How a Trove of Whaling Logbooks Will Help Scientists Understand Our Changing Climate

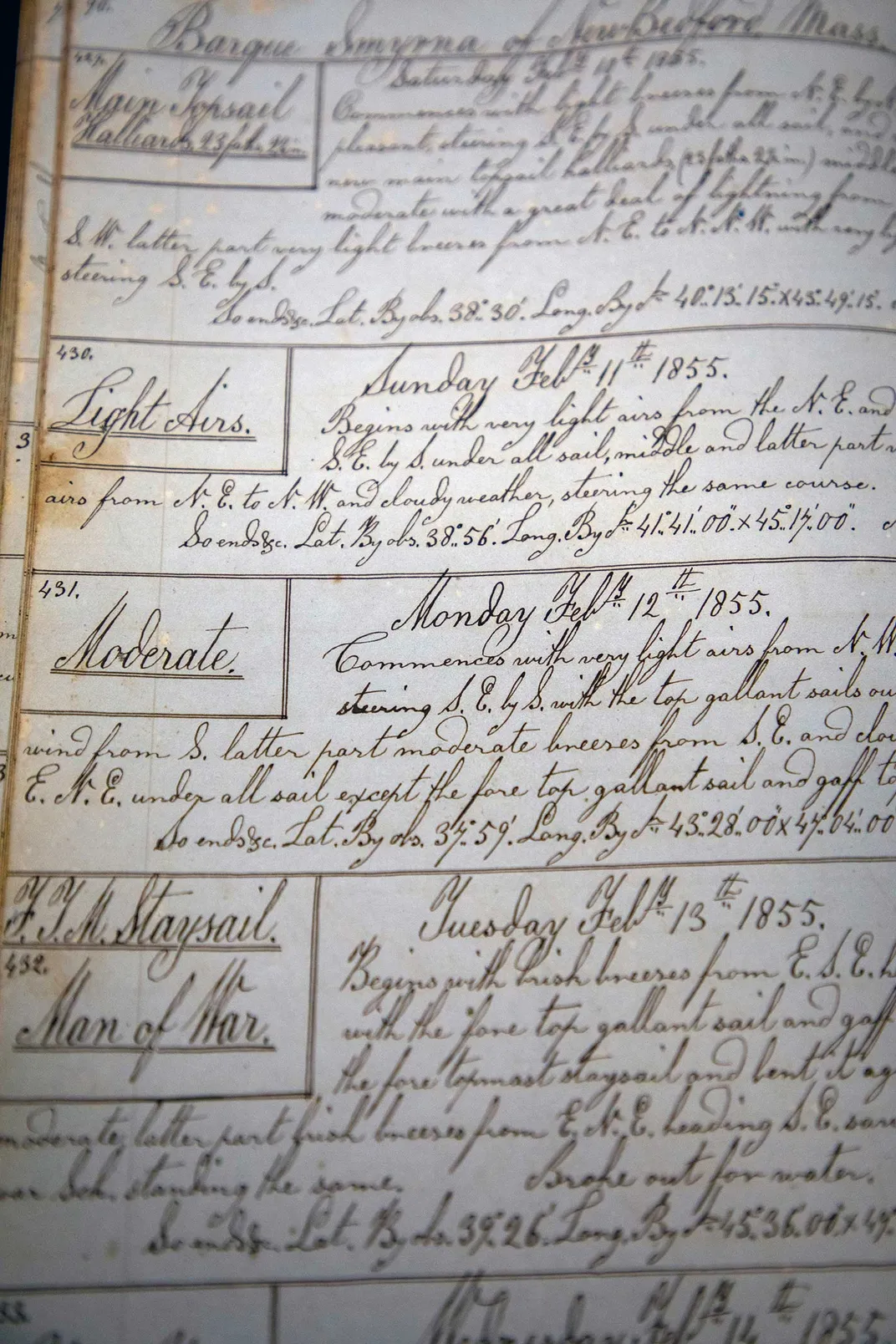

When the U.S. whaling industry was at its peak in the middle of the 19th century, crews relied heavily on the wind. Oil derived from captured whales helped power the machinery of the Industrial Revolution, but steam engines weren’t yet widely in use at sea. Only gusts and currents could propel these salty sailors to their prey and potential riches. Captains and crew members thus kept metronomic records of the wind as they chased whales across the world’s oceans. With little instrumental data available, subjective observations—a “light breeze,” a “strong gale”—often led logbook entries. The descriptions weren’t nearly as compelling as the narratives of skirmishes and illustrations of whales and ships that sometimes shared those pages. But these dry weather reports from the distant past now have their own dramatic significance: They’re helping scientists assess how the climate has changed in some of the most remote parts of the world. Analyzing a trove of 4,200 logbooks from New England whaling vessels, a group of researchers in New England has begun turning all those qualitative descriptions into quantitative data. Using the Beaufort Wind Scale, which was created in 1805 by a British admiral and assigns wind speeds to descriptive terms, they’re confident that those seemingly unscientific mentions of, say, light breezes, often correspond to relatively consistent ranges of wind strength. Through these translations and comparisons with modern instrumental data, they’re learning about how global wind patterns have shifted since U.S. whaling’s heyday in the 18th and 19th centuries. “I wasn’t entirely sure whether it would work,” says Caroline Ummenhofer, a physical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Falmouth, Massachusetts, and a co-author of a paper on the project in the journal Mainsheet. “What we have seen now is that, actually, it works better than we expected.” This logbook from the Smyrna, a New Bedford, Massachusetts, bark that sailed in the Indian Ocean during the 1850s, contains typical descriptions of the wind (“moderate,” “light”) that researchers can then translate into numbers using the Beaufort Wind Scale. Jayne Doucette © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution The researchers are still in the early stages of combing through millions of entries, but their findings thus far have often aligned with digital re-analysis products that use data to estimate past weather, including the wind. “That gives us more confidence, because they are completely independent,” Ummenhofer says. “None of the whaler data goes into this atmospheric re-analysis.” She hopes these records will be incorporated eventually. The re-analysis products use observations to tweak their models, but they’re missing long-term historical data from areas of the ocean where military and merchant marine ships didn’t travel. The logbooks from New England can help fill some of those gaps. During hunts, whaling vessels diverged from established sea lanes, venturing into parts of the world’s oceans where little observational data exists as they followed right, sperm and humpback whales, among others. “They’re going to places where other ships have no reason to go, and they’re recording the weather data. So that data that they have, scientifically speaking, is pretty much gold,” says Timothy Walker, a maritime and early modern European historian at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and a co-author of the Mainsheet paper. The focus on voyages through little-trafficked areas of the world’s oceans—including one in particular—distinguishes this project from past analyses of whaling logbook records. “This is not totally new research. Ship logs have been examined before to reconstruct weather and climate in the Pacific and in the Atlantic, but not so far in the Indian Ocean,” says Alexander Gershunov, a research