A New Bee Crisis Could Make Your Food Scarce and Expensive

Sammy Ramsey was having a hard time getting information. It was 2019, and he was in Thailand, researching parasites that kill bees. But Ramsey was struggling to get one particular Thai beekeeper to talk to him. In nearby bee yards, Ramsey had seen hives overrun with pale, ticklike creatures, each one smaller than a sharpened pencil point, scuttling at ludicrous speed. For each parasite on the hive surface, there were exponentially more hidden from view inside, feasting on developing bees. But this quiet beekeeper’s colonies were healthy. Ramsey, an entomologist, wanted to know why.The tiny parasites were a honeybee pest from Asia called tropilaelaps mites—tropi mites for short. In 2024 their presence was confirmed in Europe for the first time, and scientists are certain the mites will soon appear in the Americas. They can cause an epic collapse of honeybee populations that could devastate farms across the continent. Honeybees are essential agricultural workers. Trucked by their keepers from field to field, they help farmers grow more than 130 crops—from nuts to fruits to vegetables to alfalfa hay for cattle—worth more than $15 billion annually. If tropi mites kill those bees, the damage to the farm economy would be staggering.Other countries have already felt the effects of the mite. The parasites blazed a murderous path through Southeast Asia and India in the 1960s and 1970s. Because crops are smaller and more diverse there than in giant American farms, the economic effects of the mite were felt mainly by beekeepers, who experienced massive colony losses soon after tropilaelaps arrived. The parasite spread through northern Asia, the Middle East, Oceania and Central Asia. And now Europe. That sighting sounded alarms on this side of the Atlantic because the ocean won’t serve as a barrier for long. Mites can stow away on ships, on smuggled or imported bees. “The acceleration of the tropi mite’s spread has become so clear that no one can deny it’s gunning for us,” said Ramsey, now an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, on the Beekeeping Today podcast in 2023.On supporting science journalismIf you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.Ramsey, who is small and energetic like the creatures he studies, had traveled to Thailand in 2019 to gather information on techniques that the country’s beekeepers, who had lived with the mite for decades, were using to keep their bees alive. But the silent keeper he was interviewing was reluctant to share. Maybe the man feared this nosy foreigner would give away his beekeeping secrets—Ramsey didn’t know.But then the keeper’s son tapped his father on the shoulder. “I think that’s Black Thai,” he said, pointing at Ramsey. On his phone, the young man pulled up a video that showed Ramsey’s YouTube alter ego, “Black Thai,” singing a Thai pop song with a gospel lilt. Ramsey, who is Black—and “a scientist, a Christian, queer, a singer,” he says—had taught himself the language by binging Thai movies and music videos. Now that unusual hobby was coming in handy.Without bees the almond yield drops drastically. Other foods, such as apples, cherries, blueberries, and some pit fruits and vine fruits, are similarly dependent on bee pollination.The reticent keeper started to speak. “His face lit up,” Ramsey recalls. “He got really talkative.” The keeper described, in detail, the technique he was using to keep mite populations down. It involved an industrial version of a caustic acid naturally produced by ants. Ramsey thinks the substance might be a worldwide key to fighting the mite, a menace that is both tiny and colossal at the same time.Ramsey first saw a tropilaelaps mite in 2017, also in Thailand. He had traveled there to study another damaging parasite of honeybees, the aptly named Varroa destructor mites. But when he opened his first hive, he instead saw the stunning effect of tropilaelaps. Stunted bees were crawling across the hive frames, and the next-generation brood of cocooned pupae were staring out of their hexagonal cells in the hive with purple-pigmented eyes, exposed to the elements after their infested cell caps had been chewed away by nurse bees in a frenzy to defend the colony. At the hive entrances, bees were trembling on the ground or wandering in drunken circles. Their wings and legs were deformed, abdomens misshapen, and their bodies had a greasy sheen where hairs had worn off. The colony was doomed. “I was told there was no saving that one,” Ramsey says. He had never seen anything like it.When he got home, he started reading up on the mites. There was not much to read. Somewhere in Southeast Asia in the middle of the last century, two of four known species of tropilaelaps (Tropilaelaps mercedesae and T. clareae) had jumped to European honeybees from Apis dorsata, the giant honeybee with which it evolved in Asia. Parasites will not, in their natural settings, kill their hosts, “for the same reason you don’t want to burn your house down,” Ramsey said at a beekeeping conference in 2023. “You live there.”A tiny tropi mite (on bee at left) crawls on a bee.The giant honeybees in Asia, a species not used in commercial beekeeping, long ago had reached a mutual accommodation with the mites. But the European bees that Asian beekeepers raised to make honey were entirely naïve to the parasites. When the mites encountered one of those colonies, they almost always killed it. Because beekeepers cluster their beehives in apiaries, moving them en masse from one bee yard to the next, the