Go Behind the Scenes at an Iconic Irish Library as Staff Move 700,000 Historical Treasures Into Storage

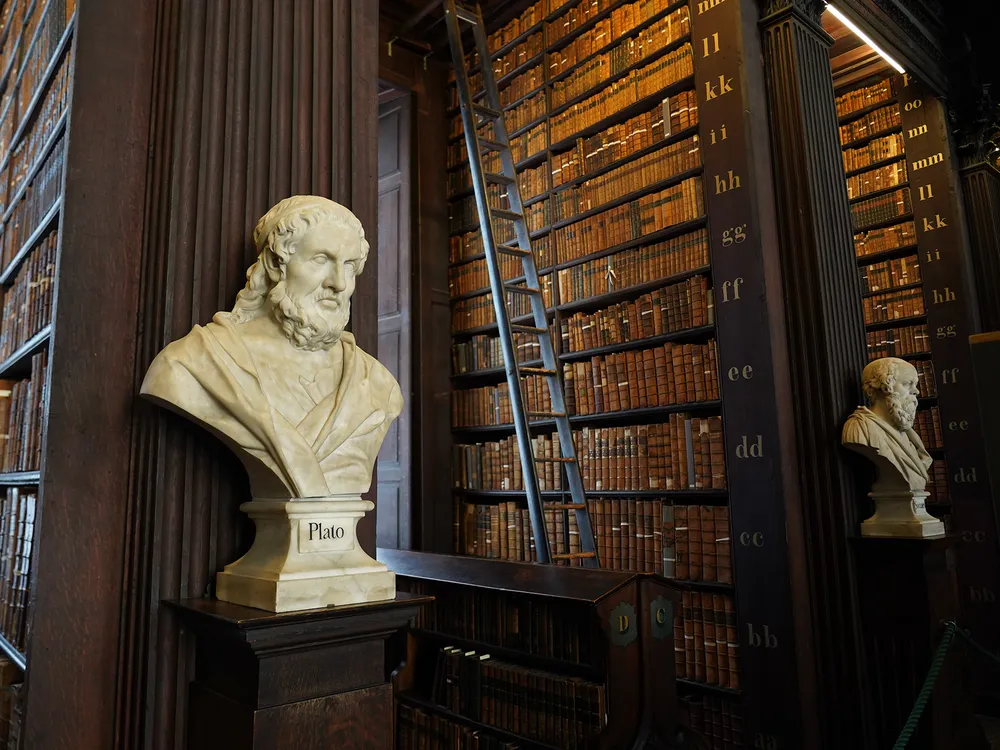

Go Behind the Scenes at an Iconic Irish Library as Staff Move 700,000 Historical Treasures Into Storage Trinity College Dublin’s Old Library will close for restoration and construction in 2027. What does that mean for the medieval manuscripts and books housed there? A bust of Plato in the Long Room at Trinity College Dublin Yvonne Gordon In the Old Library at Trinity College Dublin, a 433-year-old university in Ireland’s capital, rows of alcoves with dark oak bookcases line the central Long Room, whose Corinthian pillars stretch past the upper galleries to meet the carved timber ribs of the arched wooden ceiling. When I visited the library in late spring, the muted morning light from a tall window illuminated the books in one of the bays. A slender wooden ladder was suspended from a rail above the shelves, ready to reach the highest levels, where the spines of old leather books were lined up, their gold-tooled letters catching the light. Standing there, I felt as if this scene had remained undisturbed for hundreds of years. In reality, however, major changes are on the horizon for this beloved cultural institution—Ireland’s largest library. The Old Library is currently undergoing an ambitious redevelopment project that will combine medieval traditions with new technology and move hundreds of thousands of books at a cost of more than $100 million. In addition to protecting the early 18th-century building, the project will ensure the preservation of precious old texts and manuscripts, plus the valuable knowledge they contain, for future generations. View of the Long Room in Trinity's Old Library Ste Murray / Trinity College Dublin Trinity staff escalated their efforts to properly safeguard the library and its priceless collections in the aftermath of a 2019 fire that devastated Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral. The Old Library Redevelopment Project kicked off in 2022 and will begin its restoration and construction phase in 2027, with work estimated to be completed in 2030, according to the library’s chief manuscript conservator, John Gillis. The project will address pollution and dust accumulation on the books and introduce building improvements like air purification, environmental controls and fire protection. So, while the shelves in the Old Library are normally full (stacked side by side, the books would stretch more than 6.5 miles), on the day I visited, most of them stood empty. Nearly 200,000 books have been moved out thus far, leaving just eight bays where tomes have been left in place to give visitors—up to one million annually—an idea of what the shelves look like when full. The curved ribs of the Long Room’s ceiling almost form the inverse of the raised stitching on the spines of the old books. Gillis has worked in conservation at Trinity for more than 40 years. He believes that the vast majority of surviving manuscripts from early medieval Ireland (a period spanning roughly the fifth through ninth centuries) have passed through his hands. John Gillis, chief manuscript conservator at Trinity's library Yvonne Gordon “The collection includes many incunabula—that is, books printed before 1500,” Gillis says. While the library’s history stretches back to when Trinity College was established in Dublin in 1592, the collection boasts manuscripts and books much older than that. (The Old Library building itself was constructed between 1712 and 1732.) The library’s holdings include 30,000 books, pamphlets and maps acquired from a prominent Dutch family in 1802; the largest collection of children’s books in Ireland; and the first book printed in the Irish language, which dates to 1571. Other highlights range from Ireland’s only copy of William Shakespeare’s First Folio to national treasures like the Book of Kells, a stunning