meteorologist at the University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography who isn’t involved with the project. Logbook analysis belongs to the burgeoning interdisciplinary field of historical climatology. While paleoclimatologists have long examined environmental sources, such as tree rings and sediment deposits, to learn more about past climates, the study of artifacts and documents to do so is still gaining acceptance. “I think we’re getting better as a community to recognize the value of this unconventional data,” Ummenhofer says. Scientists have previously discovered, for example, that a strong belt of westerly winds known to mariners as the “Roaring Forties”—referring to the latitudes between 40 and 50 degrees south of the equator—has moved farther south toward Antarctica. Those winds bring critical rain-bearing weather systems with them and leave southern Africa and Australia more prone to droughts. But with few landmasses in that latitudinal range to site meteorological stations, scientists don’t have instrumental data to determine when, exactly, that shift in the wind began. Satellites weren’t invented until the middle of the 20th century, so the broader historical context for this phenomenon has been absent. Whaling records will clarify where ships encountered the strongest westerlies in the Southern Ocean and how they varied from year to year and decade to decade, Ummenhofer says. They’ll also shed more light on how trade winds in the tropical Pacific varied before the 1900s and how the strength and timing of the monsoon in the Indian Ocean has changed over the past 250 years. “They’re going to be able to reconstruct not just climate variability, but actual weather events and severe weather over the ocean back to the middle of the 18th century, way before instrumental data was broadly available,” says Gershunov. When they discover novel weather events, Gershunov says, the team should check them against environmental clues to see if they’re reflected in the natural world. He thinks the group’s findings will be superior to many “proxy” reconstructions that rely wholly on nature’s response to weather, rather than the weather itself, to draw conclusions about the past. “They’re based on notes taken by trained professionals who were specifically observing the ocean and the weather in a systematic and regular way,” he says. Ummenhofer had been working with environmental archives, including corals and stalagmites, when Walker contacted her several years ago about a human-centric one. He’d started working with the New Bedford Whaling Museum and realized its “extraordinary riches”—about 2,500 whaling logbooks, the largest collection in the world. A few blocks away in the city forever linked to Moby-Dick, the New Bedford Free Public Library housed around 500 of its own, and the Providence Public Library, Mystic Seaport Museum and Nantucket Historical Association also had hundreds stashed in each of their archives. Walker had spent time in graduate school sailing and knew these logbooks—the most important document carried on a ship, as insurance claims depended on its contents—would contain weather data of great interest to an ocean climate scientist like Ummenhofer. “Within about five minutes of chatting with her, her eyes lit up,” Walker recalls. Entries include information about geographic coordinates, temperature, precipitation and the wind. “There’s just no end to the richness that can be found in these records,” Walker says. Critically, by the late 1700s, these accounts had become increasingly systematic about tracking wind’s direction and force, according to Walker, mirroring the practices of European navies and other vessels to reach their targets more efficiently. With the widespread adoption of the Beaufort Wind Scale shortly thereafter, the mention of a “moderate breeze,” for example, could reliably mean that there were small waves, many whitecaps and wind gusting in the neighborhood of 13 to 18 miles per hour. Machines