Complex Life May Have Evolved Multiple Times

In his laboratory at the University of Poitiers in France, Abderrazak El Albani contemplates the rock glittering in his hands. To the untrained eye, the specimen resembles a piece of golden tortellini embedded in a small slab of black shale. To El Albani, a geochemist, the pasta-shaped component looks like the remains of a complex life-form that became fossilized when the sparkling mineral pyrite replaced the organism’s tissues after death. But the rock is hundreds of millions of years older than the oldest accepted fossils of advanced multicellular life. The question of whether it is a paradigm-shifting fossil or merely an ordinary lump of fool’s gold has consumed El Albani for the past 17 years.In January 2008 El Albani, a talkative French Moroccan, was picking over an exposed scrape of black shale outside the town of Franceville in Gabon. Lying under rolling hills of tropical savanna, cut in places by muddy rivers lined by jungle, the rock layers of the Francevillian Basin are up to 2.14 billion years old. The strata are laced with enough manganese to support a massive mining industry. But El Albani was there pursuing riches of a different kind.Most sedimentary rocks of that age are thoroughly “cooked,” transformed beyond recognition by the brutal heat and pressure of deep burial and deeper time. Limestone is converted to marble, sandstone to quartzite. But through an accident of geology, the Francevillian rocks were protected, and their sediments have maintained something of their original shape, crystal structure and mineral composition. As a result, they offer a rare window into a stretch of time when, according to paleontologists, oxygen was in much shorter supply and Earth’s environments would have been hostile to multicellular organisms like the ones that surround us today.On supporting science journalismIf you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.El Albani had been invited out by the Gabonese government to conduct a geological survey of the ancient sediments. He spent half a day wandering the five-meter-deep layer of the quarry, peeling apart slabs of shale as if opening pages of a book. The rocks were filled with gleaming bits of pyrite that occurred in a variety of bizarre shapes. El Albani couldn’t immediately explain their appearance by any common sedimentary process. Baffled, he took a few samples with him when he returned to Poitiers. Two months later he scraped together funding to head back to the Francevillian quarry. This time he went home with more than 200 kilograms of specimens in his luggage.In 2010 El Albani and a team of his colleagues made a bombshell claim based on those finds: the strangely shaped specimens they’d recovered in Franceville were fossils of complex life-forms—organisms made up of multiple, specialized cells—that lived in colonies long before any such thing is supposed to have existed. If the scientists were right, the traditional account of life’s beginning, which holds that complex life originated once around 1.6 billion years ago, is wrong. And not only did complex multicellular life appear earlier than previously thought, but it might have done so multiple times, sprouting seedlings that were wiped away by a volatile Earth eons before our lineage took root. El Albani and his colleagues have pursued this argument ever since.Rocks from the Francevillian Basin in Gabon are filled with gleaming shapes that have been interpreted as fossils of complex life-forms from more than two billion years ago.Abderrazak El Albani/University of PoitiersThe potential implications of their claims are immense—they stand to rewrite nearly the entire history of life on Earth. They’re also incredibly controversial. Almost immediately, prominent researchers argued that El Albani’s specimens are actually concretions of natural pyrite that only look like fossils. Mentions of the Francevillian rocks in the scientific literature tend to be accompanied by words such as “uncertain” and “questionable.”Yet even as most experts regard the Francevillian specimens with a skeptical eye, a slew of recent discoveries from other teams have challenged older, simpler stories about the origin of life. Together with these new finds, the sparkling rock El Albani held in his hands has raised some very tricky questions. What conditions did complex life need to emerge? How can we recognize remains of life from deep time when organisms then would have been entirely different from those that we know? And where do the burdens of proof lie for establishing that complex life arose far earlier than previously thought—and more than just once?By most accounts, life on Earth first emerged around four billion years ago. In the beginning, the oxygen that sustains most species today had yet to suffuse the world’s atmosphere and oceans. Single-celled microbes reigned supreme. In the anoxic waters, bacteria spread and fed on minerals around hydrothermal vents. Then, maybe 2.5 billion years ago, so-called cyanobacteria that gathered in mats and gave rise to great stone domes called stromatolites began feeding themselves using the power of the sun. In doing so, they kick-started a slow transformation of the planet, pumping Earth’s seas and atmosphere full of oxygen as a by-product of their feeding.That transformation would eventually devastate the first, oxygen-averse microbial residents of Earth. But amid a gathering oxygen apocalypse, something new appeared. Roughly two billion years ago a symbiotic union between two groups of single-celled organisms—one of which was able to process oxygen—gave rise to the earliest eukaryotes: larger cells with a membrane-bound nucleus, distinctive biochemistry and an aptitude for sticking together. Somewhere in the vast sweep of time between then and now, in something of a glorious accident, those eukaryotes began banding together in specialized ways, forming intricate and increasingly complex multicellular organisms: algae, seaweeds, plants, fungi and animals.Scholars have long endeavored to understand when that transition from the single-celled to the multicellular happened. By the mid-19th century researchers noticed that the fossil record got considerably livelier at a certain point, which we now know was around 540 million years ago. During this period, called the Cambrian, multicellular eukaryotes seemed to explode in diversity out of nowhere. Suddenly the seas were filled with trilobites, meter-long predatory arthropods, and even the earliest forerunners of vertebrates, the backboned lineage of animals to which we humans belong.But it wasn’t long before scientists began finding older hints of multicellular organisms, suggesting that complex life proliferated before the Cambrian. In 1868 a geologist proposed that tiny, disk-shaped objects from sediments more than 500 million years old in Newfoundland were fossils—only for other researchers to dismiss them as inorganic concretions. Similarly ancient