A Cartoonist Finds Hope Amid the Apocalypse(s)

Peter Kuper has been publishing political cartoons and graphic novels since the 1980s, but his obsession with insects goes back even further, to when he was four years old and the cicadas emerged around his childhood home in Summit, New Jersey. “I keep this by my table,” says the cartoonist, holding a well-loved paperback copy of the classic Insects: A Guide to Familiar North American Insects up to his webcam. “This is my first insect book. All the pages are falling out.” Photo: The Revelator This year Kuper’s political cartooning and love of entomology intersected with the publication of two new environmental books — or maybe four, depending on how you count them. The first, Insectopolis: A Natural History (W.W. Norton, $35), is a graphic novel — five years in the making — about insects and the scientists who helped uncover their stories. Set after an apocalypse has wiped out all humans, the story follows the insects themselves as they travel through the New York Public Library, uncovering facts about their evolution, cultural importance, ecological roles, and more. It’s a fun, creative, colorful book that conveys Kuper’s fascination with insects and imparts more than a few lessons. Then comes Wish We Weren’t Here: Postcards From the Apocalypse (Fantagraphics, $19.99), a collection of wordless cartoons about climate change, plastic pollution, and other environmental issues originally published in the French satire magazine, Charlie Hebdo. Each one-page, four-panel strip starts with an image that slowly morphs into something more sinister and revelatory — like a drawing of an oil rig that becomes a dying junkie’s used needle. If that sounds confrontational and bleak, it is, but the book also turns the table a few times, transforming images of destruction into reasons for hope. View this post on Instagram A post shared by Peter Kuper (@kuperart) Kuper has also published two insect-themed coloring books this year, one based on Insectopolis, and another, Monarch’s Journey, adapting segments of his 2015 graphic novel, Ruins. The Revelator spoke with Kuper about these new books, the state of political cartooning, his new role as an insect conservation advocate, and what people can do to help insects and avoid despair. (This conversation has been edited lightly for brevity and style.) What’s it been like taking this insect conservation message on the road? You’re doing some book signings, some speaking tours. How are people reacting to it? It’s fulfilling the intent I had for the book, I believe, which is to get people who don’t know about insects or are afraid of insects, who generally will kill them first and ask questions later, to recognize that grocery stores would be empty of produce without insects. No chocolate, no coffee, no honey. I can tell every time I give a talk — I’ve seen the expression on people’s faces that something’s moved a little bit. In general, I try not to make my work a “scold.” I wanted to be easing people toward the correct door so that they choose the winning prize of survival. And you’re taking it to these new audiences with a Society of Illustrators show, and the bookstore audience, and the comics audience. Those aren’t necessarily always audiences who would get that conservation message. Right. And the form that it’s taking, I think, is making it a very easy pill to swallow. It’s sugar coated. I’m trying — even with Wish We Weren’t Here — to inject it with humor and have it take those kinds of mental leaps and connections that people can make in seeing something and recognizing it and maybe reconsidering something in a positive way. View this post on Instagram A post shared by Peter Kuper (@kuperart) After a lifetime of caring about insects, what did you take away from the five-year process of developing this book? My understanding of history and just coming to understand about the various extinction events that went on in the past, the essence of time and how little we humans can comprehend time. Also, just the miracle of evolution that has made the insects survive the way they have. Even something like the monarch butterfly, which I had learned about while working on Ruins — it goes through these three generations to travel 3,000 miles. The first generation’s one week, the next generation is two, and the last generation is six months. And they still don’t know how all the monarchs know how to get to this one forest in Mexico, which I also got to visit when I lived there. And there’s so many pieces of this history. I had no idea that dung beetles were the first animals — including humans — to navigate by the stars. And that they can follow the Milky Way at night to go in a straight line. And there’s so many fascinating aspects. The shine on apples comes from the lac bug, and 78 RPM records come from that same insect’s excretion. And one of the huge, fabulous