can’t read this yellowed, paleographic writing. So, with funding fits and starts, Walker and a team of student researchers have pored over the logbooks and documented the descriptions themselves. Sometimes the researchers have to make a judgment call when language differs slightly from the Beaufort Wind Scale. But they’re checking the precision of the entries by noting when two whaling ships crossed paths at sea during “gams,” then examining the ships’ separate observations of the area’s weather. “I don’t think we will ever get to the point where we can say, ‘This whaler on the 5th of January, 1822, in this spot in the Southern Ocean, experienced 3.52 meters per second [of wind],’” Ummenhofer says. “But I don’t think we need to to be able to really say something about shifting wind patterns.” Gershunov says some scientists may object to extrapolating too much from the logbooks, but he believes the researchers’ methods are sound due to the consistency of the records. “Even though they’re qualitative, they were made in a certain system that lends itself to quantification,” he says. Machines can’t yet read the yellowed paleography in logbooks, so researchers must scour pages for information about the wind’s direction and force, as well as other notes on the weather, and enter them manually into a database. Jayne Doucette © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Rainfall, the team’s next focus, will be more challenging than wind to quantify, Ummenhofer acknowledges. Captains and crew members often based their observations on personal experiences rather than a standard measure. But researchers can glean something from mere mentions of precipitation, Ummenhofer says, similar to how scientists with the Old Weather project used historical logbooks to chronicle the presence of sea ice in the Arctic. For now, Walker’s researchers are recording any weather-related data they can find. But sometimes they get distracted from the task at hand. Within the entries, “there’s no shortage of drama,” Walker says, with allusions to shipmates engaging in sexual activity with each other and narratives of men jumping ship and brawling. On the Atlantic, a ship that left New Bedford for the Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean in 1865, an African American cook stabbed a sailor of European descent to death, saying the seafarer had called him a racial slur. The cook was transferred to a different boat and tried in the U.S. for murder. But the Atlantic’s trials weren’t through: Another ship rammed into it in the middle of the night, destroying its head rig, among other parts. It barely made it back from the depths of the Indian Ocean to a port in Mauritius after the collision. A decade later, after lengthy, costly repairs, a third of its crew wouldn’t make it back from sea at all after two of its smaller hunting boats went missing while searching for whales in a storm. Whales figure prominently in the logbooks, too. In the margins, whalers depicted their captures with detailed illustrations; when they sighted an animal but didn’t catch it, whalers only drew its tail. Their prey could have helped sequester the rising carbon emissions from the Industrial Revolution. Like trees, whales store carbon, and when they die, that carbon sinks along with their carcasses to the ocean floor. The U.S. whaling industry, which faded by the 1920s, disrupted this natural cycle. But by merely documenting their experiences in unfamiliar waters, whalers have unwittingly allowed generations later to learn more about how the climate is changing. “I find that quite awe-inspiring, to be able to say, ‘Wow, there was someone 250 years ago, describing something about the weather conditions, definitely not knowing what this could be used for down the track,’” Ummenhofer says. “I think that that’s pretty amazing.” Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Researchers are examining more than 4,200 New England documents to turn descriptions of the wind into data