medieval manuscript. How the Old Library Redevelopment Project is transforming the Long Room Gillis’ work immerses him in the minutiae of lettering used in 400-year-old texts and the hairline cracks of vellum pages in early Irish manuscripts. But he has also been tasked with overseeing a huge project: the decanting, or temporary removal, of the Old Library’s entire collection of 700,000 objects, which will be moved into storage while the building is being refurbished. Old Library Redevelopment Project: Conserving the Old Library for future generations Despite the empty bookcases, visitors streaming through the Long Room can still admire artifacts like the Brian Boru harp, an instrument thought to date to the late Middle Ages that served as the model for the coat of arms of Ireland and the Guinness trademark. Temporary exhibitions are on view, too: for example, displays on Trinity alumni such as Nobel laureate Samuel Beckett, Gulliver’s Travels author Jonathan Swift and Dracula author Bram Stoker. Beyond the magnificent visual experience of standing in the Long Room, a visit here subtly hits the senses. The temperature is cooler than in adjacent rooms, and that familiar old book smell (caused by the chemical decomposition of paper and bookbindings) is readily apparent. The light is gentle; the acoustics are of hushed conversations and footfall. Will the space still feel—and smell—the same after the conservation project? “That’s a good question,” says Gillis. “Who knows?” Looking at the barren book bays, the conservator describes a remarkable phenomenon that occurred when the shelves were first emptied. “The whole building reacted to all of that weight being removed, as if stretching,” he recalls. “You had movement of floors, creaking, nails coming up out of floorboards.” Staff have observed changes to sound and light, too: Without the books acting as a buffer, the room is more echoey, with extra light pouring through the shelves. Bay B Timelapse - Old Library Decant Gillis says the temperature in the Long Room is always colder than outside. “This is a great old building for looking after itself,” he explains. “Although you get fluctuations in this building, nothing is ever too extreme.” The lack of worm infestations and mold growth show that the structure’s environmental conditions were in relatively good shape. But the building was leaky, and dust and dirt left behind by visitors, Dublin’s historic oil-burning lamps, and even vehicle exhaust took their toll. There’s less pollution nowadays, but it does still get in, especially when the library’s windows are opened in the summer. A new climate control system will address these issues. How conservators are safeguarding the Old Library’s collections It has taken a team of some 75 people around two years to remove the majority of the books from the Long Room’s shelves. This is the first time in nearly 300 years that they’ve been barren. “Nobody living has ever seen these shelves empty,” Gillis says. Wearing gloves, protective jackets and dust masks, staff carefully removed and cleaned each volume. They measured the books, added a radio-frequency identification (RFID) tag for cataloging and security purposes, and then either sent the texts on for conservation if damaged or to storage in a special climate-controlled, off-site facility if still in good condition. Gillis has worked in conservation for more than 40 years. Yvonne Gordon Removing all of the books from a single bay took up to one month each time. Exactly how daunting was this task, especially getting the books down from high shelves? According to Gillis, having the big, heavy books on the lower shelves helped. “You don’t want to be up a ladder trying to take off a big folio,” he says. The last eight bays will be emptied just before the library building closes in 2027, and all 200,000 books will be returned when the refurbishment is complete. Because the volumes are so old, every