counting on.”

Juanita Vero, Missoula County commissioner and fourth-generation owner of the E Bar L Guest Ranch, which is also part of the Blackfoot Challenge, confirms that as commissioner, she heard from a lot of people who were similarly affected. “These are folks who are skilled at working in the woods. … A lot of these guys were on a payment plan for buying equipment, ready to do this contracted work, and funds are frozen, and they can't do their work. They don't have a cushion. That was really scary and frustrating.”

In March, Trump signed an executive order to increase logging on public lands. But DOGE cut many of the agency employees needed to administer the timber sales for logging, and for thinning and fire mitigation. If there’s no one to administer the sales, then private forestry contractors like the forester I spoke to can’t execute those projects. In addition, the U.S. no longer has the infrastructure to process the increased timber mandated by the executive order, and the government doesn’t appear to be investing in resurrecting it.

When it comes to wildfire, the cuts represent a threat for entire rural counties. Ravalli County, which Trump won by 60 points (and is home to the famous ranch in the show Yellowstone), is surrounded by public lands. It’s frequently listed as one of the most at-risk counties in Montana, if not the entire West, for wildfires that consume properties and homes. In response to the cuts, the Ravalli County Collaborative, a group appointed by the county commissioners to promote the wise use of natural resources, pleaded with Montana’s congressional delegation to stand up to DOGE and re-staff the Bitterroot National Forest to mitigate wildfire — to no avail.

Most people in Montana believe it’s only luck that the state didn’t see its usual major fire this year, or a big windstorm that decimates trails. Either of those would have exposed the new fragility of the agencies to respond to disaster, and even everyday maintenance needs — a fragility that many suspect may be intentional. Some worry that this administration’s cuts to public lands are a deliberate attempt to sabotage the system as an excuse to sell those lands for profit.

“Hollowing out staffing, cutting budgets, changing priorities — all of that very much lends itself to the idea of essentially causing those agencies to fail at meeting their mandates, and that will lead to the call for privatization,” Sarah Lundstrum, Glacier program manager with the National Parks Conservation Association, told me for a story I reported for The Guardian on cuts that affected Glacier National Park. “Because if the government can't manage that land, then obviously somebody else should, right? In documents like Project 2025, there are calls for the privatization of land, or the sell-off of land.”

In response, a representative from the Department of the Interior said that the DOI “is committed to stewarding America’s public lands and any suggestion that this Administration is seeking to sell them off is simply false ... Our mission remains to protect public lands, support rural livelihoods and ensure communities are more resilient in the face of increasing wildfire risk.”

Many Montanans spoke sweepingly and passionately about the way of life here that has been created and sustained by public lands, and it’s clear those lands engender a value system around conservation and environmental stewardship that is unique to these regions. It’s indicative of a larger concern at play here: that this way of life itself, which is both rural and conservationist, is under threat because of continued attacks on public lands.

Hunters, who rely on public lands, are some of the greatest conservationists in the state. They often help inform agency biologists of wildlife numbers on the ground. The group, including Zink, is responsible for rebounding mountain lions in the state by advocating for improved lion management. Nationally, hunters and anglers fund wildlife restoration, habitat improvement and land acquisition for conservation through a tax on hunting and angling equipment and licenses that sportsmen themselves lobbied for and helped pass. Zink regularly donates goods and dollars from his business to hunting organizations dedicated to protecting public lands and wildlife.

To Zink, any political agenda that attacks public lands is a non-starter. He’s already watching wealthy people buy up land in Montana and close off access to adjacent public lands — or buying up a whole mountain range, in one case. “Both the rich and the poor get to use public lands. I believe every piece of public land in the West should be able to be accessed by public land hunters. The wildlife belongs to we the people.”

That’s true even though 80 percent of the U.S. population lives east of the Mississippi River, while about 90 percent of all public land lies in Western states. But just because many Americans may not spend as much time in them, that doesn’t mean they should have less value to people in the East, says outfitter Jack Rich.