mite could survive the loss of its host colony by jumping to a new one. “It would normally destroy itself,” Ramsey said at the conference, “if not for us.”Kept alive by human beekeepers, the mite moved through Asia, across the Middle East and, most recently, to the Ukraine-Russia border and to the country of Georgia. “It is westward expanding, it is eastward expanding, it is northward expanding,” says University of Alberta honeybee biologist Olav Rueppell. This move into Europe is ominous, Ramsey and Rueppell say. Canada has, in the past, imported queen bees from Ukraine. If the mite arrived in Canada on a Ukrainian bee, it could be a matter of only weeks or months before it crossed the northern U.S. border.Today between a quarter and half of U.S. bees die every year, forcing keepers to continually buy replacement “packages” of bees and queens to rebuild.The almond industry would be especially hard-hit by the mite. Two thirds of the national herd of commercial bees—about two million colonies—are trucked to California’s Central Valley every February to pollinate nearly 1.5 million acres of almond trees. Without bees the almond yield drops drastically. Other foods, such as apples, cherries, blueberries, and some pit fruits and vine fruits, are similarly dependent on bee pollination. We wouldn’t starve without them: corn, wheat and rice, for instance, are pollinated by wind. But fruits and nuts, as well as vegetables such as broccoli, carrots, celery, cucumbers and herbs, would become more scarce and more expensive. Because the cattle industry depends on alfalfa and clover for feed, beef and dairy products would also cost a lot more.Damage from tropilaelaps, many experts say, could vastly exceed the harm seen from its predecessor pest, the V. destructor mite. The varroa scourge arrived in the U.S. in 1987, when a Wisconsin beekeeper noticed a reddish-brown, ticklike creature riding on the back of one of his bees. Like tropilaelaps, varroa mites originated in Asia and then swept across the world. At first beekeepers were able to keep managed colonies alive with the help of easy-to-apply synthetic pesticides. But by 2005 the mites developed resistance to those chemicals, and beekeepers suffered the first wave of what has become a tsunami of losses. Today between a quarter and half of U.S. bees die every year, forcing keepers to continually buy replacement “packages” of bees and queens to rebuild. This past winter keepers saw average losses ranging upward of 70 percent. Scientists believe varroa mites are culprits in most of those losses, making bees susceptible to a variety of environmental insults, from mite-vectored viruses to fungal infections to pesticides. “In the old days we were shouting and swearing if we had an 8 percent dud rate; now people would be happy with that,” says beekeeper John Miller. He serves on the board of Project Apis m. (PAm), a bee-research organization that is a joint venture of the beekeeping and almond industries and was one of Ramsey’s early funders.When Ramsey joined the University of Maryland’s bee laboratory as a grad student in 2014, he began working on varroa. He discovered that the mites fed not on the bloodlike hemolymph of adult bees, as generations of scientists before him had assumed, but on “fat bodies,” organs similar to the liver. “For the past 70 years research done around varroa mites was based on the wrong information,” Ramsey says. (Recently published research indicates that the mites also feed on hemolymph while reproducing in a developing brood.)Ramsey’s finding helped to explain how varroa mites make the effects of all the other insults to honeybee health—pesticides, pathogens, poor nutrition—so much worse. Honeybees’ detoxification and immune systems reside in the fat bodies, which also store the nutrients responsible for growth and for protein and fat synthesis. Bees’ livers protect them from pesticides, Ramsey says. But when varroa mites attack honeybee livers, the pollinators succumb to pesticide exposures that would not ordinarily kill them.Entomologist Sammy Ramsey says such mites can destroy the American bee population.Now Ramsey is going after tropilaelaps as well as varroa mites. He continues his research into countermeasures and teaches both entomology and science communication classes in Boulder. In the years since he first sang as Black Thai, he has also become “Dr. Sammy,” a popular science communicator who is using his growing social media platform to sound the alarm about the parasites.In April 2024 I was watching him lead a graduate seminar when his watch chimed. “There’s a freezer alert in my lab,” he said. The temperature appeared to be off. We climbed the stairs to his lab overlooking the university’s soccer fields and examined the freezer, which didn’t seem to be in any immediate danger. Inside, stacked in boxes, lay an extensive archive of honeybees and mites that prey on them. Ramsey pulled out a tube of tropi mites.It was easy to see the enormity—or rather the minusculity—of the problem. The mites are about half a millimeter wide, one-third the size of varroa—“on the margins of what we are capable of seeing with the unassisted eye,” Ramsey says. Seen on video, they crawl so quickly that it looks as if the film speed has been doubled or tripled. Unlike varroa mites, which are brownish-red and relatively easy to spot, to the naked eye tropi mites are “almost devoid of color,” says Natasha Garcia-Andersen, a biologist for the city of Washington, D.C., who traveled to Thailand in January 2024 with a group of North American apiary