fossils from elsewhere in the world turned up over the first half of the 20th century. The most famous of them—discovered in Australia’s Ediacara Hills by geologist Reginald Claude Sprigg, who took them to be jellyfish—helped to push the dawn of complex life back to least 600 million years ago, into what came to be called the Ediacaran period.Still, a gap of more than a billion years separates the earliest known eukaryotes and their great flowering in the Ediacaran. The contrast between the apparent evolutionary stasis of the bulk of this period and the eventful periods before and after it is so stark that researchers variously refer to it as “the dullest time in Earth’s history” and the “boring billion.” Why didn’t many-celled eukaryotes start diversifying earlier, wonders Susannah Porter, a paleontologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara? Why didn’t they explode until the Ediacaran?Researchers have historically blamed environmental conditions on ancient Earth for the delay. The dawn of the Ediacaran, they note, coincided with a noticeable shift in global conditions 635 million years ago. In the wake of a world-spanning glacial event—the so-called Snowball Earth period, when great sheets of ice scraped the continents and covered the seas—the available nutrients in the oceans shifted amid a surge in levels of available oxygen. The friendlier water chemistry and more abundant oxygen provided new opportunities for eukaryotic organisms that could exploit them. They diversified quickly and dramatically, first into the stationary animals of the Ediacaran and eventually into the more active grazers and hunters of the Cambrian. It’s a commonly cited explanation for the timing of life’s big bang, one that the field tends to accept, Porter says. And it may well be correct. But if you asked El Albani, he’d say it’s not the whole story—far from it.As a kid growing up in Marrakech, El Albani wasn’t interested in geology; football and medicine held more appeal. He drifted into the field when he was 20 largely because it let him spend time outside. He then fell in love with it in part because like his father, a police officer, he enjoys a good investigation, working out what happened in some distant event by laying out multiple lines of evidence.In the case of the ancient Gabon “fossils,” the first line of evidence involves the unusual geology of the Francevillian formation. Unlike most sedimentary rocks laid down two billion years ago—fated for deep burial and transformative heat and pressure—the Francevillian strata sit within a bowl of much tougher rock, which prevented them from being cooked. The result: shales able to preserve both biological forms and something close to the primary chemicals and minerals present in the marine sediments. “It gives us the possibility of actually reconstructing this environment that existed in the past, at a scale that we don’t see anywhere around this time,” says Ernest Chi Fru, a biogeochemist at Cardiff University in Wales, who has worked with El Albani on the Francevillian material. If you were searching for fossils of relatively large, soft-bodied multicellular organisms from this period, the Francevillian is exactly the kind of place you’d look in.“I don’t know what we need to show to prove, to convince.” —Abderrazak El Albani University of PoitiersEl Albani’s team has recovered quite a few such specimens. Three narrow rooms in the geology building at the University of Poitiers house the Francevillian collection. More than 6,000 pieces—all of them collected from the same five-meter scrape of Gabonese shale—sprawl over wood shelves and tables and glass display cabinets, the black slabs arranged in puzzle-piece configurations under white walls. El Albani is eager to show them off. He plucks out rock after rock, no sooner highlighting one when he’s distracted by another. Here are the ripplelike remnants of bacterial mats. There are the specimens encrusted with pyrite: the common, tortellinilike “lobate” forms that made the cover of the journal Nature in 2010, “tubate” shapes that resemble stethoscopes and spoons, and other forms similar to strings of pearls several centimeters long. There are strange, wormlike tracks that the team has suggested could be traces of movement. There are nonpyritized remains, too: sand-dollar-like circles ranging from one to several centimeters across imprinted on the shales.“Et voilà,” El Albani says, tapping one specimen and then another. “You see? This is totally different.” The sheer variety of forms is why he’s always surprised that people could look at them and assume they aren’t in fact fossils. Nevertheless, his lab has been exploring ways to attempt to prove their identity.One approach El Albani’s lab has taken recently is looking into the chemistry of the specimens. Eukaryotic organisms tend to take up lighter forms, or isotopes, of elements such as zinc rather than heavy ones. When examining the sand-dollar-shaped impressions in 2023, the team found that the zinc isotopes in them were mostly lighter forms, suggesting the impressions could have been made by eukaryotes. (An independent team ran a similar study of one of the pyritized specimens and reached a similar conclusion.)Earlier this year El Albani’s Ph.D. student Anna El Khoury reported another potential chemical signal for life in the contested rocks. Organisms in areas thick with arsenic sometimes absorb the poisonous chemical instead of necessary nutrients such as phosphate. Whereas confirmed mineral concretions from the Francevillian show a random distribution of arsenic in the rock, the possibly organic specimens El Khoury looked at showed dramatic concentrations of the toxin only in certain parts of the specimens, as would be expected if an organism’s cells were working to isolate the absorbed substance from more vulnerable tissues.What El Albani and his colleagues find most telling, however, are the environmental conditions that are now known to have prevailed when the putative fossils formed. The sediments that make up the Francevillian strata appear to have been deposited in something like an inland sea. The rocks show signals of dramatic underwater volcanism and hydrothermal vent activity from long before the first fossil specimens appear, which left the basin awash in nutrients such as phosphorus and zinc that are crucial for the chemical processes that power living cells.Chemical analyses of the Francevillian specimens suggest that they are the remains of eukaryotic organisms.Abderrazak El Albani/University of PoitiersWhat is more, the Francevillian samples, like the Ediacaran fossils, are from a time after a major period of ice ages: the Huronian glaciation event, wherein a surge in oxygen levels and a reduction in the greenhouse effect 2.4 billion to 2.1 billion years ago unleashed massive walls of ice from the poles. According to some analyses, that spike in oxygen levels might have hit a peak close to that in the Ediacaran before