At 91, Eva Clayton Is Still Fighting for Food Justice and Farmers’ Rights

A Life of Purpose• Eva Clayton, the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress, first found her calling during the Civil Rights era, in 1963, organizing farmers. • She went on to serve five sequential terms in Congress, sitting on the Agricultural Committee throughout her tenure. • Clayton paved the way for Pigford vs. USDA, the most consequential decision for Black farmers in history. She also expanded food stamps under the 2002 Farm Bill. • In 2003, at 69, she joined the United Nations in Rome, and for several years led a global anti-hunger effort. • While pursuing her political career, Clayton raised four children with her husband, a lawyer. Eva Clayton was outraged. It was late October, and the North Carolina legislature had just introduced a swiftly moving plan to redraw the congressional map for the First District, where she lived, to dilute Black voting power and favor Republicans. As the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress, elected to the House in 1992 to serve the district now under threat, Clayton had broken the racial barrier, and in every election since, constituents there had elected a Black Democrat to represent them. The new maps, developed mid-decade at the urging of Donald Trump, cut majority-Black counties out of the First District and lumped them into the conservative Third District. This virtually ensured that Clayton’s district could not elect a Democrat, especially a Black Democrat, again. Never one to stay silent, 91-year-old Clayton put on a gray suit, arranged a pink-and-green scarf around her shoulders, and rode an hour and a half south from her home in rural Warren County to Raleigh. Clayton walks with a metal cane, and at five feet, she wasn’t much taller than the wooden podium in the legislative office building’s meeting room. But her tone was fierce as she addressed the lawmakers. While some may not have heard of her, within her home state, Clayton is a towering figure in food politics. “Shame on this General Assembly,” she said, an edge to her deep, smooth voice, “for silencing the will of the people in northeastern North Carolina, a true swing district that reflects the diversity of the state . . . . What you are doing today means you are against democracy.” While some may not have heard of her, within her home state, Clayton is a towering figure in food politics—someone who has transformed people’s lives for the better on the local, regional, national, and international levels. After her Congressional win in the early ’90s, Clayton went on to serve five terms, sitting on the Agriculture Committee her entire tenure and fighting for food access and the rights of small farmers. In 1999, she was instrumental in pushing through the historic Pigford discrimination lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which awarded the plaintiffs, all Black farmers, more than $1 billion—the largest civil rights settlement ever awarded at that time. She also expanded food stamps to include documented immigrants in the 2002 Farm Bill, helping strengthen food security for thousands of families. After her political service, Clayton, then 69, took her work to a global level, leading the United Nations in an effort to reduce hunger worldwide. And now, she helps guide the Eva Clayton Rural Food Institute, a regional nonprofit that increases food access for rural families and small farmers in her community. On that October day in Raleigh, as the Assembly moved to dismantle the district she had championed for most of her life, an interviewer for the North Carolina Black Alliance caught up to her in the hallway. “She is a powerful force, but also a gentle force. She has the soul of a great warrior.” Clayton had more to say, now speaking directly to her community, mired in the ongoing government shutdown: “They’re taking so many things away, taking food from hungry people, taking help from people who need help . . . and taking the right to determine who represents you, all at the same time,” she said, sweeping her arm for emphasis. “In spite of that, folks, stand up. Speak up for democracy. We need you.” The following day, despite Clayton’s impassioned argument, the legislature formally approved the new maps, and the First District is predicted to go Republican in the 2026 election. Virginia farmer Michael Carter compares Clayton to leaders before and after the Antebellum Era, motivated not by ego but by doing what was right. “She is a powerful force, but also a gentle force,” he says. “She has the soul of a great warrior.” Finding Her Footing Born in 1934, Clayton was raised in Savannah and Augusta, Georgia, by a charismatic, outgoing father who worked as a life insurance agent (“he could sell life insurance to a tombstone!” says Clayton) and a stern but loving mother who, as a PTA president, organized daily fresh fruit for Clayton’s school, which lacked even a cafeteria. It was Clayton’s first glimpse of food justice, something she came to see later as a foreshadowing of her own hunger relief efforts. Clayton at home in Savannah, Georgia, after her kindergarten graduation. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton) As she matured, Clayton began questioning the racism of the segregated South, and a spiritual awakening at a bible camp during high school gave her an abiding approach to countering injustice. “I understood Christ was for love, and I could show that,” she said. “I could be a beacon.” Intent on becoming a medical missionary in Africa, Clayton studied biology at Johnson C. Smith University, a historically Black college in Charlotte. There she met her future husband, Theaoseus Theaboyd “T.T.” Clayton, a charming senior from a farming family. Both went on to earn master’s degrees—he in law, she in biology and general science. Between getting her degrees, Clayton traveled to Chicago to intern with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker peace and social justice organization. Their seminars and forums helped shape her worldview. “They tried to teach me how to speak up against the policy of the person without taking down the person,” she said. “That experience sharpened my insight on how to be engaged with people, not only in terms of presenting [ideas to them] but also listening. The Quakers have a sense of the long view . . . They’re committed not only to peace but to peaceful ways.” Building a Voice for the First District When I met Clayton recently at her Warren County home, a tidy, split-level ranch on the shores of Lake Gaston, she welcomed me in with a broad smile and the same direct gaze I’d seen in her many Congressional portraits. Her once-dark hair was cropped short and mostly white, and she was well put together in a navy striped dress shirt, round silver necklace, and dangly silver earrings. She had been sorting through papers and photographs to make space for her son Martin and his wife, who were about to move in, but the walls of her basement den were still covered in pictures of herself with presidents, dignitaries, and Pope John Paul II. “It’s like spending the night in the Eva Clayton Museum,” her daughter Joanne told me later, chuckling. “I know what MLK’s children must have felt like.” Most of her collection, though, was in her sunroom, packed into file boxes scattered across the floor. Clayton delightedly unearthed an artifact: a newspaper article about a voter registration project she organized in Warren County, back in 1963. That summer changed the course of her life—and the future of her district. Clayton, T.T., and their two young children had moved to the county the year before, when T.T. accepted a law partnership in the town of Warrenton, creating the first integrated firm in the state’s history. Proud to finally have a Black lawyer in town, the community embraced the Clayton family. And Clayton found her small-town neighbors—who sometimes paid her husband in meat from their farms—to be warm and kind. “I fell in love with them, and they showed the love to me too,” she said. The countryside around Warrenton was lush, but poor. Two out of three people were Black, nine out of ten lived on farms, and many were sharecroppers who had to turn over a portion of their monthly income to their white landlords. With the Voting Rights Act of 1965 still a few years from passing and Southern states still employing tactics like literacy tests to suppress votes, few Black people in the area were registered to vote, and none served in government. Farmers harvesting tobacco in the Warren County Hecks Grove community, 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) In 1963, Clayton helped drive student volunteers to isolated pockets of Warren County to try to convince rural residents, including tenant farmers like the woman in this photo, to register to vote. “Without knowing,” Clayton said recently, “I was teaching myself that I could be engaged with people, I could lead.” (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) At 29, Clayton quickly realized that, rather than pursue her dream of being a missionary in Africa, she could help and heal her new community instead. She decided to launch a voter registration project, inviting the Quaker group she had interned with in Chicago to help. Fourteen college students and three leaders—the first integrated group the area had ever seen—moved into a six-room apartment above Brown’s Superette grocery store downtown. Over the summer, the volunteers held workshops at rural churches and community centers throughout the region to educate would-be voters about the Constitution and the voting process, even holding mock elections. Clayton helped the young volunteers understand local customs and took them to buy groceries. When the segregated laundromat kicked them out, she let them do laundry at her house, and when the Klan showed up outside their downtown apartment to intimidate them, she invited them over to sleep on her floor. In her puttery Renault, she drove the volunteers through the tobacco, cotton, and peanut fields of Warren, Franklin, and Vance counties to find unregistered voters recommended by church and community leaders. Meeting tenant farmers in bare-bones wooden houses with no electricity or running water was eye-opening for Clayton—“I didn’t know people lived that way,” she said—and the task was tall: to persuade them to overcome their lack of confidence, fear, or distrust of the political system and take action. A voter education workshop at Brookston Baptist Church, Warren County, 1963. To build familiarity and confidence with the voting process, student volunteers held several mock elections, where they playacted as candidates and participants cast their ballots. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) That summer, Clayton discovered ways of working with people that she would use throughout her career. She learned that the farmers were most likely to sign up and vote when she used “we,” asking them to join her rather than telling them what to do or doing it for them. “Part of my strategy in life has been [to say] not that I’m doing this for your good, but we’re doing it together,” she said. “People bring their strength when they know they’re needed.” By the summer’s end, the group had conducted more than 30 workshops throughout the region. When the Claytons moved to Warrenton in 1962, the town had a newspaper, a movie theater, two grocery stores, and a department store. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) Like everywhere in the South at the time, segregation was the rule in Warrenton in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) Clayton then turned her sights to matters in town, organizing a protest against the sandwich shop that her husband’s law partner ran downstairs from their office on Market Street. A favorite spot in town for Black and white people alike, the counter served hot dogs, hamburgers, barbecue, and milk shakes—and everyone knew what the partition along the counter was for. “It needed to go,” Clayton said firmly. “I mean, if you’re integrated upstairs, why couldn’t you be integrated downstairs?” T.T. and his law partner were working upstairs when they looked out the front windows and noticed Clayton in a group of picketers on the sidewalk. “My husband’s partner said, ‘Clayton, is that your wife down there? What’s she doing? Tell her not to do that!’ [And my husband said,] ‘YOU tell her!’” Soon after that, Clayton said, “The partition left—it quietly went away.” It was her first time standing up against injustice. “I thought to myself that I had talent, and I had an obligation to try to make a difference,” she said. “And I still feel that way, if I’m being honest with you.” Clayton Goes to Congress Clayton took her first run at Congress in 1968, purely to encourage people to register to vote. “I ran and lost royally,” Clayton said. “But I registered people all throughout the district, and that was the beauty of it.” Voter registration increased by 25 percent in Warren County—the highest increase until then and since. “I saw, in many small towns where they had a majority, Blacks became mayors.” They began to hold other offices too, she added. “They saw the strength of their constituency.” Clayton dedicated the next couple of decades to working in local and state politics, all while she and T.T. raised a family of now four children. One of her most notable efforts was her support of the landmark Warren County toxic-waste protests in 1982, considered the beginning of the national environmental justice movement. Clayton put up bond for those arrested. Hundreds participated in the protest, and according to Cosmos George, former president of the Warren County NAACP, Clayton’s extensive voter registration work over the years was a big reason why. “To me, the major thing she did was christen Warren County to become politically aware,” he said. “To me, the major thing she did was christen Warren County to become politically aware.” Then, 24 years after her first national run, in 1992, Clayton entered the Democratic primary to represent those neighbors, the people of North Carolina’s First Congressional District. “The Best for the First,” her campaign wrote on T-shirts, plaques, and the sides of their cars. Despite her optimism, racism shadowed the campaign—at one point, a man spat toward her as she shook hands with constituents. Joanne remembers her mother rising above the disrespect and never reacting to it, summing up her attitude with, “You want more [from people], but you’re ready for it.” Ultimately, Clayton prevailed, advancing to the national stage and becoming the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress. “The Lord is good,” she told The Virginian-Pilot as she moved ahead of her Republican rival. A Fierce Advocate for Farmers Soon after Clayton took office, she was elected president of her freshman class—and earned a spot on the Agricultural Committee, the most effective way she saw to serve her constituents. At the time, the Ag Committee was an old-boys club; their dismissive attitude toward her made her angry and indignant. “They tolerated me,” Clayton told a Congressional historian for a recording in 2015, frustration in her voice. “They treated me as an outsider; I had to prove to them I was worthy of negotiating with.” Eva Clayton, top right, on the floor of Congress in the 1990s. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton) Because the committee during most of her tenure was almost all white and controlled by Republicans, Clayton had to quickly learn how to work with people who didn’t agree with her. “They need you sometimes, and you need them,” she said in an interview with PBS. “You have to begin to understand the value of being able to communicate with a variety of people, not just your friends—and respect their views . . . because you want to persuade them to respect your views.” Saxby Chambliss, a Republican from Georgia who served in the House from 1995 to 2003 before becoming a Senator, worked with Clayton on the Ag Committee and negotiated with her on two farm bills. “Eva is a really nice lady, but she was forceful in her opinion about the issues she cared about,” Chambliss remembered. “Republicans were in control, so when it came to her issues, she knew she was going uphill. But she never wavered.” Ellen Teller, who has worked with the Washington, D.C.–based Food Research and Action Center since 1986 and met with Clayton frequently during her years on the Ag Committee, remembered how Clayton invoked “this air of authority and knowledge tempered with just the right amount of intimidation . . . Being one of the first African American women on the House Ag Committee, she needed to be collaborative and wonderful to work with. But she wasn’t going to let those guys walk all over her.” In her third term, Clayton was essential to advancing one of the most consequential decisions for farmers in U.S. history. In 1997, Timothy Pigford, a Black soybean and corn farmer in Cumberland County, North Carolina, filed a class-action lawsuit charging the USDA with racial discrimination in its lending and assistance programs. The 400 plaintiffs held that the local county commissioners charged with doling out federal money at the beginning of each growing season—which they relied on to purchase seed, fertilizer, and farm equipment—would delay or deny their applications based on their race or apply more restrictions to the money. Many of the plaintiffs faced financial ruin and lost their farms as a result. When Pigford first filed, the plaintiffs ran up against the Equal Credit Opportunity’s statute of limitations, which excluded them from pursuing compensation for discrimination more than two years in the past. The Ag Committee—which was predominantly white—refused to vote on removing the limiting statute, which would have allowed the lawsuit to proceed. Clayton was determined that these farmers have a chance to seek justice. She found a strategy mentor in John Conyers, a Black Democrat from Michigan who was the ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee. He advised her to try introducing the removal of the statute of limitations as an amendment on the floor of the Appropriations Committee. When the agriculture appropriations bill came up, Clayton asked the speaker for permission to introduce the amendment, which he granted her. Not wanting Clayton’s amendment to stand in the way of passing their budget, the members of her committee voted for it. “I thank God for Conyers,” Clayton said. “That’s how we got the statute of limitations removed,” she said, enabling the historic lawsuit to proceed. It grew to include more than 22,700 plaintiffs across the South, seeking restitution for decades of discrimination that had led to massive land loss among Black farming families. In 1999, a federal judge approved a settlement agreement for more than $1 billion. Just