inspectors to learn about the mites. “You see it, and you can’t tell—Is that a mite or dirt or debris?”Auburn University entomologist Geoff Williams led that Thailand mission. “There’s a decent chance that inspectors might be the first ones to identify a tropi mite in North America,” Williams says. The Thailand journey allowed them to see firsthand what they might soon be contending with. “It was eye-opening, watching these bee inspectors saying, ‘Holy crap, look at these tiny mites. How are you supposed to see that?’”Daniel P. Huffman; Source: Mallory Jordan and Stephanie Rogers, Auburn University. November 5, 2024, map hosted by Apiary Inspectors of America (reference); Data curated by: Rogan Tokach, Dan Aurell, Geoff Williams/Auburn University; Samantha Brunner/North Dakota Department of Agriculture; Natasha Garcia-Andersen/District of Columbia Department of Energy and the EnvironmentRather than looking for the mites, Thai beekeepers diagnose tropilaelaps infestations by examining the state of their bees, says Samantha Muirhead, provincial apiculturist for the government of Alberta, Canada, and another of the inspectors on the Thailand expedition. “You see the damage,” she says—uncapped brood cells, chewed-up pupae, ailing adults. An unaccustomed North American beekeeper, however, would probably attribute the destruction to varroa mites. “You have to change the way you’re looking,” she says.Williams and his team at Auburn are also investigating alternative ways of detection. They are working to develop environmental DNA tests to identify the presence of tropilaelaps DNA in hives. Inspectors would swab the frames or bottom boards of “sentinel hives”—surveillance colonies—to detect an invasion. But any systematic monitoring for tropi mites using this kind of DNA is still years away.For now scientists are struggling to formulate a plan of action against a menace they don’t fully understand. “We have this huge void of knowledge,” says California beekeeper and researcher Randy Oliver. Scientists don’t know how the mites spread between colonies. Where do they go when colonies swarm? No one has any idea. Can they infect other vulnerable bee species? Do they feed on fat bodies, hemolymph, some combination of the two, or something else entirely? Studies show that tropi mites carry at least two of the same viruses as varroa mites. How many more might they carry? “Part of the rush to action now is the paucity of information,” Rueppell says.Existing varroa research does provide some knowledge by analogy, but there are several differences between the two mites. Varroa mite populations double in a month, for instance, but tropilaelaps populations do so in a matter of days. Varroa mites tend to bite their bee victims only once; tropi mites feed from multiple entry wounds, creating disabling scar tissue. And for many years scientists thought tropi mites couldn’t survive in colder climates like that of the northern U.S., because the parasites appeared to have a significant evolutionary disadvantage compared with varroa: Tropi mites can feed only on developing bees because their small mouths can’t penetrate adult bee exoskeletons. Queens stop laying eggs in cold weather, so in theory tropi mites shouldn’t have enough food to last the winter. But about a decade ago the mites were found in colder regions of Korea—and then in northern China and Georgia. “We thought they wouldn’t survive in colonies that overwinter,” says Jeff Pettis, a former U.S. Department of Agriculture research scientist who now heads Apimondia, an international beekeeping federation. “We know they get through the winter now,” he says. Scientists just don’t know how.“It’s worse than varroa, and I don’t think we’ll ever be prepared fully.” —John Miller, beekeeperOne theory is that the mites disperse onto mice or rats that move into beehives during the cold months—the 1961 paper that first described tropilaelaps noted there were mites on rats in the Philippines. Scientists are exploring other overwintering theories as well. Perhaps the mites feed for brief, broodless periods on other pests in the hive, such as hive beetles and wax moths.Another possibility, highlighted by Williams’s recent research, is that more bee larvae may persist in colder climates than previously thought, perhaps enough to feed the mites. His team has found small amounts of brood snug in wax-covered cells in hives as far north as New York State and Oregon in the winter. “My gut feeling is that these colonies might have a little bit of brood through the winter,” Williams says.In 2022 Ramsey returned to Thailand and set up several research apiaries for what he calls his “Fight the Mite” initiative, testing different treatments to kill tropi mites. It isn’t easy. Whereas varroa mites live on adult bees for much of their life cycle, tropi mites live mostly inside brood cells, safe from most pesticides, which can’t penetrate the wax-capped hexagons.A close-up view of a tropi mite.But Ramsey learned from the Thai beekeepers he met on his 2019 visit that many of them had been using formic acid, the compound produced by ants that can get into capped cells. The beekeepers had been dipping paint stirrers in industrial-grade cans of the stuff and sticking the blades under hive entrances. Fumes then seeped through the wax caps and killed the mites. Ramsey experimented with various formulations and applications in 2022 and found that this method worked, although the chemical is highly volatile, caustic and difficult to apply. It’s hard on both bees and beekeepers. “Heat treatments”—heating