eventually falling again. In other words, the same environmental conditions that are thought to have allowed complex life to flower during the Ediacaran also occurred far earlier and could have set the stage for the emergence of Francevillian life-forms.Talk with the people in El Albani’s lab about the Francevillian, and they’ll paint you a picture of an alien world. Ancient shorelines run under the brooding gaze of distant mountains, silent but for the wind and the waves. Thick mats of bacteria stretch across the underwater sediments. Swim down 20 meters offshore, through waters thick with nutrients and heavy metals such as arsenic, and you might see colonies of spherical and tube-shaped organisms clustered amid the mats. In the oxygen-rich water column, soft-bodied organisms drift like jellyfish, sinking now and then into the mire. Below the silt, unseen movers leave spiraling mucus trails in the ooze.What were these strange forms of life? Not plants or animals as we understand them. Based on the sizes, shapes and geochemical signatures of the putative fossils, El Albani thinks they might belong to a lineage of colonial eukaryotes—perhaps something resembling a slime mold—that independently developed the complex multicellular processes needed to survive at large sizes. These colonial organisms would have been comparatively early offshoots of the eukaryotic tree, making them an entirely independent flowering of complex multicellular life from the Ediacaran bloom that took place more than a billion years later.The Francevillian organisms flourished for a time, but they did not last. After a few millennia, underwater volcanism started up again, and oxygen levels crashed. A billion years would pass before another global icebox phase and another oxygen spike gave multicellular eukaryotes another shot at emergence.This story flies in the face of decades of thinking about how complex life arose. El Albani’s team argues that rather than long epochs of stillness and stasis, rather than the rise of complex life being an extraordinary and long-brewing accident in Earth’s long history, multicellular organisms might not have been a singular innovation. “It seems to me that [the Francevillian material] is showing that complex life might have evolved twice in history,” Chi Fru says. And if ancient complex life can emerge so quickly when conditions are right, who knows where else in Earth’s rocks—or another planet’s—signs of another blossoming might turn up next? “If,” of course, being the operative word.Skeptics of El Albani’s Francevillian “fossils”—and there are many—have tended to gather around similar sticking points, says Leigh Anne Riedman, a paleontologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. For one thing, the bizarre shapes of the rocks show a lot more variety than tends to be seen in accepted early complex multicellular forms, and with their amorphous, asymmetrical features, they do not scan easily as organisms.The pyritized nature of the rocks may also be cause for concern. Colonies of bacteria living in oxygen-poor environments often deposit pyrite as a by-product. Although such colonies can grow a sparkling rind around biological material, the mineral concretions can also develop on their own, developing lifelike appearances without any biological process. Critics of the Francevillian hypothesis point to a well-known phenomenon of pyrite “suns” or “flowers,” superficially fossil-like accumulations of minerals that occasionally turn up in sediments rich in actual fossils. Shuhai Xiao, a paleontologist at Virginia Tech specializing in the Precambrian era, notes that the Francevillian material resembles similar-looking inorganic structures from Michigan that date to 1.1 billion years ago.If ancient complex life can emerge so quickly when conditions are right, who knows where else signs of another blossoming might turn up next?Even scientists who are more amenable to the idea that El Albani’s specimens are fossils tend to conclude that the pyritized specimens are probably just the remains of bacterial mats, not complex life-forms. An independent radiation of colonial eukaryotes at such an age? That’s a hard sell. “I have no problem with there being oxygen oases and there being certain groups that proliferated during those periods,” Riedman says. But the idea that they would have proliferated to that size—a jump in scale that another researcher equated to that between a human and an aircraft carrier—without any similar fossils turning up elsewhere gives her pause. “It just seems a little bit of a stretch.”Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, however. In the case of the Proterozoic fossil record, the lack of other candidate fossils of complex life as old as those from the Francevillian may reflect a lack of effort in searching for them. That is, the apparent quiet of the deep past may be an illusion—less the “boring billion” than, as Porter puts it, the “barely sampled billion.”The dullness of vast chunks of the Proterozoic has been a self-fulfilling prophecy, Riedman says. After all, who wants to devote time and scarce funding to a period when nothing much is supposed to have happened? “That name, man,” Riedman says of the boring billion. “We’ve got to kill it. Kill it with fire.”Recent findings may help reform the Proterozoic’s cursed reputation—and cast the Francevillian rocks in a more plausible light. Just last year Lanyun Miao of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and her colleagues announced that they had discovered the oldest unequivocal multicellular eukaryotes in 1.6-billion-year-old rocks from northern China. The fossils preserve small, threadlike organisms. They’re a far cry from the much larger, more elaborate forms associated with complex multicellularity. But they show that these simpler kinds of multicellular life existed some 500 million years earlier than previously hypothesized.There’s good reason to think the roots of the eukaryote family tree could run considerably deeper than that. Analyses of genome sequences and fossils have hinted that the earliest common ancestor of all living eukaryotes may have appeared as long as 1.9 billion years ago.Critics argue that the forms evident in the Francevillian rocks are merely mineral concretions, not fossils of complex eukaryotic organisms.Abderrazak El Albani/University of PoitiersAnd complex multicellularity itself may develop surprisingly fast. In a fascinating experiment published a few years ago, a team at the Georgia Institute of Technology was able to get single-celled eukaryotes—in this case, yeasts—to chain together in multicellular forms visible to the naked eye in just two years. These findings, along with the growing fossil record, suggest to some researchers that multicellular eukaryotes have a deeper history than is generally recognized.But recognizing early life in the rock is notoriously tricky. Brooke Johnson, a paleontologist at the University of Liège in Belgium, has