over 15,500 claimants have received compensation, most getting $50,000, though the disbursal of funds has been far from perfect and many believe the per-farmer sum is not nearly enough to compensate for the damage. For farmers like Warren County’s Arthur Brown—who was part of the second round of Pigford claims—Clayton was a critical voice in Washington. “Eva Clayton spoke for him,” Brown’s son Patrick said. “She went to the local town halls and got information [from farmers] to carry back to Washington to advocate on their behalf.” Pigford II claims were settled in 2010, for an additional $1.25 billion. Clayton said she made a point of meeting with the people in her district at least six times a year, and more often during extended recesses. Hearing directly from those impacted by policies, she said, helped strengthen her arguments and helped her see, as she put it, “where you’re being effective and where there’s possibility.” She also pushed for qualified Black people to lead at least four USDA agencies in North Carolina, including the Farm Service Agency and the Risk Management Agency, said Archie Hart, a special assistant to the North Carolina commissioner of agriculture. For the first time, this opened the door for Black farmers to participate in programs like crop insurance and environmental incentive programs. Between 1978 and 2000, Black farmers in North Carolina had lost 70 percent of their land, Hart said. Clayton’s efforts to connect farmers to federal assistance, he said, “stopped the bleeding.” Protecting and Expanding Federal Food Assistance Clayton was equally dedicated to food access. The welfare reform law that Republicans passed in 1996 made deep cuts to the food stamp program, lowering the maximum benefit, eliminating eligibility for many documented immigrants, and adding work requirements. In the years that followed, Clayton played a key role in the movement to restore food stamps, said Teller. As the senior Democrat on the Ag subcommittee responsible for nutrition programs, she helped author the 2002 Farm Bill which, among other things, expanded food stamp eligibility to documented immigrants in the U.S. and to their children, providing vital assistance to an additional one million legal immigrants working for a better life. Clayton meets with Newt Gingrich, speaker of the House, in the mid 1990s. “FEED the FOLKS” was her campaign to protect the federal school lunch program from drastic cuts proposed by Republicans. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton) Former Rep. Chambliss remembers Clayton sharing the lived experiences of her constituents with the committee. “Because she represented a poor district, she had a lot of anecdotes she could use to back up her position” that the government needed to strengthen its social safety net, he said. As a negotiator, he said, she was very effective: “Just look at the numbers—in the ’02 bill, we bumped up food stamps pretty good.” As Clayton advocated for nutrition assistance, she consistently countered the prevailing stereotypes about Black people, said Hart of North Carolina’s agriculture department. “A lot of other cultures have you down as ‘Black people are just lazy,’” he said. “There are so many prejudices, and she was able to say, ‘Let me explain my culture. People aren’t asking for a handout—they’re asking for their God-given right as citizens.’” Balancing Politics and Motherhood Clayton manages to combine intense focus and determination with grandmotherly warmth and a quick sense of humor. During my visits, she called me “darling,” chatted easily about her grandkids and garden, ribbed me for asking too many questions, and once offered me lunch from her fridge so I wouldn’t drive home on an empty stomach. Throughout her career, she was raising her daughter and three sons in rural Warren County. As they grew, she drove them to piano, dance, karate, and basketball practices in nearby towns, Joanne remembers, and when they got sick, she would put washcloths on their foreheads, rub menthol on their chests, and hum them to sleep. Clayton at her house on Lake Gaston, North Carolina. While pursuing a political career, she and her husband raised four children; she now has six grandchildren, too. (Photo credit: Christina Cooke) While Clayton expressed her love in many ways, cooking was not one of them, Joanne continues. “My mother could not cook with a damn,” she said, laughing. (Her father, on the other hand, was excellent in the kitchen.) “My mother burnt toast so much that my father would order burnt toast in restaurants. You know you’re a good husband when you accept defeat: ‘She can’t cook, and not only do I have burnt toast, I want burnt toast. That’s how much I love you, baby.’” Clayton’s feeling of responsibility to her community often drew her away from her family. She was consistently busy with meetings and functions. And sometimes, her drive to better the world came at the expense of her children’s feelings. In 1963, T.T. filed a lawsuit to desegregate the Warren County Schools, and the Claytons sent Joanne to first grade at the all-white Mariam Boyd Elementary. Joanne simply “got through it,” she said, as the other kids subjected her to spitballs and other insults. “I probably should have been more concerned about my kids, but I thought they could handle it,” said Clayton, who sent Theaoseus Jr. and Martin to the same school later. In preparing her kids beforehand, Clayton focused more on the courage required than the harm they might face. Despite the difficulty, Clayton is exceedingly proud to have played a part in integrating the schools and feels the hardship her kids endured was worth it. “Nobody really harmed them,” she said. “They were isolated, I’m sure of that. But they did all right.” Combatting Hunger Worldwide—and at Home Clayton had long said she would serve in Congress for only 10 years. And when that anniversary arrived in 2002, she stepped aside. A year later, she was appointed the assistant director-general of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, based in Rome—fulfilling, in a way, her childhood dream of helping others abroad. At the FAO, she worked on a coalition to cut world hunger in half by 2015, a goal set at the 1996 World Food Summit. The group did not meet its ambitious goal, but, said Clayton, “we organized alliances and partnerships in 24 countries and got people to see the value of working together. That is one thing I still look back on with great pride.” Clayton met with Pope John Paul II to engage the Catholic church in the United Nations effort to halve world hunger, circa 2004. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton) Various international organizations, including Rotary International, signed on to the hunger-reduction effort. Clayton met with the pope to get the Catholic church involved, and groups like Bread for the World, a U.S.-based Christian anti-hunger advocacy organization, enlisted as well. Though she is back in Warren County now, Clayton has not given up on the wish to make a dent in food insecurity. “I’ll go to my grave not having fulfilled the goal,” she said, “but I do want to end my existence still trying.” And that is exactly what she is doing, lending her support to a food-security effort closer to home. In 2023, the Green Rural Redevelopment Organization (GRRO), a nonprofit that tackles poverty, food insecurity, and chronic disease in north-central North Carolina, launched a food justice network and named it the Eva Clayton Rural Food Institute to build on her legacy. Clayton is focusing on food in her own life too. T.T. died in 2019, a blow to her heart and spirit. In his absence, she has started teaching herself to cook. “Now I’m wanting to cook the special things,” she said, “like salmon cakes for breakfast.” A Life of Purpose Clayton, who still speaks publicly on a regular basis, stands in front of the stately red-brick county courthouse in Warrenton in a mid-calf pink and navy dress. The town is celebrating Juneteenth today, and its leaders have requested she speak. “She looks good!” the woman beside me whispers to her friend as Clayton begins. Clayton speaking at the Juneteenth celebration at the Warrenton county courthouse this year. (Photo Credit: Christina Cooke) “This is a day of freedom we are celebrating,” Clayton tells the crowd. “But freedom is really not free.” Citizens are the most vital part of a democracy—more important that elected leaders, she continues. “Citizens elect officials. But we elect them and leave them; we don’t hold them accountable.” Engage with your elected officials, she entreats, pointing her cane in the air. “Freedom requires us collectively to walk forward.” She hands off the mic to a vigorous round of applause and cheers. After mingling and saying goodbye to well-wishers, Clayton heads toward her car parked a few blocks from the courthouse, making her way with care down the uneven sidewalk. On the left, its façade chipped and faded, stands the building that housed T.T.’s law office and his partner’s sandwich shop, where she protested segregation more than 60 years ago. Clayton says she feels grateful to have the desire to still be involved. “At some point, people say, ‘I don’t want to be bothered with certain things,’” she says. “But I do want to be bothered with things. I think that’s a blessing, to live with a purpose.” The post At 91, Eva Clayton Is Still Fighting for Food Justice and Farmers’ Rights appeared first on Civil Eats.