When the U.S. whaling industry was at its peak in the middle of the 19th century, crews relied heavily on the wind. Oil derived from captured whales helped power the machinery of the Industrial Revolution, but steam engines weren’t yet widely in use at sea. Only gusts and currents could propel these salty sailors to their prey and potential riches.

Captains and crew members thus kept metronomic records of the wind as they chased whales across the world’s oceans. With little instrumental data available, subjective observations—a “light breeze,” a “strong gale”—often led logbook entries. The descriptions weren’t nearly as compelling as the narratives of skirmishes and illustrations of whales and ships that sometimes shared those pages.

But these dry weather reports from the distant past now have their own dramatic significance: They’re helping scientists assess how the climate has changed in some of the most remote parts of the world.

Analyzing a trove of 4,200 logbooks from New England whaling vessels, a group of researchers in New England has begun turning all those qualitative descriptions into quantitative data. Using the Beaufort Wind Scale, which was created in 1805 by a British admiral and assigns wind speeds to descriptive terms, they’re confident that those seemingly unscientific mentions of, say, light breezes, often correspond to relatively consistent ranges of wind strength. Through these translations and comparisons with modern instrumental data, they’re learning about how global wind patterns have shifted since U.S. whaling’s heyday in the 18th and 19th centuries.

“I wasn’t entirely sure whether it would work,” says Caroline Ummenhofer, a physical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Falmouth, Massachusetts, and a co-author of a paper on the project in the journal Mainsheet. “What we have seen now is that, actually, it works better than we expected.”

The researchers are still in the early stages of combing through millions of entries, but their findings thus far have often aligned with digital re-analysis products that use data to estimate past weather, including the wind. “That gives us more confidence, because they are completely independent,” Ummenhofer says. “None of the whaler data goes into this atmospheric re-analysis.”

She hopes these records will be incorporated eventually. The re-analysis products use observations to tweak their models, but they’re missing long-term historical data from areas of the ocean where military and merchant marine ships didn’t travel. The logbooks from New England can help fill some of those gaps. During hunts, whaling vessels diverged from established sea lanes, venturing into parts of the world’s oceans where little observational data exists as they followed right, sperm and humpback whales, among others.

“They’re going to places where other ships have no reason to go, and they’re recording the weather data. So that data that they have, scientifically speaking, is pretty much gold,” says Timothy Walker, a maritime and early modern European historian at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and a co-author of the Mainsheet paper.

The focus on voyages through little-trafficked areas of the world’s oceans—including one in particular—distinguishes this project from past analyses of whaling logbook records.

“This is not totally new research. Ship logs have been examined before to reconstruct weather and climate in the Pacific and in the Atlantic, but not so far in the Indian Ocean,” says Alexander Gershunov, a research meteorologist at the University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography who isn’t involved with the project.

Logbook analysis belongs to the burgeoning interdisciplinary field of historical climatology. While paleoclimatologists have long examined environmental sources, such as tree rings and sediment deposits, to learn more about past climates, the study of artifacts and documents to do so is still gaining acceptance.

“I think we’re getting better as a community to recognize the value of this unconventional data,” Ummenhofer says.

Scientists have previously discovered, for example, that a strong belt of westerly winds known to mariners as the “Roaring Forties”—referring to the latitudes between 40 and 50 degrees south of the equator—has moved farther south toward Antarctica. Those winds bring critical rain-bearing weather systems with them and leave southern Africa and Australia more prone to droughts. But with few landmasses in that latitudinal range to site meteorological stations, scientists don’t have instrumental data to determine when, exactly, that shift in the wind began. Satellites weren’t invented until the middle of the 20th century, so the broader historical context for this phenomenon has been absent.

Whaling records will clarify where ships encountered the strongest westerlies in the Southern Ocean and how they varied from year to year and decade to decade, Ummenhofer says. They’ll also shed more light on how trade winds in the tropical Pacific varied before the 1900s and how the strength and timing of the monsoon in the Indian Ocean has changed over the past 250 years.

“They’re going to be able to reconstruct not just climate variability, but actual weather events and severe weather over the ocean back to the middle of the 18th century, way before instrumental data was broadly available,” says Gershunov.

When they discover novel weather events, Gershunov says, the team should check them against environmental clues to see if they’re reflected in the natural world. He thinks the group’s findings will be superior to many “proxy” reconstructions that rely wholly on nature’s response to weather, rather than the weather itself, to draw conclusions about the past.