aspects was reaching out to the entomologists. If I read a book, I would just look up the author online, reach out and say, “Hey, I’m working on this chapter on bees. Could you talk to me?” And every single one of them was wide open to it. In fact, slipped into Insectopolis are QR codes linking to interviews with four entomologists and the poet laureate from Mexico reading his poem about monarchs. With those interviews, I discovered that entomologists are like comic fans. The same way that comics were always considered low art, entomology was always considered low science. They were sort of put down by the people who were “all lab,” discovering DNA and poo-pooing E.O. Wilson, the ant expert at Harvard, because he was doing this dopey field work. Also, while I was at it, I was digging up entomologists and naturalists who were less known. It’s shocking how many of these people that made huge discoveries are essentially unknown. Margaret Collins, for example, was the first Black entomologist to get her Ph.D. She entered college at age 14. And she had to struggle with civil rights issues and racism and sexism to become the leading scientist on termites. I’m sure some people will be like, “Oh goody, termites.” But still, these are major areas. Architects have learned from the building structures that termites make. There are so many insects that we’ve learned from. The dragonfly has a nearly detachable head, and that’s how they figured out Velcro. Let’s shift and talk about Wish We Weren’t Here — which is a tough title to say. It twists the usual expression, “wish you were here,” and the brain does not want to go there. And I think that’s an interesting aspect of the book itself. You start with one image and twist it to another. How do you approach creating cartoons like that? My enthusiasm for wordless comics goes back to [Mad Magazine’s] “Spy vs. Spy,” which, I ironically ended up doing for 30 years. That and Sergio Aragonés’s wordless cartooning marginals and the books that he did. I get these images when I read an article. They sometimes form almost instantaneously. There’ll be a word in the article, something about “we’re gambling with climate change.” I start seeing the one-armed bandit. They just tend to form these flash images in my brain. View this post on Instagram A post shared by Peter Kuper (@kuperart) I just have to do these drawings. I read something in the paper, and I just feel like I need to have a response. And the way I can respond — aside from marching in the streets and knocking on doors, which I also do — is to do a drawing about it and share it. I was anxious to do Wish We Weren’t Here, because we’re right in the midst of even the term “climate change” being erased. So to do a whole book on climate change, it seemed like a rather vital time to do it. And though the comics in there are wordless, each page has the article that I referenced so that somebody could go and look more deeply into the subject. How does political cartooning like this compare to 10 or 20 years ago? Political cartooning has gone through such a contraction, but it’s still so powerful. Is there an audience for it? Is there an appetite for it? There’s a huge appetite for it. It’s just the delivery systems that have altered radically. You can use Instagram and social media to deliver things. I’ll post something, and, depending on the venue, it will get 100,000 likes. Or two. Do you have any advice for other people trying to use the arts or expression or protest as a way to get something out of themselves and to put some good into the world? Well, in every march I’ve been to, you get to see some of the most creative signs. They’re just people, clearly, they’re not professionals. They’re just coming up with a slogan, an image, sometimes a collage of a photo. It’s so powerful to go to a march with a sign that speaks your mind, especially if it’s with humor. Any given march is just loaded with that creative intervention, and I recommend that to everybody. View this post on Instagram A post shared by Peter Kuper (@kuperart) And please don’t stomp on insects every time you see them. Just help them out the door. If you have a lawn, you can un-mow some of it. Don’t mow, and maybe plant the occasional pollinator — just make sure that they’re appropriate pollinators and not some kind of foreign specialty plant that actually is invasive or problematic. There’s just a lot of little actions that one can take all the time — and especially right now, not falling on fear to the point where you don’t get out and protest. That’s really important, because I really feel like what we’re being pushed toward is being scared enough just to stay home and disconnect. Previously in The Revelator: Comics for Earth: Eight New Graphic Novels About Saving the Planet and Celebrating Wildlife The post A Cartoonist Finds Hope Amid the Apocalypse(s) appeared first on The Revelator.