step of the delicate task has prioritized conservation. Each book has been gently vacuumed. “The suction level was reduced so it wasn’t too aggressive,” says Gillis. Even the dust—many of the books had not left the library for hundreds of years—was the subject of a scholarly study. The main findings were that the dust was made of organic material such as hair fibers and dead skin cells from visitors and staff. The books are stored off-site in special fireproof and waterproof archival boxes. Despite the fact that approximately 30,000 boxes are stacked in the warehouse, every tome remains available for research during the redevelopment project. That’s where the RFID tags and barcodes come in: When a book is requested, the library locates the relevant box and makes the text available to the researcher in a reading room. Conserving the Book of Kells and other medieval manuscripts The library’s most prized object, the Book of Kells, is currently housed below the Long Room in the Treasury, though it will be moved to the refurbished Printing House when conservation work begins in 2027. This manuscript, which contains the four Gospels of the Christian New Testament, dates to around 800, when it was likely illustrated by monks in an Irish monastery on the island of Iona in Scotland. The Book of Kells’ ornate decorations of Christian crosses and Celtic art have won it worldwide admiration. Need to know: Why is the Book of Kells so significant? According to Trinity College Dublin, the more than 1,200-year-old Book of Kells is distinct from other illuminated manuscripts “due to the sheer complexity and beauty of its ornamentation.” Featuring more adornments than other surviving manuscripts, the text has been described as the “work of angels.” The manuscript was gifted to Trinity College by Henry Jones, the bishop of Meath, in 1661. It’s displayed in a glass case in a darkened room whose light, humidity and temperature are carefully monitored to ensure the volume’s preservation. The specific pages on display are rotated every 8 to 12 weeks, and photography is not allowed. As well as overseeing the Book of Kells’ care, Gillis’ department looks after the storage and conservation of the library’s early printed books and special collections. While most of the Old Library’s contents have been moved to the off-site warehouse during the redevelopment, these “oldest and most valuable” holdings, as Trinity’s website describes them, are being kept on campus in a new storage space in the Ussher Library. Even in storage, the manuscripts need to be kept under specific conditions. Most were written on animal skins that are sensitive to humidity and temperature. All of the storage spaces are low-oxygen, which helps with preservation. Repairing and conserving damaged manuscripts is a big part of Gillis’ job. He also works to prevent damage to some of the collection’s earliest items. To date, Gillis has led the conservation of an 8th-century, pocket-size collection of gospels; a 7th-century Bible that is believed to be the earliest surviving Irish codex; and the 12th-century Book of Leinster, one of the earliest known Irish-language manuscripts. Illustrations from the Book of Kells Public domain via Wikimedia Commons When I visited the conservation lab earlier this year, Gillis was working on the Book of Leinster’s codicology—essentially, looking at the volume’s physical features to determine how it was put together and what it says about the era it was created in. The manuscript came to Trinity in the 18th century as a pile of gatherings in folders in a box, without a cover or binding. “Nobody has ever seen it as a single, complete volume,” Gillis says. “There remains the question: Was it bound ever?” Like the Book of Kells and most other early medieval Irish manuscripts, the Book of Leinster was written on vellum, or calf skin. To repair and stabilize the manuscript, Gillis is grafting new calf skins ordered from a