visited Ediacaran outcrops in the U.K. with his colleagues and sometimes struggled to spot the specific fossils he knows are there.Assessing unfamiliar structures is even more fraught. Researchers constantly second-guess themselves for fear of overinterpreting any given shape or shadow in the stone. The specter of crankhood—of being the kind of researcher who drives their work off a cliff by refusing to be proved wrong—hangs over everybody. “It’s very easy to get yourself tricked into thinking that you can see something that isn’t there, because you’re used to seeing a particular pattern,” Johnson says.One spring morning in 2023, while working through hundreds of samples of rock more than one billion years old from drill cores from Australia, Johnson knocked over one of the pieces. The rock rolled into a strip of sunlight cutting through the blinds. Johnson abruptly noticed structures picked out by the low-angle light like tiny, quilted chains across the surface of the stone. A careful reexamination of many of the drill cores—rocks many previous geologists had handled without comment—showed the structures were common across the samples.Johnson speaks cautiously about the structures and has yet to publish his findings on them formally. But he thinks they might be some type of colony-living eukaryote of a size significantly larger than the microscopic examples known from elsewhere in the early fossil record.The fact that Johnson noticed the structures in the drill core samples only by chance has shaken his initial skepticism of El Albani’s work. “Something like the Francevillian stuff, people might have found it already in other rocks and just not seen it,” he says. “It just might be because they haven’t looked at it in the right way.”The sheer vanity of forms is why El Albani is surprised that people could look at them and assume they aren’t fossils.Dealing with material like the Francevillian requires trying to understand a time when Earth looked virtually nothing like the world we know now, Porter says. Much of the history of multicellular life occurred across an abyss of time on what was effectively an alien planet, with environmental conditions that were remarkably different from those of the past 600 million years. These conditions affected life in ways that are still only dimly understood. And the further back in time one goes, the more likely it is that any fossils will be difficult to recognize, to say nothing of categorize.The temptation for the field to dismiss “fossil-ish” forms as mineral concretions or the product of some other nonbiological process rather than a biogenic one therefore exerts a nearly gravitational pull. “I would imagine they’re probably frustrated [and thinking], ‘Why isn’t everybody already excited about this and coming along with us?’” Riedman says of El Albani and his colleagues. “And we’re just like, ‘We’re stuck on step one, man. We haven’t gotten past the biogenic part.’”“I don’t know what we need to show to prove, to convince,” El Albani says, his expression hangdog. He’s sitting in his office below a poster of the cover of a June 2024 issue of Science in which he and his team published their discovery of a remarkable trilobite fossil. “There’s no trouble with trilobites,” he remarks wistfully. El Albani is not a bomb thrower by nature and is not in a rush to name names. But a visible exasperation creeps in when he discusses the Gabonese specimens, along with a tendency to simultaneously pick at and try to dismiss the wound.At the end of the day, it is a question not really of belief but of arguments, El Albani says. If his critics believe the Gabonese specimens are concretions, they need to try to prove that rather than simply asserting it. If they disagree that the rocks contain fossils of eukaryotes, nothing is stopping them from subjecting the specimens to their own analyses. So far he feels that nobody has published any research that takes their conclusions apart point by point and reckons with all the strands of evidence they’ve marshaled. “If I give my opinion that your iPhone is Samsung,” he says, pulling a phone across the desk, “I should explain why!”Porter, the U.C.S.B. paleontologist, agrees. She’s not convinced by the team’s arguments for what the Francevillian samples represent—an independent lineage of colonial multicellular organisms, swiftly flowering, swiftly snuffed out. But the idea that they’re all just mineral concretions has never satisfied her. If they’re concretions, that’s something researchers need to affirmatively show, she says. Doing so, after all, would add to the field’s knowledge about how pseudofossils form in a way that simply writing them off does not. “We don’t want to discourage people from publishing these weird structures that are difficult to understand,” Porter says.“It’s fine if they’re wrong,” Porter says of El Albani and his colleagues. Everyone is offering competing hypotheses, which are always subject to new evidence from the fossil record. In the end, “we’ll probably all be somewhat wrong about our interpretation, actually.”Seventeen years after El Albani first stopped to examine a glinting blob in the Gabonese shale, his lab shows no signs of slowing down. There are always more specimens to publish, avenues of research to pursue, dissertations to finish. Members of the group are working on closer comparisons between the different environments preserved in the Francevillian quarry and the Cambrian deposits, between the chemistry of the Gabonese specimens and fossils from the Ediacaran and the Burgess Shale.They’re also digging further into the question of how, precisely, chemistry can definitively distinguish between biological and nonbiological origins for a given specimen. Findings from research like theirs could eventually be used to evaluate rock samples from other planets. In 2020 a team of researchers reported that the NASA Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity had photographed millimeter-size, sticklike structures in an ancient lake bed that resembled fossils left by miniature tunnelers on Earth. To date, it’s been impossible to disprove nonbiological explanations for their presence. But if a lab could develop a reliable conceptual model for chemically distinguishing between signs of life and nonlife, “you could apply this on Mars or another planet based on the sediment,” El Albani says.Every year El Albani and his team make the trip to Gabon to work the scrape of black stone that reoriented his life. There they comb the flaking shales, prying apart slabs, alert to the glimmer of pyrite or the soft, subtle impression of a circular form stamped in the petrified silt. Sometimes El Albani live-streams the expeditions to French schoolchildren, explaining to them how the cellular revolution that gave rise to them lies far back in the mists of prehistory. Sometimes he bends down to examine a glittering form in the rock. It’s probably something. The question, as always, is what.