As the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress, elected to the House in 1992 to serve the district now under threat, Clayton had broken the racial barrier, and in every election since, constituents there had elected a Black Democrat to represent them. The new maps, developed mid-decade at the urging of Donald […] The post At 91, Eva Clayton Is Still Fighting for Food Justice and Farmers’ Rights appeared first on Civil Eats.

• Eva Clayton, the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress, first found her calling during the Civil Rights era, in 1963, organizing farmers.

• She went on to serve five sequential terms in Congress, sitting on the Agricultural Committee throughout her tenure.

• Clayton paved the way for Pigford vs. USDA, the most consequential decision for Black farmers in history. She also expanded food stamps under the 2002 Farm Bill.

• In 2003, at 69, she joined the United Nations in Rome, and for several years led a global anti-hunger effort.

• While pursuing her political career, Clayton raised four children with her husband, a lawyer.

Eva Clayton was outraged. It was late October, and the North Carolina legislature had just introduced a swiftly moving plan to redraw the congressional map for the First District, where she lived, to dilute Black voting power and favor Republicans.

As the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress, elected to the House in 1992 to serve the district now under threat, Clayton had broken the racial barrier, and in every election since, constituents there had elected a Black Democrat to represent them.

The new maps, developed mid-decade at the urging of Donald Trump, cut majority-Black counties out of the First District and lumped them into the conservative Third District. This virtually ensured that Clayton’s district could not elect a Democrat, especially a Black Democrat, again.

Never one to stay silent, 91-year-old Clayton put on a gray suit, arranged a pink-and-green scarf around her shoulders, and rode an hour and a half south from her home in rural Warren County to Raleigh.

Clayton walks with a metal cane, and at five feet, she wasn’t much taller than the wooden podium in the legislative office building’s meeting room. But her tone was fierce as she addressed the lawmakers.