specialist supplier onto the pages. Vellum can be challenging to work with, as aging and humidity cause tiny cracks and tears. While the lab is full of modern scientific equipment like conditioning chambers, humidifiers, fume hoods and freezers, sometimes traditional methods work best. To repair the Book of Leinster, conservators are using materials derived from casein, a protein found in milk, and isinglass, a collagen obtained from sturgeon fish, as an adhesive. Pages from the 12th-century Book of Leinster Yvonne Gordon “As we develop our conservation methods and approaches, they are typically based on the medieval practice, because they understood the quality of materials,” says Gillis. “It’s important that we remember the craft, that we are using skills, methods and materials that were developed in medieval times and are still relevant.” Trinity’s conservation work makes use of the latest scientific developments, too. A tool that is yielding new information about the manuscripts is DNA analysis, which can reveal the age, sex and species of animal that vellum and parchment are made from and, most importantly, where the skins came from. Medieval books transferred hands so often, it can be hard to trace their place of origin. While the DNA testing technique is still in early stages, Gillis says that it can “answer a lot of questions we have.” Already, the team has found that male calves weren’t the only members of their species whose skin was turned into vellum, as was previously thought. Female calves were slaughtered for this purpose, too. Digitization and the significance of the redevelopment project In addition to conserving the Old Library’s holdings, the ongoing project opens up new ways of experiencing them. After seeing the Book of Kells, visitors can enjoy an immersive digital experience that shows what’s in the library’s collections and tells the manuscript’s background story in an engaging way. Trinity staff are also digitizing many of the library’s collections, making them freely available online to audiences outside of academia. “This process of digitization enables us to democratize that access to anyone, anywhere globally who has an internet connection,” says Laura Shanahan, head of research collections at the Trinity library. Gillis hopes the project will inspire other preservation efforts in Ireland and overseas. For Trinity, the focus is on making the library’s collections broadly accessible while also protecting and caring for them so they survive long into the future. View of the immersive Book of Kells Experience Trinity College Dublin “The importance of preserving this material is to ensure that content is accessible for future generations of researchers who are looking back in time in 100, 200 or 300 years’ time to understand the evolution of our society, the cyclical nature of the issues that recur in history and the documentary heritage around everything from personal identity to how the world has evolved,” Shanahan says. Pádraig Ó Macháin, an expert on Irish manuscripts at University College Cork who is not involved in the conservation project, says: All libraries are sanctuaries for the written and the printed word, and hubs for the dissemination of knowledge. Libraries like Trinity’s, through their collections of incunabula and of medieval manuscripts, preserve unique records of the progress of learning through the centuries. They go to the very heart of civilization and articulate the curriculum vitae of the human race. Ó Macháin, who specializes in the study of Ireland’s handwritten heritage, adds, “Because libraries have a duty of care for future generations, it is vital that their capacity for preservation and transmission is periodically renewed or overhauled in a thorough and structured way, such as is taking place in Trinity at present.” A 2016 photo of shelves in the Long Room David Madison / Getty Images Get the latest History stories in your inbox.