Controversial evidence hints that complex life might have emerged hundreds of millions of years earlier than previously thought—and possibly more than once

In his laboratory at the University of Poitiers in France, Abderrazak El Albani contemplates the rock glittering in his hands. To the untrained eye, the specimen resembles a piece of golden tortellini embedded in a small slab of black shale. To El Albani, a geochemist, the pasta-shaped component looks like the remains of a complex life-form that became fossilized when the sparkling mineral pyrite replaced the organism’s tissues after death. But the rock is hundreds of millions of years older than the oldest accepted fossils of advanced multicellular life. The question of whether it is a paradigm-shifting fossil or merely an ordinary lump of fool’s gold has consumed El Albani for the past 17 years.

In January 2008 El Albani, a talkative French Moroccan, was picking over an exposed scrape of black shale outside the town of Franceville in Gabon. Lying under rolling hills of tropical savanna, cut in places by muddy rivers lined by jungle, the rock layers of the Francevillian Basin are up to 2.14 billion years old. The strata are laced with enough manganese to support a massive mining industry. But El Albani was there pursuing riches of a different kind.

Most sedimentary rocks of that age are thoroughly “cooked,” transformed beyond recognition by the brutal heat and pressure of deep burial and deeper time. Limestone is converted to marble, sandstone to quartzite. But through an accident of geology, the Francevillian rocks were protected, and their sediments have maintained something of their original shape, crystal structure and mineral composition. As a result, they offer a rare window into a stretch of time when, according to paleontologists, oxygen was in much shorter supply and Earth’s environments would have been hostile to multicellular organisms like the ones that surround us today.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

El Albani had been invited out by the Gabonese government to conduct a geological survey of the ancient sediments. He spent half a day wandering the five-meter-deep layer of the quarry, peeling apart slabs of shale as if opening pages of a book. The rocks were filled with gleaming bits of pyrite that occurred in a variety of bizarre shapes. El Albani couldn’t immediately explain their appearance by any common sedimentary process. Baffled, he took a few samples with him when he returned to Poitiers. Two months later he scraped together funding to head back to the Francevillian quarry. This time he went home with more than 200 kilograms of specimens in his luggage.

In 2010 El Albani and a team of his colleagues made a bombshell claim based on those finds: the strangely shaped specimens they’d recovered in Franceville were fossils of complex life-forms—organisms made up of multiple, specialized cells—that lived in colonies long before any such thing is supposed to have existed. If the scientists were right, the traditional account of life’s beginning, which holds that complex life originated once around 1.6 billion years ago, is wrong. And not only did complex multicellular life appear earlier than previously thought, but it might have done so multiple times, sprouting seedlings that were wiped away by a volatile Earth eons before our lineage took root. El Albani and his colleagues have pursued this argument ever since.

Rocks from the Francevillian Basin in Gabon are filled with gleaming shapes that have been interpreted as fossils of complex life-forms from more than two billion years ago.

Abderrazak El Albani/University of Poitiers

The potential implications of their claims are immense—they stand to rewrite nearly the entire history of life on Earth. They’re also incredibly controversial. Almost immediately, prominent researchers argued that El Albani’s specimens are actually concretions of natural pyrite that only look like fossils. Mentions of the Francevillian rocks in the scientific literature tend to be accompanied by words such as “uncertain” and “questionable.”

Yet even as most experts regard the Francevillian specimens with a skeptical eye, a slew of recent discoveries from other teams have challenged older, simpler stories about the origin of life. Together with these new finds, the sparkling rock El Albani held in his hands has raised some very tricky questions. What conditions did complex life need to emerge? How can we recognize remains of life from deep time when organisms then would have been entirely different from those that we know? And where do the burdens of proof lie for establishing that complex life arose far earlier than previously thought—and more than just once?

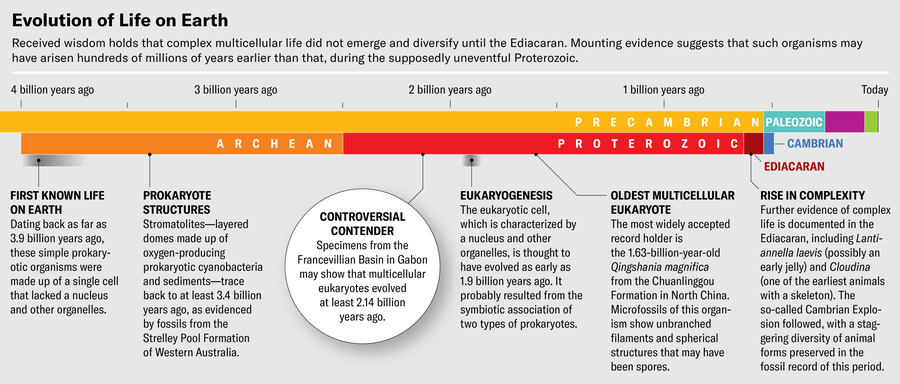

By most accounts, life on Earth first emerged around four billion years ago. In the beginning, the oxygen that sustains most species today had yet to suffuse the world’s atmosphere and oceans. Single-celled microbes reigned supreme. In the anoxic waters, bacteria spread and fed on minerals around hydrothermal vents. Then, maybe 2.5 billion years ago, so-called cyanobacteria that gathered in mats and gave rise to great stone domes called stromatolites began feeding themselves using the power of the sun. In doing so, they kick-started a slow transformation of the planet, pumping Earth’s seas and atmosphere full of oxygen as a by-product of their feeding.