hives to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit for two-plus hours—also took a dent out of mite populations in Ramsey’s tests.Williams, meanwhile, has been studying “cultural techniques” for controlling the mites, such as strategic breaks in brood cycles. Beekeepers in Thailand typically keep fewer bees in relatively small colonies, much tinier than the thousands or tens of thousands that some North American commercial outfits maintain. And when mite loads get bad, some Thai beekeepers also will discard their brood completely and start over. “They’re not afraid to quite literally throw away brood frames when they have mites,” Williams says.These strategies are difficult to apply at the scale of North American industrial apiculture. But large commercial outfits, which can keep anywhere from dozens to tens of thousands of colonies, may be able to adopt other tactics such as “indoor shedding”—storing all their hives in refrigerated sheds for a number of weeks to force an extended brood break. It’s likely that an effective approach will employ not one silver bullet but rather some combination of strategies—chemicals, heat, brood breaks—to avoid developing resistance. “You want to be able to rotate treatments to pound away at the mite,” Oliver says.Honeybees crawl over a comb of hexagonal hive cells, some filled with honey and pollen.These different techniques highlight the need for both varied approaches and, Ramsey believes, a varied group of scientists attacking the problem. “To study insects is to study diversity,” Ramsey says. “It is not a glitch in biology that the most successful group of animals on this planet is the most diverse group of animals. One of the key features of diversity is the capacity to solve problems in different ways.” To stave off the tropi mite, scientists will need to attack the problem from every angle they can conceive.On an afternoon in late May 2024, Ramsey, clad in a protective suit, opened a test hive in a holding yard on the east side of Boulder. The last cold day of spring was behind us, and everything had come into bloom at once—a riot of flowering locust, linden, lilac; glowing hay fields; distant, rock-spiked mountains curving northward out of sight. Massive bumblebees flew from flower to flower on a black locust tree above us, hovering like dark blimps in the sky.These were supposed to be Ramsey’s “pampered” bees, a control group to compare with more infested hives. They had, of course, been spared the ravages of tropi mites, which were still an ocean away. But they had been given frequent treatments for varroa mites. On the first frame Ramsey pulled, however, he saw sick bees everywhere. “This young lady clearly has a virus,” he said, noting a female’s “greasy,” prematurely bald abdomen. He pointed to a sinister dot the color of dried blood between another bee’s wings: a varroa mite. The bees were cranky, swooping and dive-bombing, and there weren’t enough brood cells on the frame. Ramsey sang to the bees in his gospel-tinged tenor, puffing at the hive with his smoker. “It seems like some of our best treatments for varroa mite are failing,” he said, examining another frame.The American practice of beekeeping is built on abundance—stacks of bee boxes, fields of flowers, vats of honey, teeming hives and expanses of wax-capped brood. But in Thailand, where tropilaelaps has been established for decades, beekeeping often is an exercise in scarcity—small colonies, meager honey production, uncapped pupae. Beekeepers there think far less about varroa mites than they worry about tropilaelaps, which outcompeted varroa years ago.There are so many threats facing modern honeybees—a daunting diversity, and we are ready for none of them. In 2023 the Georgia Department of Agriculture confirmed the presence of the yellow-legged hornet—Vespa velutina—in the U.S. Like the northern giant “murder” hornet found in Washington State in 2019 and declared eradicated in the U.S. last year, the yellow-legged insect is a “terrible beast,” says PAm executive director Danielle Downey. It hovers in front of beehives—a behavior called hawking—and rips the heads, abdomens and wings from returning foragers like a hunter field-dressing game. Then the hornet takes the thorax back to its nest. When the hornet first arrived in Europe, beekeepers lost 50 to 80 percent of their colonies. “The thing eats everything. One nest can eat 25 pounds of insects,” Downey says. “We’ve identified a lot of problems. How many crises can we handle?”In the spring of 2024, when the research paper confirming tropi mites were in Europe was published, Canada suspended all imports of Ukrainian hives and queens. For now that means this route for the mite’s arrival in North America is off the table. But trade—legal or surreptitious—could start again, and with the mites’ ferocious reproduction rates, it takes only one female to infect an entire continent. So this reprieve is probably only temporary. “We know the pathway and the threat it poses,” Downey says.A beekeeper with an infestation could spread the mite across the continent within a year; beehive die-offs would probably begin several months later. “It’s worse than varroa, and I don’t think we’ll ever be prepared fully,” Miller says.But Ramsey and his colleagues are racing to make sure they know every option available to them—formic acid, heat treatments, rotation, brood breaks—so that when the tropilaelaps mite does, at last, inevitably arrive, they will be ready. Researchers and beekeepers, Ramsey says, are trying to murder these parasites.