In two powerful new graphic novels, Peter Kuper tackles climate change, disappearing insects, and other tough environmental topics — but gives us reasons to avoid despair. The post A Cartoonist Finds Hope Amid the Apocalypse(s) appeared first on The Revelator.

Peter Kuper has been publishing political cartoons and graphic novels since the 1980s, but his obsession with insects goes back even further, to when he was four years old and the cicadas emerged around his childhood home in Summit, New Jersey.

“I keep this by my table,” says the cartoonist, holding a well-loved paperback copy of the classic Insects: A Guide to Familiar North American Insects up to his webcam. “This is my first insect book. All the pages are falling out.”

This year Kuper’s political cartooning and love of entomology intersected with the publication of two new environmental books — or maybe four, depending on how you count them.

The first, Insectopolis: A Natural History (W.W. Norton, $35), is a graphic novel — five years in the making — about insects and the scientists who helped uncover their stories. Set after an apocalypse has wiped out all humans, the story follows the insects themselves as they travel through the New York Public Library, uncovering facts about their evolution, cultural importance, ecological roles, and more. It’s a fun, creative, colorful book that conveys Kuper’s fascination with insects and imparts more than a few lessons.

The first, Insectopolis: A Natural History (W.W. Norton, $35), is a graphic novel — five years in the making — about insects and the scientists who helped uncover their stories. Set after an apocalypse has wiped out all humans, the story follows the insects themselves as they travel through the New York Public Library, uncovering facts about their evolution, cultural importance, ecological roles, and more. It’s a fun, creative, colorful book that conveys Kuper’s fascination with insects and imparts more than a few lessons.

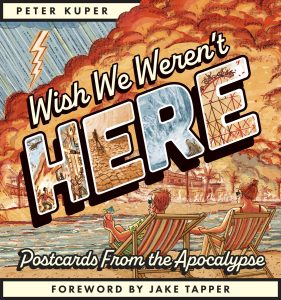

Then comes Wish We Weren’t Here: Postcards From the Apocalypse (Fantagraphics, $19.99), a collection of wordless cartoons about climate change, plastic pollution, and other environmental issues originally published in the French satire magazine, Charlie Hebdo. Each one-page, four-panel strip starts with an image that slowly morphs into something more sinister and revelatory — like a drawing of an oil rig that becomes a dying junkie’s used needle. If that sounds confrontational and bleak, it is, but the book also turns the table a few times, transforming images of destruction into reasons for hope.

Then comes Wish We Weren’t Here: Postcards From the Apocalypse (Fantagraphics, $19.99), a collection of wordless cartoons about climate change, plastic pollution, and other environmental issues originally published in the French satire magazine, Charlie Hebdo. Each one-page, four-panel strip starts with an image that slowly morphs into something more sinister and revelatory — like a drawing of an oil rig that becomes a dying junkie’s used needle. If that sounds confrontational and bleak, it is, but the book also turns the table a few times, transforming images of destruction into reasons for hope.

Kuper has also published two insect-themed coloring books this year, one based on Insectopolis, and another, Monarch’s Journey, adapting segments of his 2015 graphic novel, Ruins.

The Revelator spoke with Kuper about these new books, the state of political cartooning, his new role as an insect conservation advocate, and what people can do to help insects and avoid despair. (This conversation has been edited lightly for brevity and style.)

What’s it been like taking this insect conservation message on the road? You’re doing some book signings, some speaking tours. How are people reacting to it?

It’s fulfilling the intent I had for the book, I believe, which is to get people who don’t know about insects or are afraid of insects, who generally will kill them first and ask questions later, to recognize that grocery stores would be empty of produce without insects. No chocolate, no coffee, no honey. I can tell every time I give a talk — I’ve seen the expression on people’s faces that something’s moved a little bit.

In general, I try not to make my work a “scold.” I wanted to be easing people toward the correct door so that they choose the winning prize of survival.

And you’re taking it to these new audiences with a Society of Illustrators show, and the bookstore audience, and the comics audience. Those aren’t necessarily always audiences who would get that conservation message.

Right. And the form that it’s taking, I think, is making it a very easy pill to swallow. It’s sugar coated. I’m trying — even with Wish We Weren’t Here — to inject it with humor and have it take those kinds of mental leaps and connections that people can make in seeing something and recognizing it and maybe reconsidering something in a positive way.

After a lifetime of caring about insects, what did you take away from the five-year process of developing this book?

My understanding of history and just coming to understand about the various extinction events that went on in the past, the essence of time and how little we humans can comprehend time.

Also, just the miracle of evolution that has made the insects survive the way they have. Even something like the monarch butterfly, which I had learned about while working on Ruins — it goes through these three generations to travel 3,000 miles. The first generation’s one week, the next generation is two, and the last generation is six months. And they still don’t know how all the monarchs know how to get to this one forest in Mexico, which I also got to visit when I lived there.