Trinity College Dublin’s Old Library will close for restoration and construction in 2027. What does that mean for the medieval manuscripts and books housed there?

Go Behind the Scenes at an Iconic Irish Library as Staff Move 700,000 Historical Treasures Into Storage

Trinity College Dublin’s Old Library will close for restoration and construction in 2027. What does that mean for the medieval manuscripts and books housed there?

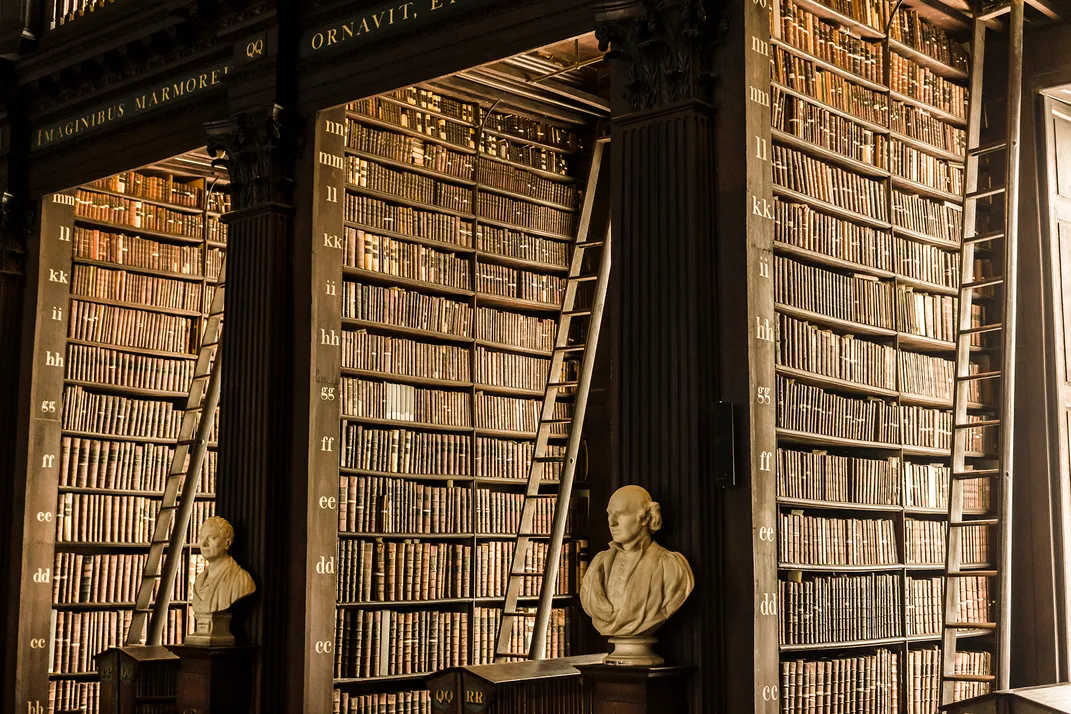

In the Old Library at Trinity College Dublin, a 433-year-old university in Ireland’s capital, rows of alcoves with dark oak bookcases line the central Long Room, whose Corinthian pillars stretch past the upper galleries to meet the carved timber ribs of the arched wooden ceiling.

When I visited the library in late spring, the muted morning light from a tall window illuminated the books in one of the bays. A slender wooden ladder was suspended from a rail above the shelves, ready to reach the highest levels, where the spines of old leather books were lined up, their gold-tooled letters catching the light. Standing there, I felt as if this scene had remained undisturbed for hundreds of years. In reality, however, major changes are on the horizon for this beloved cultural institution—Ireland’s largest library.

The Old Library is currently undergoing an ambitious redevelopment project that will combine medieval traditions with new technology and move hundreds of thousands of books at a cost of more than $100 million. In addition to protecting the early 18th-century building, the project will ensure the preservation of precious old texts and manuscripts, plus the valuable knowledge they contain, for future generations.

Trinity staff escalated their efforts to properly safeguard the library and its priceless collections in the aftermath of a 2019 fire that devastated Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral. The Old Library Redevelopment Project kicked off in 2022 and will begin its restoration and construction phase in 2027, with work estimated to be completed in 2030, according to the library’s chief manuscript conservator, John Gillis. The project will address pollution and dust accumulation on the books and introduce building improvements like air purification, environmental controls and fire protection.

So, while the shelves in the Old Library are normally full (stacked side by side, the books would stretch more than 6.5 miles), on the day I visited, most of them stood empty. Nearly 200,000 books have been moved out thus far, leaving just eight bays where tomes have been left in place to give visitors—up to one million annually—an idea of what the shelves look like when full. The curved ribs of the Long Room’s ceiling almost form the inverse of the raised stitching on the spines of the old books.