Scientists are racing to stop a tiny mite that could devastate the pollinators and agriculture

Sammy Ramsey was having a hard time getting information. It was 2019, and he was in Thailand, researching parasites that kill bees. But Ramsey was struggling to get one particular Thai beekeeper to talk to him. In nearby bee yards, Ramsey had seen hives overrun with pale, ticklike creatures, each one smaller than a sharpened pencil point, scuttling at ludicrous speed. For each parasite on the hive surface, there were exponentially more hidden from view inside, feasting on developing bees. But this quiet beekeeper’s colonies were healthy. Ramsey, an entomologist, wanted to know why.

The tiny parasites were a honeybee pest from Asia called tropilaelaps mites—tropi mites for short. In 2024 their presence was confirmed in Europe for the first time, and scientists are certain the mites will soon appear in the Americas. They can cause an epic collapse of honeybee populations that could devastate farms across the continent. Honeybees are essential agricultural workers. Trucked by their keepers from field to field, they help farmers grow more than 130 crops—from nuts to fruits to vegetables to alfalfa hay for cattle—worth more than $15 billion annually. If tropi mites kill those bees, the damage to the farm economy would be staggering.

Other countries have already felt the effects of the mite. The parasites blazed a murderous path through Southeast Asia and India in the 1960s and 1970s. Because crops are smaller and more diverse there than in giant American farms, the economic effects of the mite were felt mainly by beekeepers, who experienced massive colony losses soon after tropilaelaps arrived. The parasite spread through northern Asia, the Middle East, Oceania and Central Asia. And now Europe. That sighting sounded alarms on this side of the Atlantic because the ocean won’t serve as a barrier for long. Mites can stow away on ships, on smuggled or imported bees. “The acceleration of the tropi mite’s spread has become so clear that no one can deny it’s gunning for us,” said Ramsey, now an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, on the Beekeeping Today podcast in 2023.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ramsey, who is small and energetic like the creatures he studies, had traveled to Thailand in 2019 to gather information on techniques that the country’s beekeepers, who had lived with the mite for decades, were using to keep their bees alive. But the silent keeper he was interviewing was reluctant to share. Maybe the man feared this nosy foreigner would give away his beekeeping secrets—Ramsey didn’t know.

But then the keeper’s son tapped his father on the shoulder. “I think that’s Black Thai,” he said, pointing at Ramsey. On his phone, the young man pulled up a video that showed Ramsey’s YouTube alter ego, “Black Thai,” singing a Thai pop song with a gospel lilt. Ramsey, who is Black—and “a scientist, a Christian, queer, a singer,” he says—had taught himself the language by binging Thai movies and music videos. Now that unusual hobby was coming in handy.

Without bees the almond yield drops drastically. Other foods, such as apples, cherries, blueberries, and some pit fruits and vine fruits, are similarly dependent on bee pollination.

The reticent keeper started to speak. “His face lit up,” Ramsey recalls. “He got really talkative.” The keeper described, in detail, the technique he was using to keep mite populations down. It involved an industrial version of a caustic acid naturally produced by ants. Ramsey thinks the substance might be a worldwide key to fighting the mite, a menace that is both tiny and colossal at the same time.

Ramsey first saw a tropilaelaps mite in 2017, also in Thailand. He had traveled there to study another damaging parasite of honeybees, the aptly named Varroa destructor mites. But when he opened his first hive, he instead saw the stunning effect of tropilaelaps. Stunted bees were crawling across the hive frames, and the next-generation brood of cocooned pupae were staring out of their hexagonal cells in the hive with purple-pigmented eyes, exposed to the elements after their infested cell caps had been chewed away by nurse bees in a frenzy to defend the colony. At the hive entrances, bees were trembling on the ground or wandering in drunken circles. Their wings and legs were deformed, abdomens misshapen, and their bodies had a greasy sheen where hairs had worn off. The colony was doomed. “I was told there was no saving that one,” Ramsey says. He had never seen anything like it.

When he got home, he started reading up on the mites. There was not much to read. Somewhere in Southeast Asia in the middle of the last century, two of four known species of tropilaelaps (Tropilaelaps mercedesae and T. clareae) had jumped to European honeybees from Apis dorsata, the giant honeybee with which it evolved in Asia. Parasites will not, in their natural settings, kill their hosts, “for the same reason you don’t want to burn your house down,” Ramsey said at a beekeeping conference in 2023. “You live there.”

A tiny tropi mite (on bee at left) crawls on a bee.

The giant honeybees in Asia, a species not used in commercial beekeeping, long ago had reached a mutual accommodation with the mites. But the European bees that Asian beekeepers raised to make honey were entirely naïve to the parasites. When the mites encountered one of those colonies, they almost always killed it. Because beekeepers cluster their beehives in apiaries, moving them en masse from one bee yard to the next, the mite could survive the loss of its host colony by jumping to a new one. “It would normally destroy itself,” Ramsey said at the conference, “if not for us.”

Kept alive by human beekeepers, the mite moved through Asia, across the Middle East and, most recently, to the Ukraine-Russia border and to the country of Georgia. “It is westward expanding, it is eastward expanding, it is northward expanding,” says University of Alberta honeybee biologist Olav Rueppell. This move into Europe is ominous, Ramsey and Rueppell say. Canada has, in the past, imported queen bees from Ukraine. If the mite arrived in Canada on a Ukrainian bee, it could be a matter of only weeks or months before it crossed the northern U.S. border.

Today between a quarter and half of U.S. bees die every year, forcing keepers to continually buy replacement “packages” of bees and queens to rebuild.

The almond industry would be especially hard-hit by the mite. Two thirds of the national herd of commercial bees—about two million colonies—are trucked to California’s Central Valley every February to pollinate nearly 1.5 million acres of almond trees. Without bees the almond yield drops drastically. Other foods, such as apples, cherries, blueberries, and some pit fruits and vine fruits, are similarly dependent on bee pollination. We wouldn’t starve without them: corn, wheat and rice, for instance, are pollinated by wind. But fruits and nuts, as well as vegetables such as broccoli, carrots, celery, cucumbers and herbs, would become more scarce and more expensive. Because the cattle industry depends on alfalfa and clover for feed, beef and dairy products would also cost a lot more.