That transformation would eventually devastate the first, oxygen-averse microbial residents of Earth. But amid a gathering oxygen apocalypse, something new appeared. Roughly two billion years ago a symbiotic union between two groups of single-celled organisms—one of which was able to process oxygen—gave rise to the earliest eukaryotes: larger cells with a membrane-bound nucleus, distinctive biochemistry and an aptitude for sticking together. Somewhere in the vast sweep of time between then and now, in something of a glorious accident, those eukaryotes began banding together in specialized ways, forming intricate and increasingly complex multicellular organisms: algae, seaweeds, plants, fungi and animals.

Scholars have long endeavored to understand when that transition from the single-celled to the multicellular happened. By the mid-19th century researchers noticed that the fossil record got considerably livelier at a certain point, which we now know was around 540 million years ago. During this period, called the Cambrian, multicellular eukaryotes seemed to explode in diversity out of nowhere. Suddenly the seas were filled with trilobites, meter-long predatory arthropods, and even the earliest forerunners of vertebrates, the backboned lineage of animals to which we humans belong.

But it wasn’t long before scientists began finding older hints of multicellular organisms, suggesting that complex life proliferated before the Cambrian. In 1868 a geologist proposed that tiny, disk-shaped objects from sediments more than 500 million years old in Newfoundland were fossils—only for other researchers to dismiss them as inorganic concretions. Similarly ancient fossils from elsewhere in the world turned up over the first half of the 20th century. The most famous of them—discovered in Australia’s Ediacara Hills by geologist Reginald Claude Sprigg, who took them to be jellyfish—helped to push the dawn of complex life back to least 600 million years ago, into what came to be called the Ediacaran period.

Still, a gap of more than a billion years separates the earliest known eukaryotes and their great flowering in the Ediacaran. The contrast between the apparent evolutionary stasis of the bulk of this period and the eventful periods before and after it is so stark that researchers variously refer to it as “the dullest time in Earth’s history” and the “boring billion.” Why didn’t many-celled eukaryotes start diversifying earlier, wonders Susannah Porter, a paleontologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara? Why didn’t they explode until the Ediacaran?

Researchers have historically blamed environmental conditions on ancient Earth for the delay. The dawn of the Ediacaran, they note, coincided with a noticeable shift in global conditions 635 million years ago. In the wake of a world-spanning glacial event—the so-called Snowball Earth period, when great sheets of ice scraped the continents and covered the seas—the available nutrients in the oceans shifted amid a surge in levels of available oxygen. The friendlier water chemistry and more abundant oxygen provided new opportunities for eukaryotic organisms that could exploit them. They diversified quickly and dramatically, first into the stationary animals of the Ediacaran and eventually into the more active grazers and hunters of the Cambrian. It’s a commonly cited explanation for the timing of life’s big bang, one that the field tends to accept, Porter says. And it may well be correct. But if you asked El Albani, he’d say it’s not the whole story—far from it.

As a kid growing up in Marrakech, El Albani wasn’t interested in geology; football and medicine held more appeal. He drifted into the field when he was 20 largely because it let him spend time outside. He then fell in love with it in part because like his father, a police officer, he enjoys a good investigation, working out what happened in some distant event by laying out multiple lines of evidence.

In the case of the ancient Gabon “fossils,” the first line of evidence involves the unusual geology of the Francevillian formation. Unlike most sedimentary rocks laid down two billion years ago—fated for deep burial and transformative heat and pressure—the Francevillian strata sit within a bowl of much tougher rock, which prevented them from being cooked. The result: shales able to preserve both biological forms and something close to the primary chemicals and minerals present in the marine sediments. “It gives us the possibility of actually reconstructing this environment that existed in the past, at a scale that we don’t see anywhere around this time,” says Ernest Chi Fru, a biogeochemist at Cardiff University in Wales, who has worked with El Albani on the Francevillian material. If you were searching for fossils of relatively large, soft-bodied multicellular organisms from this period, the Francevillian is exactly the kind of place you’d look in.

“I don’t know what we need to show to prove, to convince.” —Abderrazak El Albani University of Poitiers

El Albani’s team has recovered quite a few such specimens. Three narrow rooms in the geology building at the University of Poitiers house the Francevillian collection. More than 6,000 pieces—all of them collected from the same five-meter scrape of Gabonese shale—sprawl over wood shelves and tables and glass display cabinets, the black slabs arranged in puzzle-piece configurations under white walls. El Albani is eager to show them off. He plucks out rock after rock, no sooner highlighting one when he’s distracted by another. Here are the ripplelike remnants of bacterial mats. There are the specimens encrusted with pyrite: the common, tortellinilike “lobate” forms that made the cover of the journal Nature in 2010, “tubate” shapes that resemble stethoscopes and spoons, and other forms similar to strings of pearls several centimeters long. There are strange, wormlike tracks that the team has suggested could be traces of movement. There are nonpyritized remains, too: sand-dollar-like circles ranging from one to several centimeters across imprinted on the shales.

“Et voilà,” El Albani says, tapping one specimen and then another. “You see? This is totally different.” The sheer variety of forms is why he’s always surprised that people could look at them and assume they aren’t in fact fossils. Nevertheless, his lab has been exploring ways to attempt to prove their identity.