While some may not have heard of her, within her home state, Clayton is a towering figure in food politics.

“Shame on this General Assembly,” she said, an edge to her deep, smooth voice, “for silencing the will of the people in northeastern North Carolina, a true swing district that reflects the diversity of the state . . . . What you are doing today means you are against democracy.”

While some may not have heard of her, within her home state, Clayton is a towering figure in food politics—someone who has transformed people’s lives for the better on the local, regional, national, and international levels. After her Congressional win in the early ’90s, Clayton went on to serve five terms, sitting on the Agriculture Committee her entire tenure and fighting for food access and the rights of small farmers.

In 1999, she was instrumental in pushing through the historic Pigford discrimination lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which awarded the plaintiffs, all Black farmers, more than $1 billion—the largest civil rights settlement ever awarded at that time. She also expanded food stamps to include documented immigrants in the 2002 Farm Bill, helping strengthen food security for thousands of families.

After her political service, Clayton, then 69, took her work to a global level, leading the United Nations in an effort to reduce hunger worldwide. And now, she helps guide the Eva Clayton Rural Food Institute, a regional nonprofit that increases food access for rural families and small farmers in her community.

On that October day in Raleigh, as the Assembly moved to dismantle the district she had championed for most of her life, an interviewer for the North Carolina Black Alliance caught up to her in the hallway.

“She is a powerful force, but also a gentle force. She has the soul of a great warrior.”

Clayton had more to say, now speaking directly to her community, mired in the ongoing government shutdown: “They’re taking so many things away, taking food from hungry people, taking help from people who need help . . . and taking the right to determine who represents you, all at the same time,” she said, sweeping her arm for emphasis. “In spite of that, folks, stand up. Speak up for democracy. We need you.”

The following day, despite Clayton’s impassioned argument, the legislature formally approved the new maps, and the First District is predicted to go Republican in the 2026 election.

Virginia farmer Michael Carter compares Clayton to leaders before and after the Antebellum Era, motivated not by ego but by doing what was right. “She is a powerful force, but also a gentle force,” he says. “She has the soul of a great warrior.”

Finding Her Footing

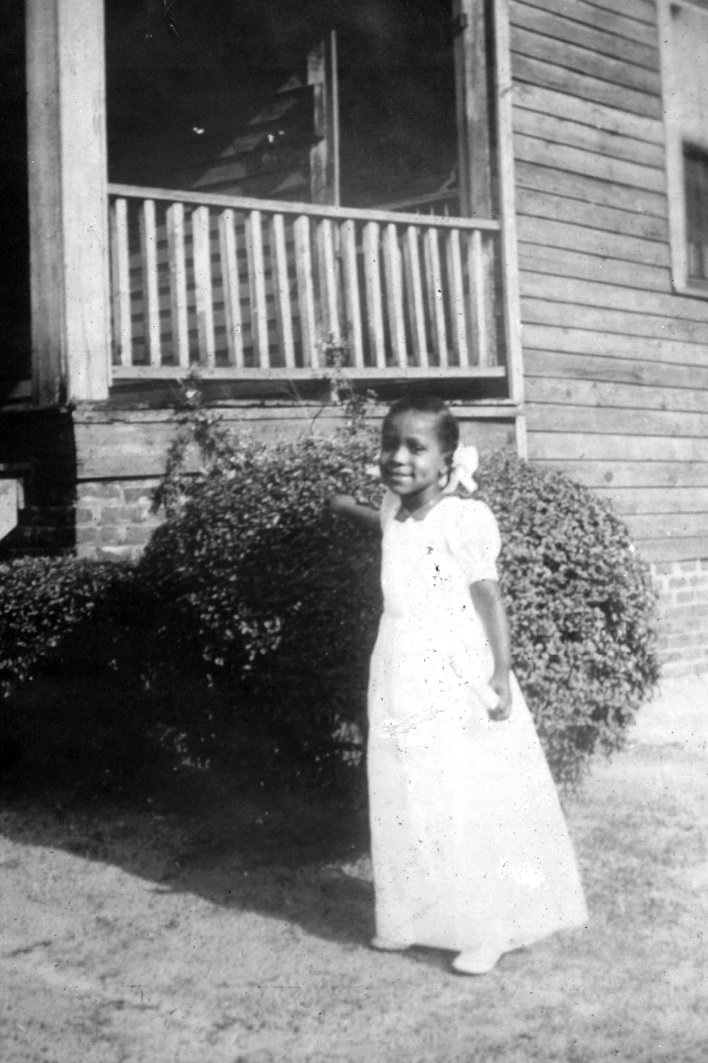

Born in 1934, Clayton was raised in Savannah and Augusta, Georgia, by a charismatic, outgoing father who worked as a life insurance agent (“he could sell life insurance to a tombstone!” says Clayton) and a stern but loving mother who, as a PTA president, organized daily fresh fruit for Clayton’s school, which lacked even a cafeteria. It was Clayton’s first glimpse of food justice, something she came to see later as a foreshadowing of her own hunger relief efforts.

Clayton at home in Savannah, Georgia, after her kindergarten graduation. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton)

As she matured, Clayton began questioning the racism of the segregated South, and a spiritual awakening at a bible camp during high school gave her an abiding approach to countering injustice. “I understood Christ was for love, and I could show that,” she said. “I could be a beacon.”

Intent on becoming a medical missionary in Africa, Clayton studied biology at Johnson C. Smith University, a historically Black college in Charlotte. There she met her future husband, Theaoseus Theaboyd “T.T.” Clayton, a charming senior from a farming family. Both went on to earn master’s degrees—he in law, she in biology and general science.

Between getting her degrees, Clayton traveled to Chicago to intern with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker peace and social justice organization. Their seminars and forums helped shape her worldview.

“They tried to teach me how to speak up against the policy of the person without taking down the person,” she said. “That experience sharpened my insight on how to be engaged with people, not only in terms of presenting [ideas to them] but also listening. The Quakers have a sense of the long view . . . They’re committed not only to peace but to peaceful ways.”