Damage from tropilaelaps, many experts say, could vastly exceed the harm seen from its predecessor pest, the V. destructor mite. The varroa scourge arrived in the U.S. in 1987, when a Wisconsin beekeeper noticed a reddish-brown, ticklike creature riding on the back of one of his bees. Like tropilaelaps, varroa mites originated in Asia and then swept across the world. At first beekeepers were able to keep managed colonies alive with the help of easy-to-apply synthetic pesticides. But by 2005 the mites developed resistance to those chemicals, and beekeepers suffered the first wave of what has become a tsunami of losses. Today between a quarter and half of U.S. bees die every year, forcing keepers to continually buy replacement “packages” of bees and queens to rebuild. This past winter keepers saw average losses ranging upward of 70 percent. Scientists believe varroa mites are culprits in most of those losses, making bees susceptible to a variety of environmental insults, from mite-vectored viruses to fungal infections to pesticides. “In the old days we were shouting and swearing if we had an 8 percent dud rate; now people would be happy with that,” says beekeeper John Miller. He serves on the board of Project Apis m. (PAm), a bee-research organization that is a joint venture of the beekeeping and almond industries and was one of Ramsey’s early funders.

When Ramsey joined the University of Maryland’s bee laboratory as a grad student in 2014, he began working on varroa. He discovered that the mites fed not on the bloodlike hemolymph of adult bees, as generations of scientists before him had assumed, but on “fat bodies,” organs similar to the liver. “For the past 70 years research done around varroa mites was based on the wrong information,” Ramsey says. (Recently published research indicates that the mites also feed on hemolymph while reproducing in a developing brood.)

Ramsey’s finding helped to explain how varroa mites make the effects of all the other insults to honeybee health—pesticides, pathogens, poor nutrition—so much worse. Honeybees’ detoxification and immune systems reside in the fat bodies, which also store the nutrients responsible for growth and for protein and fat synthesis. Bees’ livers protect them from pesticides, Ramsey says. But when varroa mites attack honeybee livers, the pollinators succumb to pesticide exposures that would not ordinarily kill them.

Entomologist Sammy Ramsey says such mites can destroy the American bee population.

Now Ramsey is going after tropilaelaps as well as varroa mites. He continues his research into countermeasures and teaches both entomology and science communication classes in Boulder. In the years since he first sang as Black Thai, he has also become “Dr. Sammy,” a popular science communicator who is using his growing social media platform to sound the alarm about the parasites.

In April 2024 I was watching him lead a graduate seminar when his watch chimed. “There’s a freezer alert in my lab,” he said. The temperature appeared to be off. We climbed the stairs to his lab overlooking the university’s soccer fields and examined the freezer, which didn’t seem to be in any immediate danger. Inside, stacked in boxes, lay an extensive archive of honeybees and mites that prey on them. Ramsey pulled out a tube of tropi mites.

It was easy to see the enormity—or rather the minusculity—of the problem. The mites are about half a millimeter wide, one-third the size of varroa—“on the margins of what we are capable of seeing with the unassisted eye,” Ramsey says. Seen on video, they crawl so quickly that it looks as if the film speed has been doubled or tripled. Unlike varroa mites, which are brownish-red and relatively easy to spot, to the naked eye tropi mites are “almost devoid of color,” says Natasha Garcia-Andersen, a biologist for the city of Washington, D.C., who traveled to Thailand in January 2024 with a group of North American apiary inspectors to learn about the mites. “You see it, and you can’t tell—Is that a mite or dirt or debris?”

Auburn University entomologist Geoff Williams led that Thailand mission. “There’s a decent chance that inspectors might be the first ones to identify a tropi mite in North America,” Williams says. The Thailand journey allowed them to see firsthand what they might soon be contending with. “It was eye-opening, watching these bee inspectors saying, ‘Holy crap, look at these tiny mites. How are you supposed to see that?’”

Daniel P. Huffman; Source: Mallory Jordan and Stephanie Rogers, Auburn University. November 5, 2024, map hosted by Apiary Inspectors of America (reference); Data curated by: Rogan Tokach, Dan Aurell, Geoff Williams/Auburn University; Samantha Brunner/North Dakota Department of Agriculture; Natasha Garcia-Andersen/District of Columbia Department of Energy and the Environment

Rather than looking for the mites, Thai beekeepers diagnose tropilaelaps infestations by examining the state of their bees, says Samantha Muirhead, provincial apiculturist for the government of Alberta, Canada, and another of the inspectors on the Thailand expedition. “You see the damage,” she says—uncapped brood cells, chewed-up pupae, ailing adults. An unaccustomed North American beekeeper, however, would probably attribute the destruction to varroa mites. “You have to change the way you’re looking,” she says.