One approach El Albani’s lab has taken recently is looking into the chemistry of the specimens. Eukaryotic organisms tend to take up lighter forms, or isotopes, of elements such as zinc rather than heavy ones. When examining the sand-dollar-shaped impressions in 2023, the team found that the zinc isotopes in them were mostly lighter forms, suggesting the impressions could have been made by eukaryotes. (An independent team ran a similar study of one of the pyritized specimens and reached a similar conclusion.)

Earlier this year El Albani’s Ph.D. student Anna El Khoury reported another potential chemical signal for life in the contested rocks. Organisms in areas thick with arsenic sometimes absorb the poisonous chemical instead of necessary nutrients such as phosphate. Whereas confirmed mineral concretions from the Francevillian show a random distribution of arsenic in the rock, the possibly organic specimens El Khoury looked at showed dramatic concentrations of the toxin only in certain parts of the specimens, as would be expected if an organism’s cells were working to isolate the absorbed substance from more vulnerable tissues.

What El Albani and his colleagues find most telling, however, are the environmental conditions that are now known to have prevailed when the putative fossils formed. The sediments that make up the Francevillian strata appear to have been deposited in something like an inland sea. The rocks show signals of dramatic underwater volcanism and hydrothermal vent activity from long before the first fossil specimens appear, which left the basin awash in nutrients such as phosphorus and zinc that are crucial for the chemical processes that power living cells.

Chemical analyses of the Francevillian specimens suggest that they are the remains of eukaryotic organisms.

Abderrazak El Albani/University of Poitiers

What is more, the Francevillian samples, like the Ediacaran fossils, are from a time after a major period of ice ages: the Huronian glaciation event, wherein a surge in oxygen levels and a reduction in the greenhouse effect 2.4 billion to 2.1 billion years ago unleashed massive walls of ice from the poles. According to some analyses, that spike in oxygen levels might have hit a peak close to that in the Ediacaran before eventually falling again. In other words, the same environmental conditions that are thought to have allowed complex life to flower during the Ediacaran also occurred far earlier and could have set the stage for the emergence of Francevillian life-forms.

Talk with the people in El Albani’s lab about the Francevillian, and they’ll paint you a picture of an alien world. Ancient shorelines run under the brooding gaze of distant mountains, silent but for the wind and the waves. Thick mats of bacteria stretch across the underwater sediments. Swim down 20 meters offshore, through waters thick with nutrients and heavy metals such as arsenic, and you might see colonies of spherical and tube-shaped organisms clustered amid the mats. In the oxygen-rich water column, soft-bodied organisms drift like jellyfish, sinking now and then into the mire. Below the silt, unseen movers leave spiraling mucus trails in the ooze.

What were these strange forms of life? Not plants or animals as we understand them. Based on the sizes, shapes and geochemical signatures of the putative fossils, El Albani thinks they might belong to a lineage of colonial eukaryotes—perhaps something resembling a slime mold—that independently developed the complex multicellular processes needed to survive at large sizes. These colonial organisms would have been comparatively early offshoots of the eukaryotic tree, making them an entirely independent flowering of complex multicellular life from the Ediacaran bloom that took place more than a billion years later.

The Francevillian organisms flourished for a time, but they did not last. After a few millennia, underwater volcanism started up again, and oxygen levels crashed. A billion years would pass before another global icebox phase and another oxygen spike gave multicellular eukaryotes another shot at emergence.

This story flies in the face of decades of thinking about how complex life arose. El Albani’s team argues that rather than long epochs of stillness and stasis, rather than the rise of complex life being an extraordinary and long-brewing accident in Earth’s long history, multicellular organisms might not have been a singular innovation. “It seems to me that [the Francevillian material] is showing that complex life might have evolved twice in history,” Chi Fru says. And if ancient complex life can emerge so quickly when conditions are right, who knows where else in Earth’s rocks—or another planet’s—signs of another blossoming might turn up next? “If,” of course, being the operative word.

Skeptics of El Albani’s Francevillian “fossils”—and there are many—have tended to gather around similar sticking points, says Leigh Anne Riedman, a paleontologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. For one thing, the bizarre shapes of the rocks show a lot more variety than tends to be seen in accepted early complex multicellular forms, and with their amorphous, asymmetrical features, they do not scan easily as organisms.

The pyritized nature of the rocks may also be cause for concern. Colonies of bacteria living in oxygen-poor environments often deposit pyrite as a by-product. Although such colonies can grow a sparkling rind around biological material, the mineral concretions can also develop on their own, developing lifelike appearances without any biological process. Critics of the Francevillian hypothesis point to a well-known phenomenon of pyrite “suns” or “flowers,” superficially fossil-like accumulations of minerals that occasionally turn up in sediments rich in actual fossils. Shuhai Xiao, a paleontologist at Virginia Tech specializing in the Precambrian era, notes that the Francevillian material resembles similar-looking inorganic structures from Michigan that date to 1.1 billion years ago.

If ancient complex life can emerge so quickly when conditions are right, who knows where else signs of another blossoming might turn up next?

Even scientists who are more amenable to the idea that El Albani’s specimens are fossils tend to conclude that the pyritized specimens are probably just the remains of bacterial mats, not complex life-forms. An independent radiation of colonial eukaryotes at such an age? That’s a hard sell. “I have no problem with there being oxygen oases and there being certain groups that proliferated during those periods,” Riedman says. But the idea that they would have proliferated to that size—a jump in scale that another researcher equated to that between a human and an aircraft carrier—without any similar fossils turning up elsewhere gives her pause. “It just seems a little bit of a stretch.”