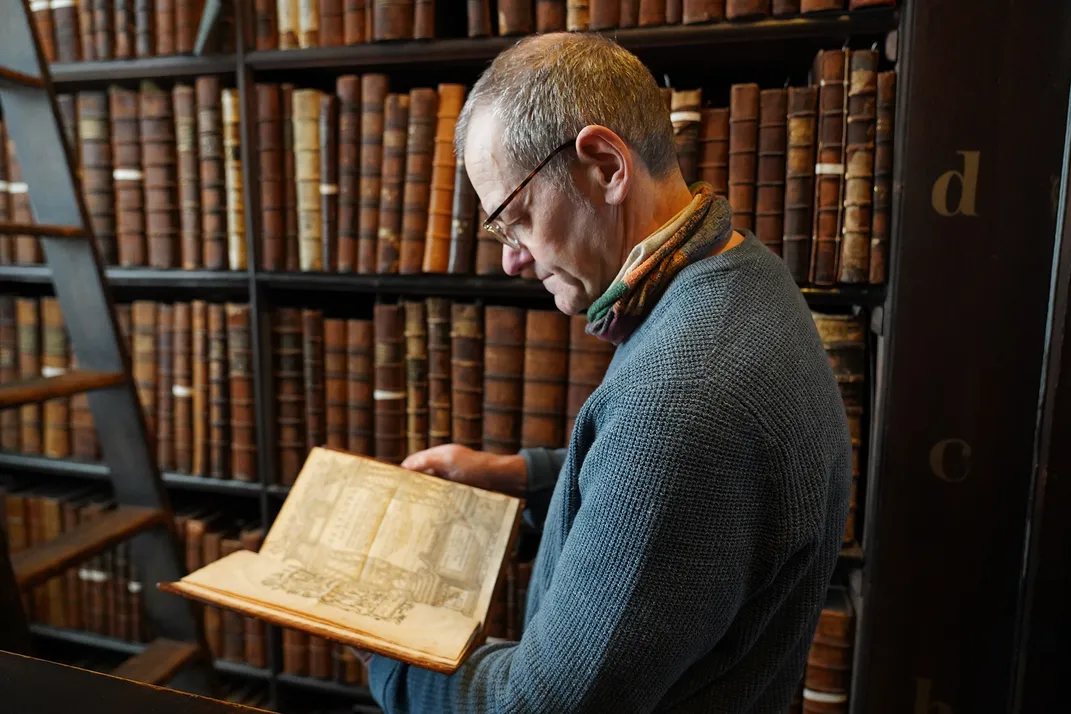

Gillis has worked in conservation at Trinity for more than 40 years. He believes that the vast majority of surviving manuscripts from early medieval Ireland (a period spanning roughly the fifth through ninth centuries) have passed through his hands.

“The collection includes many incunabula—that is, books printed before 1500,” Gillis says. While the library’s history stretches back to when Trinity College was established in Dublin in 1592, the collection boasts manuscripts and books much older than that. (The Old Library building itself was constructed between 1712 and 1732.)

The library’s holdings include 30,000 books, pamphlets and maps acquired from a prominent Dutch family in 1802; the largest collection of children’s books in Ireland; and the first book printed in the Irish language, which dates to 1571. Other highlights range from Ireland’s only copy of William Shakespeare’s First Folio to national treasures like the Book of Kells, a stunning medieval manuscript.

How the Old Library Redevelopment Project is transforming the Long Room

Gillis’ work immerses him in the minutiae of lettering used in 400-year-old texts and the hairline cracks of vellum pages in early Irish manuscripts. But he has also been tasked with overseeing a huge project: the decanting, or temporary removal, of the Old Library’s entire collection of 700,000 objects, which will be moved into storage while the building is being refurbished.

Old Library Redevelopment Project: Conserving the Old Library for future generations

Despite the empty bookcases, visitors streaming through the Long Room can still admire artifacts like the Brian Boru harp, an instrument thought to date to the late Middle Ages that served as the model for the coat of arms of Ireland and the Guinness trademark. Temporary exhibitions are on view, too: for example, displays on Trinity alumni such as Nobel laureate Samuel Beckett, Gulliver’s Travels author Jonathan Swift and Dracula author Bram Stoker.

Beyond the magnificent visual experience of standing in the Long Room, a visit here subtly hits the senses. The temperature is cooler than in adjacent rooms, and that familiar old book smell (caused by the chemical decomposition of paper and bookbindings) is readily apparent. The light is gentle; the acoustics are of hushed conversations and footfall.