Williams and his team at Auburn are also investigating alternative ways of detection. They are working to develop environmental DNA tests to identify the presence of tropilaelaps DNA in hives. Inspectors would swab the frames or bottom boards of “sentinel hives”—surveillance colonies—to detect an invasion. But any systematic monitoring for tropi mites using this kind of DNA is still years away.

For now scientists are struggling to formulate a plan of action against a menace they don’t fully understand. “We have this huge void of knowledge,” says California beekeeper and researcher Randy Oliver. Scientists don’t know how the mites spread between colonies. Where do they go when colonies swarm? No one has any idea. Can they infect other vulnerable bee species? Do they feed on fat bodies, hemolymph, some combination of the two, or something else entirely? Studies show that tropi mites carry at least two of the same viruses as varroa mites. How many more might they carry? “Part of the rush to action now is the paucity of information,” Rueppell says.

Existing varroa research does provide some knowledge by analogy, but there are several differences between the two mites. Varroa mite populations double in a month, for instance, but tropilaelaps populations do so in a matter of days. Varroa mites tend to bite their bee victims only once; tropi mites feed from multiple entry wounds, creating disabling scar tissue. And for many years scientists thought tropi mites couldn’t survive in colder climates like that of the northern U.S., because the parasites appeared to have a significant evolutionary disadvantage compared with varroa: Tropi mites can feed only on developing bees because their small mouths can’t penetrate adult bee exoskeletons. Queens stop laying eggs in cold weather, so in theory tropi mites shouldn’t have enough food to last the winter. But about a decade ago the mites were found in colder regions of Korea—and then in northern China and Georgia. “We thought they wouldn’t survive in colonies that overwinter,” says Jeff Pettis, a former U.S. Department of Agriculture research scientist who now heads Apimondia, an international beekeeping federation. “We know they get through the winter now,” he says. Scientists just don’t know how.

“It’s worse than varroa, and I don’t think we’ll ever be prepared fully.” —John Miller, beekeeper

One theory is that the mites disperse onto mice or rats that move into beehives during the cold months—the 1961 paper that first described tropilaelaps noted there were mites on rats in the Philippines. Scientists are exploring other overwintering theories as well. Perhaps the mites feed for brief, broodless periods on other pests in the hive, such as hive beetles and wax moths.

Another possibility, highlighted by Williams’s recent research, is that more bee larvae may persist in colder climates than previously thought, perhaps enough to feed the mites. His team has found small amounts of brood snug in wax-covered cells in hives as far north as New York State and Oregon in the winter. “My gut feeling is that these colonies might have a little bit of brood through the winter,” Williams says.

In 2022 Ramsey returned to Thailand and set up several research apiaries for what he calls his “Fight the Mite” initiative, testing different treatments to kill tropi mites. It isn’t easy. Whereas varroa mites live on adult bees for much of their life cycle, tropi mites live mostly inside brood cells, safe from most pesticides, which can’t penetrate the wax-capped hexagons.

A close-up view of a tropi mite.

But Ramsey learned from the Thai beekeepers he met on his 2019 visit that many of them had been using formic acid, the compound produced by ants that can get into capped cells. The beekeepers had been dipping paint stirrers in industrial-grade cans of the stuff and sticking the blades under hive entrances. Fumes then seeped through the wax caps and killed the mites. Ramsey experimented with various formulations and applications in 2022 and found that this method worked, although the chemical is highly volatile, caustic and difficult to apply. It’s hard on both bees and beekeepers. “Heat treatments”—heating hives to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit for two-plus hours—also took a dent out of mite populations in Ramsey’s tests.

Williams, meanwhile, has been studying “cultural techniques” for controlling the mites, such as strategic breaks in brood cycles. Beekeepers in Thailand typically keep fewer bees in relatively small colonies, much tinier than the thousands or tens of thousands that some North American commercial outfits maintain. And when mite loads get bad, some Thai beekeepers also will discard their brood completely and start over. “They’re not afraid to quite literally throw away brood frames when they have mites,” Williams says.

These strategies are difficult to apply at the scale of North American industrial apiculture. But large commercial outfits, which can keep anywhere from dozens to tens of thousands of colonies, may be able to adopt other tactics such as “indoor shedding”—storing all their hives in refrigerated sheds for a number of weeks to force an extended brood break. It’s likely that an effective approach will employ not one silver bullet but rather some combination of strategies—chemicals, heat, brood breaks—to avoid developing resistance. “You want to be able to rotate treatments to pound away at the mite,” Oliver says.