Building a Voice for the First District

When I met Clayton recently at her Warren County home, a tidy, split-level ranch on the shores of Lake Gaston, she welcomed me in with a broad smile and the same direct gaze I’d seen in her many Congressional portraits. Her once-dark hair was cropped short and mostly white, and she was well put together in a navy striped dress shirt, round silver necklace, and dangly silver earrings.

She had been sorting through papers and photographs to make space for her son Martin and his wife, who were about to move in, but the walls of her basement den were still covered in pictures of herself with presidents, dignitaries, and Pope John Paul II.

“It’s like spending the night in the Eva Clayton Museum,” her daughter Joanne told me later, chuckling. “I know what MLK’s children must have felt like.”

Most of her collection, though, was in her sunroom, packed into file boxes scattered across the floor. Clayton delightedly unearthed an artifact: a newspaper article about a voter registration project she organized in Warren County, back in 1963.

That summer changed the course of her life—and the future of her district.

Clayton, T.T., and their two young children had moved to the county the year before, when T.T. accepted a law partnership in the town of Warrenton, creating the first integrated firm in the state’s history. Proud to finally have a Black lawyer in town, the community embraced the Clayton family.

And Clayton found her small-town neighbors—who sometimes paid her husband in meat from their farms—to be warm and kind. “I fell in love with them, and they showed the love to me too,” she said.

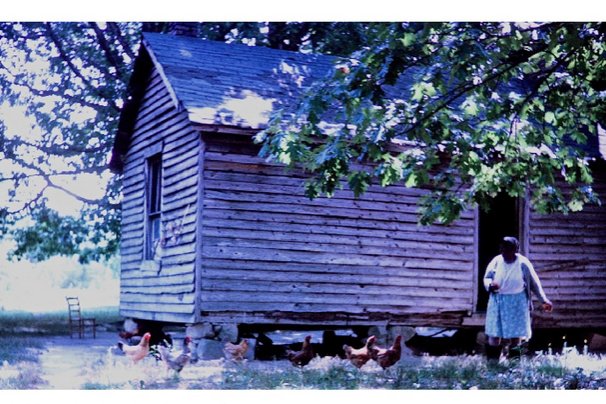

The countryside around Warrenton was lush, but poor. Two out of three people were Black, nine out of ten lived on farms, and many were sharecroppers who had to turn over a portion of their monthly income to their white landlords. With the Voting Rights Act of 1965 still a few years from passing and Southern states still employing tactics like literacy tests to suppress votes, few Black people in the area were registered to vote, and none served in government.

Farmers harvesting tobacco in the Warren County Hecks Grove community, 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan)

In 1963, Clayton helped drive student volunteers to isolated pockets of Warren County to try to convince rural residents, including tenant farmers like the woman in this photo, to register to vote. “Without knowing,” Clayton said recently, “I was teaching myself that I could be engaged with people, I could lead.” (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan)

At 29, Clayton quickly realized that, rather than pursue her dream of being a missionary in Africa, she could help and heal her new community instead. She decided to launch a voter registration project, inviting the Quaker group she had interned with in Chicago to help.

Fourteen college students and three leaders—the first integrated group the area had ever seen—moved into a six-room apartment above Brown’s Superette grocery store downtown. Over the summer, the volunteers held workshops at rural churches and community centers throughout the region to educate would-be voters about the Constitution and the voting process, even holding mock elections.

Clayton helped the young volunteers understand local customs and took them to buy groceries. When the segregated laundromat kicked them out, she let them do laundry at her house, and when the Klan showed up outside their downtown apartment to intimidate them, she invited them over to sleep on her floor.

In her puttery Renault, she drove the volunteers through the tobacco, cotton, and peanut fields of Warren, Franklin, and Vance counties to find unregistered voters recommended by church and community leaders. Meeting tenant farmers in bare-bones wooden houses with no electricity or running water was eye-opening for Clayton—“I didn’t know people lived that way,” she said—and the task was tall: to persuade them to overcome their lack of confidence, fear, or distrust of the political system and take action.

A voter education workshop at Brookston Baptist Church, Warren County, 1963. To build familiarity and confidence with the voting process, student volunteers held several mock elections, where they playacted as candidates and participants cast their ballots. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) That summer, Clayton discovered ways of working with people that she would use throughout her career. She learned that the farmers were most likely to sign up and vote when she used “we,” asking them to join her rather than telling them what to do or doing it for them. “Part of my strategy in life has been [to say] not that I’m doing this for your good, but we’re doing it together,” she said. “People bring their strength when they know they’re needed.” By the summer’s end, the group had conducted more than 30 workshops throughout the region. When the Claytons moved to Warrenton in 1962, the town had a newspaper, a movie theater, two grocery stores, and a department store. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan)