Will the space still feel—and smell—the same after the conservation project? “That’s a good question,” says Gillis. “Who knows?” Looking at the barren book bays, the conservator describes a remarkable phenomenon that occurred when the shelves were first emptied. “The whole building reacted to all of that weight being removed, as if stretching,” he recalls. “You had movement of floors, creaking, nails coming up out of floorboards.” Staff have observed changes to sound and light, too: Without the books acting as a buffer, the room is more echoey, with extra light pouring through the shelves.

Bay B Timelapse - Old Library Decant

Gillis says the temperature in the Long Room is always colder than outside. “This is a great old building for looking after itself,” he explains. “Although you get fluctuations in this building, nothing is ever too extreme.” The lack of worm infestations and mold growth show that the structure’s environmental conditions were in relatively good shape.

But the building was leaky, and dust and dirt left behind by visitors, Dublin’s historic oil-burning lamps, and even vehicle exhaust took their toll. There’s less pollution nowadays, but it does still get in, especially when the library’s windows are opened in the summer. A new climate control system will address these issues.

How conservators are safeguarding the Old Library’s collections

It has taken a team of some 75 people around two years to remove the majority of the books from the Long Room’s shelves. This is the first time in nearly 300 years that they’ve been barren. “Nobody living has ever seen these shelves empty,” Gillis says.

Wearing gloves, protective jackets and dust masks, staff carefully removed and cleaned each volume. They measured the books, added a radio-frequency identification (RFID) tag for cataloging and security purposes, and then either sent the texts on for conservation if damaged or to storage in a special climate-controlled, off-site facility if still in good condition.

Removing all of the books from a single bay took up to one month each time. Exactly how daunting was this task, especially getting the books down from high shelves? According to Gillis, having the big, heavy books on the lower shelves helped. “You don’t want to be up a ladder trying to take off a big folio,” he says. The last eight bays will be emptied just before the library building closes in 2027, and all 200,000 books will be returned when the refurbishment is complete.

Because the volumes are so old, every step of the delicate task has prioritized conservation. Each book has been gently vacuumed. “The suction level was reduced so it wasn’t too aggressive,” says Gillis. Even the dust—many of the books had not left the library for hundreds of years—was the subject of a scholarly study. The main findings were that the dust was made of organic material such as hair fibers and dead skin cells from visitors and staff.

The books are stored off-site in special fireproof and waterproof archival boxes. Despite the fact that approximately 30,000 boxes are stacked in the warehouse, every tome remains available for research during the redevelopment project. That’s where the RFID tags and barcodes come in: When a book is requested, the library locates the relevant box and makes the text available to the researcher in a reading room.

Conserving the Book of Kells and other medieval manuscripts

The library’s most prized object, the Book of Kells, is currently housed below the Long Room in the Treasury, though it will be moved to the refurbished Printing House when conservation work begins in 2027. This manuscript, which contains the four Gospels of the Christian New Testament, dates to around 800, when it was likely illustrated by monks in an Irish monastery on the island of Iona in Scotland. The Book of Kells’ ornate decorations of Christian crosses and Celtic art have won it worldwide admiration.

Need to know: Why is the Book of Kells so significant?

- According to Trinity College Dublin, the more than 1,200-year-old Book of Kells is distinct from other illuminated manuscripts “due to the sheer complexity and beauty of its ornamentation.”

- Featuring more adornments than other surviving manuscripts, the text has been described as the “work of angels.”

The manuscript was gifted to Trinity College by Henry Jones, the bishop of Meath, in 1661. It’s displayed in a glass case in a darkened room whose light, humidity and temperature are carefully monitored to ensure the volume’s preservation. The specific pages on display are rotated every 8 to 12 weeks, and photography is not allowed.

As well as overseeing the Book of Kells’ care, Gillis’ department looks after the storage and conservation of the library’s early printed books and special collections. While most of the Old Library’s contents have been moved to the off-site warehouse during the redevelopment, these “oldest and most valuable” holdings, as Trinity’s website describes them, are being kept on campus in a new storage space in the Ussher Library.