“They’re based on notes taken by trained professionals who were specifically observing the ocean and the weather in a systematic and regular way,” he says.

Ummenhofer had been working with environmental archives, including corals and stalagmites, when Walker contacted her several years ago about a human-centric one. He’d started working with the New Bedford Whaling Museum and realized its “extraordinary riches”—about 2,500 whaling logbooks, the largest collection in the world. A few blocks away in the city forever linked to Moby-Dick, the New Bedford Free Public Library housed around 500 of its own, and the Providence Public Library, Mystic Seaport Museum and Nantucket Historical Association also had hundreds stashed in each of their archives.

Walker had spent time in graduate school sailing and knew these logbooks—the most important document carried on a ship, as insurance claims depended on its contents—would contain weather data of great interest to an ocean climate scientist like Ummenhofer. “Within about five minutes of chatting with her, her eyes lit up,” Walker recalls. Entries include information about geographic coordinates, temperature, precipitation and the wind.

“There’s just no end to the richness that can be found in these records,” Walker says.

Critically, by the late 1700s, these accounts had become increasingly systematic about tracking wind’s direction and force, according to Walker, mirroring the practices of European navies and other vessels to reach their targets more efficiently. With the widespread adoption of the Beaufort Wind Scale shortly thereafter, the mention of a “moderate breeze,” for example, could reliably mean that there were small waves, many whitecaps and wind gusting in the neighborhood of 13 to 18 miles per hour.

Machines can’t read this yellowed, paleographic writing. So, with funding fits and starts, Walker and a team of student researchers have pored over the logbooks and documented the descriptions themselves. Sometimes the researchers have to make a judgment call when language differs slightly from the Beaufort Wind Scale. But they’re checking the precision of the entries by noting when two whaling ships crossed paths at sea during “gams,” then examining the ships’ separate observations of the area’s weather.

“I don’t think we will ever get to the point where we can say, ‘This whaler on the 5th of January, 1822, in this spot in the Southern Ocean, experienced 3.52 meters per second [of wind],’” Ummenhofer says. “But I don’t think we need to to be able to really say something about shifting wind patterns.”

Gershunov says some scientists may object to extrapolating too much from the logbooks, but he believes the researchers’ methods are sound due to the consistency of the records.

“Even though they’re qualitative, they were made in a certain system that lends itself to quantification,” he says.

Rainfall, the team’s next focus, will be more challenging than wind to quantify, Ummenhofer acknowledges. Captains and crew members often based their observations on personal experiences rather than a standard measure. But researchers can glean something from mere mentions of precipitation, Ummenhofer says, similar to how scientists with the Old Weather project used historical logbooks to chronicle the presence of sea ice in the Arctic.

For now, Walker’s researchers are recording any weather-related data they can find. But sometimes they get distracted from the task at hand. Within the entries, “there’s no shortage of drama,” Walker says, with allusions to shipmates engaging in sexual activity with each other and narratives of men jumping ship and brawling.

On the Atlantic, a ship that left New Bedford for the Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean in 1865, an African American cook stabbed a sailor of European descent to death, saying the seafarer had called him a racial slur. The cook was transferred to a different boat and tried in the U.S. for murder. But the Atlantic’s trials weren’t through: Another ship rammed into it in the middle of the night, destroying its head rig, among other parts. It barely made it back from the depths of the Indian Ocean to a port in Mauritius after the collision. A decade later, after lengthy, costly repairs, a third of its crew wouldn’t make it back from sea at all after two of its smaller hunting boats went missing while searching for whales in a storm.

Whales figure prominently in the logbooks, too. In the margins, whalers depicted their captures with detailed illustrations; when they sighted an animal but didn’t catch it, whalers only drew its tail.

Their prey could have helped sequester the rising carbon emissions from the Industrial Revolution. Like trees, whales store carbon, and when they die, that carbon sinks along with their carcasses to the ocean floor.

The U.S. whaling industry, which faded by the 1920s, disrupted this natural cycle. But by merely documenting their experiences in unfamiliar waters, whalers have unwittingly allowed generations later to learn more about how the climate is changing.

“I find that quite awe-inspiring, to be able to say, ‘Wow, there was someone 250 years ago, describing something about the weather conditions, definitely not knowing what this could be used for down the track,’” Ummenhofer says. “I think that that’s pretty amazing.”

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.