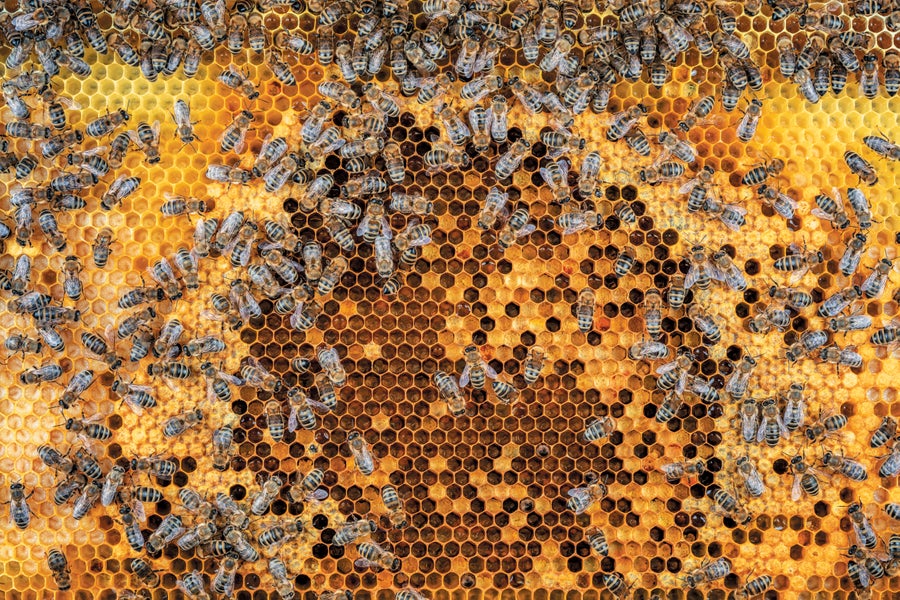

Honeybees crawl over a comb of hexagonal hive cells, some filled with honey and pollen.

These different techniques highlight the need for both varied approaches and, Ramsey believes, a varied group of scientists attacking the problem. “To study insects is to study diversity,” Ramsey says. “It is not a glitch in biology that the most successful group of animals on this planet is the most diverse group of animals. One of the key features of diversity is the capacity to solve problems in different ways.” To stave off the tropi mite, scientists will need to attack the problem from every angle they can conceive.

On an afternoon in late May 2024, Ramsey, clad in a protective suit, opened a test hive in a holding yard on the east side of Boulder. The last cold day of spring was behind us, and everything had come into bloom at once—a riot of flowering locust, linden, lilac; glowing hay fields; distant, rock-spiked mountains curving northward out of sight. Massive bumblebees flew from flower to flower on a black locust tree above us, hovering like dark blimps in the sky.

These were supposed to be Ramsey’s “pampered” bees, a control group to compare with more infested hives. They had, of course, been spared the ravages of tropi mites, which were still an ocean away. But they had been given frequent treatments for varroa mites. On the first frame Ramsey pulled, however, he saw sick bees everywhere. “This young lady clearly has a virus,” he said, noting a female’s “greasy,” prematurely bald abdomen. He pointed to a sinister dot the color of dried blood between another bee’s wings: a varroa mite. The bees were cranky, swooping and dive-bombing, and there weren’t enough brood cells on the frame. Ramsey sang to the bees in his gospel-tinged tenor, puffing at the hive with his smoker. “It seems like some of our best treatments for varroa mite are failing,” he said, examining another frame.

The American practice of beekeeping is built on abundance—stacks of bee boxes, fields of flowers, vats of honey, teeming hives and expanses of wax-capped brood. But in Thailand, where tropilaelaps has been established for decades, beekeeping often is an exercise in scarcity—small colonies, meager honey production, uncapped pupae. Beekeepers there think far less about varroa mites than they worry about tropilaelaps, which outcompeted varroa years ago.

There are so many threats facing modern honeybees—a daunting diversity, and we are ready for none of them. In 2023 the Georgia Department of Agriculture confirmed the presence of the yellow-legged hornet—Vespa velutina—in the U.S. Like the northern giant “murder” hornet found in Washington State in 2019 and declared eradicated in the U.S. last year, the yellow-legged insect is a “terrible beast,” says PAm executive director Danielle Downey. It hovers in front of beehives—a behavior called hawking—and rips the heads, abdomens and wings from returning foragers like a hunter field-dressing game. Then the hornet takes the thorax back to its nest. When the hornet first arrived in Europe, beekeepers lost 50 to 80 percent of their colonies. “The thing eats everything. One nest can eat 25 pounds of insects,” Downey says. “We’ve identified a lot of problems. How many crises can we handle?”

In the spring of 2024, when the research paper confirming tropi mites were in Europe was published, Canada suspended all imports of Ukrainian hives and queens. For now that means this route for the mite’s arrival in North America is off the table. But trade—legal or surreptitious—could start again, and with the mites’ ferocious reproduction rates, it takes only one female to infect an entire continent. So this reprieve is probably only temporary. “We know the pathway and the threat it poses,” Downey says.

A beekeeper with an infestation could spread the mite across the continent within a year; beehive die-offs would probably begin several months later. “It’s worse than varroa, and I don’t think we’ll ever be prepared fully,” Miller says.

But Ramsey and his colleagues are racing to make sure they know every option available to them—formic acid, heat treatments, rotation, brood breaks—so that when the tropilaelaps mite does, at last, inevitably arrive, they will be ready. Researchers and beekeepers, Ramsey says, are trying to murder these parasites.