Even in storage, the manuscripts need to be kept under specific conditions. Most were written on animal skins that are sensitive to humidity and temperature. All of the storage spaces are low-oxygen, which helps with preservation.

Repairing and conserving damaged manuscripts is a big part of Gillis’ job. He also works to prevent damage to some of the collection’s earliest items. To date, Gillis has led the conservation of an 8th-century, pocket-size collection of gospels; a 7th-century Bible that is believed to be the earliest surviving Irish codex; and the 12th-century Book of Leinster, one of the earliest known Irish-language manuscripts.

When I visited the conservation lab earlier this year, Gillis was working on the Book of Leinster’s codicology—essentially, looking at the volume’s physical features to determine how it was put together and what it says about the era it was created in. The manuscript came to Trinity in the 18th century as a pile of gatherings in folders in a box, without a cover or binding. “Nobody has ever seen it as a single, complete volume,” Gillis says. “There remains the question: Was it bound ever?”

Like the Book of Kells and most other early medieval Irish manuscripts, the Book of Leinster was written on vellum, or calf skin. To repair and stabilize the manuscript, Gillis is grafting new calf skins ordered from a specialist supplier onto the pages.

Vellum can be challenging to work with, as aging and humidity cause tiny cracks and tears. While the lab is full of modern scientific equipment like conditioning chambers, humidifiers, fume hoods and freezers, sometimes traditional methods work best. To repair the Book of Leinster, conservators are using materials derived from casein, a protein found in milk, and isinglass, a collagen obtained from sturgeon fish, as an adhesive.

“As we develop our conservation methods and approaches, they are typically based on the medieval practice, because they understood the quality of materials,” says Gillis. “It’s important that we remember the craft, that we are using skills, methods and materials that were developed in medieval times and are still relevant.”

Trinity’s conservation work makes use of the latest scientific developments, too. A tool that is yielding new information about the manuscripts is DNA analysis, which can reveal the age, sex and species of animal that vellum and parchment are made from and, most importantly, where the skins came from. Medieval books transferred hands so often, it can be hard to trace their place of origin. While the DNA testing technique is still in early stages, Gillis says that it can “answer a lot of questions we have.” Already, the team has found that male calves weren’t the only members of their species whose skin was turned into vellum, as was previously thought. Female calves were slaughtered for this purpose, too.

Digitization and the significance of the redevelopment project

In addition to conserving the Old Library’s holdings, the ongoing project opens up new ways of experiencing them. After seeing the Book of Kells, visitors can enjoy an immersive digital experience that shows what’s in the library’s collections and tells the manuscript’s background story in an engaging way. Trinity staff are also digitizing many of the library’s collections, making them freely available online to audiences outside of academia. “This process of digitization enables us to democratize that access to anyone, anywhere globally who has an internet connection,” says Laura Shanahan, head of research collections at the Trinity library.

Gillis hopes the project will inspire other preservation efforts in Ireland and overseas. For Trinity, the focus is on making the library’s collections broadly accessible while also protecting and caring for them so they survive long into the future.

“The importance of preserving this material is to ensure that content is accessible for future generations of researchers who are looking back in time in 100, 200 or 300 years’ time to understand the evolution of our society, the cyclical nature of the issues that recur in history and the documentary heritage around everything from personal identity to how the world has evolved,” Shanahan says.

Pádraig Ó Macháin, an expert on Irish manuscripts at University College Cork who is not involved in the conservation project, says:

All libraries are sanctuaries for the written and the printed word, and hubs for the dissemination of knowledge. Libraries like Trinity’s, through their collections of incunabula and of medieval manuscripts, preserve unique records of the progress of learning through the centuries. They go to the very heart of civilization and articulate the curriculum vitae of the human race.

Ó Macháin, who specializes in the study of Ireland’s handwritten heritage, adds, “Because libraries have a duty of care for future generations, it is vital that their capacity for preservation and transmission is periodically renewed or overhauled in a thorough and structured way, such as is taking place in Trinity at present.”