Like everywhere in the South at the time, segregation was the rule in Warrenton in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Judith Beil Vaughan) Clayton then turned her sights to matters in town, organizing a protest against the sandwich shop that her husband’s law partner ran downstairs from their office on Market Street. A favorite spot in town for Black and white people alike, the counter served hot dogs, hamburgers, barbecue, and milk shakes—and everyone knew what the partition along the counter was for. “It needed to go,” Clayton said firmly. “I mean, if you’re integrated upstairs, why couldn’t you be integrated downstairs?” T.T. and his law partner were working upstairs when they looked out the front windows and noticed Clayton in a group of picketers on the sidewalk. “My husband’s partner said, ‘Clayton, is that your wife down there? What’s she doing? Tell her not to do that!’ [And my husband said,] ‘YOU tell her!’” Soon after that, Clayton said, “The partition left—it quietly went away.” It was her first time standing up against injustice. “I thought to myself that I had talent, and I had an obligation to try to make a difference,” she said. “And I still feel that way, if I’m being honest with you.” Clayton took her first run at Congress in 1968, purely to encourage people to register to vote. “I ran and lost royally,” Clayton said. “But I registered people all throughout the district, and that was the beauty of it.” Voter registration increased by 25 percent in Warren County—the highest increase until then and since. “I saw, in many small towns where they had a majority, Blacks became mayors.” They began to hold other offices too, she added. “They saw the strength of their constituency.” Clayton dedicated the next couple of decades to working in local and state politics, all while she and T.T. raised a family of now four children. One of her most notable efforts was her support of the landmark Warren County toxic-waste protests in 1982, considered the beginning of the national environmental justice movement. Clayton put up bond for those arrested. Hundreds participated in the protest, and according to Cosmos George, former president of the Warren County NAACP, Clayton’s extensive voter registration work over the years was a big reason why. “To me, the major thing she did was christen Warren County to become politically aware,” he said. “To me, the major thing she did was christen Warren County to become politically aware.” Then, 24 years after her first national run, in 1992, Clayton entered the Democratic primary to represent those neighbors, the people of North Carolina’s First Congressional District. “The Best for the First,” her campaign wrote on T-shirts, plaques, and the sides of their cars. Despite her optimism, racism shadowed the campaign—at one point, a man spat toward her as she shook hands with constituents. Joanne remembers her mother rising above the disrespect and never reacting to it, summing up her attitude with, “You want more [from people], but you’re ready for it.” Soon after Clayton took office, she was elected president of her freshman class—and earned a spot on the Agricultural Committee, the most effective way she saw to serve her constituents. At the time, the Ag Committee was an old-boys club; their dismissive attitude toward her made her angry and indignant. “They tolerated me,” Clayton told a Congressional historian for a recording in 2015, frustration in her voice. “They treated me as an outsider; I had to prove to them I was worthy of negotiating with.” Because the committee during most of her tenure was almost all white and controlled by Republicans, Clayton had to quickly learn how to work with people who didn’t agree with her. “They need you sometimes, and you need them,” she said in an interview with PBS. “You have to begin to understand the value of being able to communicate with a variety of people, not just your friends—and respect their views . . . because you want to persuade them to respect your views.” Saxby Chambliss, a Republican from Georgia who served in the House from 1995 to 2003 before becoming a Senator, worked with Clayton on the Ag Committee and negotiated with her on two farm bills. “Eva is a really nice lady, but she was forceful in her opinion about the issues she cared about,” Chambliss remembered. “Republicans were in control, so when it came to her issues, she knew she was going uphill. But she never wavered.” Ellen Teller, who has worked with the Washington, D.C.–based Food Research and Action Center since 1986 and met with Clayton frequently during her years on the Ag Committee, remembered how Clayton invoked “this air of authority and knowledge tempered with just the right amount of intimidation . . . Being one of the first African American women on the House Ag Committee, she needed to be collaborative and wonderful to work with. But she wasn’t going to let those guys walk all over her.” In her third term, Clayton was essential to advancing one of the most consequential decisions for farmers in U.S. history. In 1997, Timothy Pigford, a Black soybean and corn farmer in Cumberland County, North Carolina, filed a class-action lawsuit charging the USDA with racial discrimination in its lending and assistance programs. The 400 plaintiffs held that the local county commissioners charged with doling out federal money at the beginning of each growing season—which they relied on to purchase seed, fertilizer, and farm equipment—would delay or deny their applications based on their race or apply more restrictions to the money. Many of the plaintiffs faced financial ruin and lost their farms as a result. When Pigford first filed, the plaintiffs ran up against the Equal Credit Opportunity’s statute of limitations, which excluded them from pursuing compensation for discrimination more than two years in the past. The Ag Committee—which was predominantly white—refused to vote on removing the limiting statute, which would have allowed the lawsuit to proceed. Clayton was determined that these farmers have a chance to seek justice. She found a strategy mentor in John Conyers, a Black Democrat from Michigan who was the ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee. He advised her to try introducing the removal of the statute of limitations as an amendment on the floor of the Appropriations Committee. When the agriculture appropriations bill came up, Clayton asked the speaker for permission to introduce the amendment, which he granted her. Not wanting Clayton’s amendment to stand in the way of passing their budget, the members of her committee voted for it. “I thank God for Conyers,” Clayton said. “That’s how we got the statute of limitations removed,” she said, enabling the historic lawsuit to proceed. It grew to include more than 22,700 plaintiffs across the South, seeking restitution for decades of discrimination that had led to massive land loss among Black farming families. In 1999, a federal judge approved a settlement agreement for more than $1 billion. Just over 15,500 claimants have received compensation, most getting $50,000, though the disbursal of funds has been far from perfect and many believe the per-farmer sum is not nearly enough to compensate for the damage. For farmers like Warren County’s Arthur Brown—who was part of the second round of Pigford claims—Clayton was a critical voice in Washington. “Eva Clayton spoke for him,” Brown’s son Patrick said. “She went to the local town halls and got information [from farmers] to carry back to Washington to advocate on their behalf.” Pigford II claims were settled in 2010, for an additional $1.25 billion. Clayton said she made a point of meeting with the people in her district at least six times a year, and more often during extended recesses. Hearing directly from those impacted by policies, she said, helped strengthen her arguments and helped her see, as she put it, “where you’re being effective and where there’s possibility.” She also pushed for qualified Black people to lead at least four USDA agencies in North Carolina, including the Farm Service Agency and the Risk Management Agency, said Archie Hart, a special assistant to the North Carolina commissioner of agriculture. For the first time, this opened the door for Black farmers to participate in programs like crop insurance and environmental incentive programs. Between 1978 and 2000, Black farmers in North Carolina had lost 70 percent of their land, Hart said. Clayton’s efforts to connect farmers to federal assistance, he said, “stopped the bleeding.” Clayton was equally dedicated to food access. The welfare reform law that Republicans passed in 1996 made deep cuts to the food stamp program, lowering the maximum benefit, eliminating eligibility for many documented immigrants, and adding work requirements. In the years that followed, Clayton played a key role in the movement to restore food stamps, said Teller. As the senior Democrat on the Ag subcommittee responsible for nutrition programs, she helped author the 2002 Farm Bill which, among other things, expanded food stamp eligibility to documented immigrants in the U.S. and to their children, providing vital assistance to an additional one million legal immigrants working for a better life. Clayton meets with Newt Gingrich, speaker of the House, in the mid 1990s. “FEED the FOLKS” was her campaign to protect the federal school lunch program from drastic cuts proposed by Republicans. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton) Former Rep. Chambliss remembers Clayton sharing the lived experiences of her constituents with the committee. “Because she represented a poor district, she had a lot of anecdotes she could use to back up her position” that the government needed to strengthen its social safety net, he said. As a negotiator, he said, she was very effective: “Just look at the numbers—in the ’02 bill, we bumped up food stamps pretty good.” As Clayton advocated for nutrition assistance, she consistently countered the prevailing stereotypes about Black people, said Hart of North Carolina’s agriculture department. “A lot of other cultures have you down as ‘Black people are just lazy,’” he said. “There are so many prejudices, and she was able to say, ‘Let me explain my culture. People aren’t asking for a handout—they’re asking for their God-given right as citizens.’” Clayton manages to combine intense focus and determination with grandmotherly warmth and a quick sense of humor. During my visits, she called me “darling,” chatted easily about her grandkids and garden, ribbed me for asking too many questions, and once offered me lunch from her fridge so I wouldn’t drive home on an empty stomach. Throughout her career, she was raising her daughter and three sons in rural Warren County. As they grew, she drove them to piano, dance, karate, and basketball practices in nearby towns, Joanne remembers, and when they got sick, she would put washcloths on their foreheads, rub menthol on their chests, and hum them to sleep. Clayton at her house on Lake Gaston, North Carolina. While pursuing a political career, she and her husband raised four children; she now has six grandchildren, too. (Photo credit: Christina Cooke) While Clayton expressed her love in many ways, cooking was not one of them, Joanne continues. “My mother could not cook with a damn,” she said, laughing. (Her father, on the other hand, was excellent in the kitchen.) “My mother burnt toast so much that my father would order burnt toast in restaurants. You know you’re a good husband when you accept defeat: ‘She can’t cook, and not only do I have burnt toast, I want burnt toast. That’s how much I love you, baby.’” Clayton’s feeling of responsibility to her community often drew her away from her family. She was consistently busy with meetings and functions. And sometimes, her drive to better the world came at the expense of her children’s feelings. In 1963, T.T. filed a lawsuit to desegregate the Warren County Schools, and the Claytons sent Joanne to first grade at the all-white Mariam Boyd Elementary. Joanne simply “got through it,” she said, as the other kids subjected her to spitballs and other insults. “I probably should have been more concerned about my kids, but I thought they could handle it,” said Clayton, who sent Theaoseus Jr. and Martin to the same school later. In preparing her kids beforehand, Clayton focused more on the courage required than the harm they might face. Despite the difficulty, Clayton is exceedingly proud to have played a part in integrating the schools and feels the hardship her kids endured was worth it. “Nobody really harmed them,” she said. “They were isolated, I’m sure of that. But they did all right.” Clayton had long said she would serve in Congress for only 10 years. And when that anniversary arrived in 2002, she stepped aside. A year later, she was appointed the assistant director-general of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, based in Rome—fulfilling, in a way, her childhood dream of helping others abroad. At the FAO, she worked on a coalition to cut world hunger in half by 2015, a goal set at the 1996 World Food Summit. The group did not meet its ambitious goal, but, said Clayton, “we organized alliances and partnerships in 24 countries and got people to see the value of working together. That is one thing I still look back on with great pride.” Clayton met with Pope John Paul II to engage the Catholic church in the United Nations effort to halve world hunger, circa 2004. (Photo courtesy of Eva Clayton) Various international organizations, including Rotary International, signed on to the hunger-reduction effort. Clayton met with the pope to get the Catholic church involved, and groups like Bread for the World, a U.S.-based Christian anti-hunger advocacy organization, enlisted as well. Though she is back in Warren County now, Clayton has not given up on the wish to make a dent in food insecurity. “I’ll go to my grave not having fulfilled the goal,” she said, “but I do want to end my existence still trying.” And that is exactly what she is doing, lending her support to a food-security effort closer to home. In 2023, the Green Rural Redevelopment Organization (GRRO), a nonprofit that tackles poverty, food insecurity, and chronic disease in north-central North Carolina, launched a food justice network and named it the Eva Clayton Rural Food Institute to build on her legacy. Clayton is focusing on food in her own life too. T.T. died in 2019, a blow to her heart and spirit. In his absence, she has started teaching herself to cook. “Now I’m wanting to cook the special things,” she said, “like salmon cakes for breakfast.” Clayton, who still speaks publicly on a regular basis, stands in front of the stately red-brick county courthouse in Warrenton in a mid-calf pink and navy dress. The town is celebrating Juneteenth today, and its leaders have requested she speak. “She looks good!” the woman beside me whispers to her friend as Clayton begins. Clayton speaking at the Juneteenth celebration at the Warrenton county courthouse this year. (Photo Credit: Christina Cooke) “This is a day of freedom we are celebrating,” Clayton tells the crowd. “But freedom is really not free.” Citizens are the most vital part of a democracy—more important that elected leaders, she continues. “Citizens elect officials. But we elect them and leave them; we don’t hold them accountable.” Engage with your elected officials, she entreats, pointing her cane in the air. “Freedom requires us collectively to walk forward.” She hands off the mic to a vigorous round of applause and cheers. After mingling and saying goodbye to well-wishers, Clayton heads toward her car parked a few blocks from the courthouse, making her way with care down the uneven sidewalk. On the left, its façade chipped and faded, stands the building that housed T.T.’s law office and his partner’s sandwich shop, where she protested segregation more than 60 years ago. Clayton says she feels grateful to have the desire to still be involved. “At some point, people say, ‘I don’t want to be bothered with certain things,’” she says. “But I do want to be bothered with things. I think that’s a blessing, to live with a purpose.” The post At 91, Eva Clayton Is Still Fighting for Food Justice and Farmers’ Rights appeared first on Civil Eats.

Clayton Goes to Congress

Ultimately, Clayton prevailed, advancing to the national stage and becoming the first Black woman to represent North Carolina in Congress. “The Lord is good,” she told The Virginian-Pilot as she moved ahead of her Republican rival.A Fierce Advocate for Farmers

Protecting and Expanding Federal Food Assistance

Balancing Politics and Motherhood

Combatting Hunger Worldwide—and at Home

A Life of Purpose