And there’s so many pieces of this history. I had no idea that dung beetles were the first animals — including humans — to navigate by the stars. And that they can follow the Milky Way at night to go in a straight line.

And there’s so many fascinating aspects. The shine on apples comes from the lac bug, and 78 RPM records come from that same insect’s excretion.

And one of the huge, fabulous aspects was reaching out to the entomologists. If I read a book, I would just look up the author online, reach out and say, “Hey, I’m working on this chapter on bees. Could you talk to me?” And every single one of them was wide open to it. In fact, slipped into Insectopolis are QR codes linking to interviews with four entomologists and the poet laureate from Mexico reading his poem about monarchs.

With those interviews, I discovered that entomologists are like comic fans. The same way that comics were always considered low art, entomology was always considered low science. They were sort of put down by the people who were “all lab,” discovering DNA and poo-pooing E.O. Wilson, the ant expert at Harvard, because he was doing this dopey field work.

Also, while I was at it, I was digging up entomologists and naturalists who were less known. It’s shocking how many of these people that made huge discoveries are essentially unknown. Margaret Collins, for example, was the first Black entomologist to get her Ph.D. She entered college at age 14. And she had to struggle with civil rights issues and racism and sexism to become the leading scientist on termites.

I’m sure some people will be like, “Oh goody, termites.” But still, these are major areas. Architects have learned from the building structures that termites make. There are so many insects that we’ve learned from. The dragonfly has a nearly detachable head, and that’s how they figured out Velcro.

Let’s shift and talk about Wish We Weren’t Here — which is a tough title to say. It twists the usual expression, “wish you were here,” and the brain does not want to go there. And I think that’s an interesting aspect of the book itself. You start with one image and twist it to another. How do you approach creating cartoons like that?

My enthusiasm for wordless comics goes back to [Mad Magazine’s] “Spy vs. Spy,” which, I ironically ended up doing for 30 years. That and Sergio Aragonés’s wordless cartooning marginals and the books that he did.

I get these images when I read an article. They sometimes form almost instantaneously. There’ll be a word in the article, something about “we’re gambling with climate change.” I start seeing the one-armed bandit. They just tend to form these flash images in my brain.

I just have to do these drawings. I read something in the paper, and I just feel like I need to have a response. And the way I can respond — aside from marching in the streets and knocking on doors, which I also do — is to do a drawing about it and share it.

I was anxious to do Wish We Weren’t Here, because we’re right in the midst of even the term “climate change” being erased. So to do a whole book on climate change, it seemed like a rather vital time to do it. And though the comics in there are wordless, each page has the article that I referenced so that somebody could go and look more deeply into the subject.

How does political cartooning like this compare to 10 or 20 years ago? Political cartooning has gone through such a contraction, but it’s still so powerful. Is there an audience for it? Is there an appetite for it?

There’s a huge appetite for it. It’s just the delivery systems that have altered radically.

You can use Instagram and social media to deliver things. I’ll post something, and, depending on the venue, it will get 100,000 likes. Or two.

Do you have any advice for other people trying to use the arts or expression or protest as a way to get something out of themselves and to put some good into the world?

Well, in every march I’ve been to, you get to see some of the most creative signs. They’re just people, clearly, they’re not professionals. They’re just coming up with a slogan, an image, sometimes a collage of a photo. It’s so powerful to go to a march with a sign that speaks your mind, especially if it’s with humor. Any given march is just loaded with that creative intervention, and I recommend that to everybody.

And please don’t stomp on insects every time you see them. Just help them out the door. If you have a lawn, you can un-mow some of it. Don’t mow, and maybe plant the occasional pollinator — just make sure that they’re appropriate pollinators and not some kind of foreign specialty plant that actually is invasive or problematic.

There’s just a lot of little actions that one can take all the time — and especially right now, not falling on fear to the point where you don’t get out and protest. That’s really important, because I really feel like what we’re being pushed toward is being scared enough just to stay home and disconnect.

Previously in The Revelator:

Comics for Earth: Eight New Graphic Novels About Saving the Planet and Celebrating Wildlife

The post A Cartoonist Finds Hope Amid the Apocalypse(s) appeared first on The Revelator.