Rich is one of more than 100 outfitters and guides who make up a major economic engine in the state; in 2024, outfitting and guiding brought in nearly $314 million to Montana. He owns the Rich Ranch, an outfitting and guest ranch outside Seeley on the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness, one of the largest wildernesses in the Lower 48. Rich — whose ancestors came to Montana before it was even named a territory — hosts guests at the ranch and takes people hiking, horseback riding, hunting, fishing and on pack trips. He speaks in the soaring oratorial style of famous outdoorsmen like John Muir and Bradford Washburn and sometimes falls into reciting poetry.

“Outfitters play an incredible, vital role, which is sometimes underappreciated, in making sure that those people who don't have the skills and equipment can still enjoy America’s great outdoors — and in the process, become advocates for it in their own right,” he said. “We have a partner in that: the government. And the partnership only works if both partners work together for the same end goal, which is to care for the resources and serve the people.”

Outfitters and guides have permits to operate on public lands and rely on agency staff to administer the permits, in addition to maintaining those lands, from wildlife habitat to trail clearing. As the DOGE cuts came down and trail crews were laid off, outfitters across the state, including Rich, have been obligated to clear more trails on their own, many without compensation for the labor. Rich also said that high-level USFS employees that he’d had longtime working relationships with — the regional forester, forest supervisor, and district ranger — all took the early retirement package the administration offered, gutting the institutional knowledge on the Flathead National Forest.

Many Montanans I spoke to were all for more government efficiency and agreed that some “fat” needed to be trimmed, but that fat, they said, was most often in the middle management ranks. While hard numbers have been difficult to pin down, and the employees remaining at agencies often aren’t authorized to speak to media, the general sense from ex-employees and people working adjacent to the agencies is that the DOGE approach instead wiped out the upper ranks with institutional knowledge through buyout offers and early retirement packages — which means taxpayers are now paying for those ex-employees to do nothing rather saving the money DOGE touted. At the same time, the terminations targeting probationary and seasonal employees eliminated the next generation of public lands stewards. “It’s a pretty dismal way to do business,” Rich said.

Most voters seem to be waiting to see how this administration’s cuts and policies, and the response to them from Montana’s congressional delegation, play out on the ground after court stays; essentially, they’re waiting to see what will stick. Daines is up for re-election in 2026. Although no Democrat has galvanized enough support to represent a real challenge and take advantage of this unrest around public lands, there is still time — especially since most agree that the ripple effects from the cuts, while people are already feeling them, have yet to fully hit.

And it's only very recently that Montana shifted from a purple state to red. If national Republicans continue to make public lands a target of budget cuts, without understanding the unique politics of them in Western states like Montana, some suggest the party will likely have to face the wrath of these voters.

“If we get poked too hard on this, they’re going to get primaried and voted out,” Zink said.

A mostly Republican group of voters who are highly motivated by public lands has organized and caused an upset before. In 2018, midway through Trump’s first administration, which slashed national monuments and opened increased amounts of public land to resource extraction, hunters and anglers in Idaho and Wyoming voted down Republican gubernatorial candidates who attacked public lands in the Trump vein. Something similar could easily happen here. Montana is home to more hunters than Idaho or Wyoming — or any other Western state, for that matter — with more than three in five voters considering themselves a hunter or an angler.

Rich, who’s registered Independent, recently took a retired senator and congressman, both of whom represented Eastern states, out into the Bob on horseback.

“We were standing at a high mountain lake and I said, ‘Remember, the coolest thing is that this belongs to every American equally, whether you’re in New York City or Montana. We have the money and the technology to tame every single landscape. The reason we have wild places in their natural state is because we as a society have chosen that. If we no longer choose that, it will go away.’”

“I think that if there is a place that can galvanize across the geopolitical spectrum, it's the treasure of our public lands, waters, wildlife and fisheries,” Rich said, “the things that we have that are uniquely American.”