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, however. In the case of the Proterozoic fossil record, the lack of other candidate fossils of complex life as old as those from the Francevillian may reflect a lack of effort in searching for them. That is, the apparent quiet of the deep past may be an illusion—less the “boring billion” than, as Porter puts it, the “barely sampled billion.”

The dullness of vast chunks of the Proterozoic has been a self-fulfilling prophecy, Riedman says. After all, who wants to devote time and scarce funding to a period when nothing much is supposed to have happened? “That name, man,” Riedman says of the boring billion. “We’ve got to kill it. Kill it with fire.”

Recent findings may help reform the Proterozoic’s cursed reputation—and cast the Francevillian rocks in a more plausible light. Just last year Lanyun Miao of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and her colleagues announced that they had discovered the oldest unequivocal multicellular eukaryotes in 1.6-billion-year-old rocks from northern China. The fossils preserve small, threadlike organisms. They’re a far cry from the much larger, more elaborate forms associated with complex multicellularity. But they show that these simpler kinds of multicellular life existed some 500 million years earlier than previously hypothesized.

There’s good reason to think the roots of the eukaryote family tree could run considerably deeper than that. Analyses of genome sequences and fossils have hinted that the earliest common ancestor of all living eukaryotes may have appeared as long as 1.9 billion years ago.

Critics argue that the forms evident in the Francevillian rocks are merely mineral concretions, not fossils of complex eukaryotic organisms.

Abderrazak El Albani/University of Poitiers

And complex multicellularity itself may develop surprisingly fast. In a fascinating experiment published a few years ago, a team at the Georgia Institute of Technology was able to get single-celled eukaryotes—in this case, yeasts—to chain together in multicellular forms visible to the naked eye in just two years. These findings, along with the growing fossil record, suggest to some researchers that multicellular eukaryotes have a deeper history than is generally recognized.

But recognizing early life in the rock is notoriously tricky. Brooke Johnson, a paleontologist at the University of Liège in Belgium, has visited Ediacaran outcrops in the U.K. with his colleagues and sometimes struggled to spot the specific fossils he knows are there.

Assessing unfamiliar structures is even more fraught. Researchers constantly second-guess themselves for fear of overinterpreting any given shape or shadow in the stone. The specter of crankhood—of being the kind of researcher who drives their work off a cliff by refusing to be proved wrong—hangs over everybody. “It’s very easy to get yourself tricked into thinking that you can see something that isn’t there, because you’re used to seeing a particular pattern,” Johnson says.

One spring morning in 2023, while working through hundreds of samples of rock more than one billion years old from drill cores from Australia, Johnson knocked over one of the pieces. The rock rolled into a strip of sunlight cutting through the blinds. Johnson abruptly noticed structures picked out by the low-angle light like tiny, quilted chains across the surface of the stone. A careful reexamination of many of the drill cores—rocks many previous geologists had handled without comment—showed the structures were common across the samples.

Johnson speaks cautiously about the structures and has yet to publish his findings on them formally. But he thinks they might be some type of colony-living eukaryote of a size significantly larger than the microscopic examples known from elsewhere in the early fossil record.

The fact that Johnson noticed the structures in the drill core samples only by chance has shaken his initial skepticism of El Albani’s work. “Something like the Francevillian stuff, people might have found it already in other rocks and just not seen it,” he says. “It just might be because they haven’t looked at it in the right way.”

The sheer vanity of forms is why El Albani is surprised that people could look at them and assume they aren’t fossils.

Dealing with material like the Francevillian requires trying to understand a time when Earth looked virtually nothing like the world we know now, Porter says. Much of the history of multicellular life occurred across an abyss of time on what was effectively an alien planet, with environmental conditions that were remarkably different from those of the past 600 million years. These conditions affected life in ways that are still only dimly understood. And the further back in time one goes, the more likely it is that any fossils will be difficult to recognize, to say nothing of categorize.

The temptation for the field to dismiss “fossil-ish” forms as mineral concretions or the product of some other nonbiological process rather than a biogenic one therefore exerts a nearly gravitational pull. “I would imagine they’re probably frustrated [and thinking], ‘Why isn’t everybody already excited about this and coming along with us?’” Riedman says of El Albani and his colleagues. “And we’re just like, ‘We’re stuck on step one, man. We haven’t gotten past the biogenic part.’”

“I don’t know what we need to show to prove, to convince,” El Albani says, his expression hangdog. He’s sitting in his office below a poster of the cover of a June 2024 issue of Science in which he and his team published their discovery of a remarkable trilobite fossil. “There’s no trouble with trilobites,” he remarks wistfully. El Albani is not a bomb thrower by nature and is not in a rush to name names. But a visible exasperation creeps in when he discusses the Gabonese specimens, along with a tendency to simultaneously pick at and try to dismiss the wound.

At the end of the day, it is a question not really of belief but of arguments, El Albani says. If his critics believe the Gabonese specimens are concretions, they need to try to prove that rather than simply asserting it. If they disagree that the rocks contain fossils of eukaryotes, nothing is stopping them from subjecting the specimens to their own analyses. So far he feels that nobody has published any research that takes their conclusions apart point by point and reckons with all the strands of evidence they’ve marshaled. “If I give my opinion that your iPhone is Samsung,” he says, pulling a phone across the desk, “I should explain why!”

Porter, the U.C.S.B. paleontologist, agrees. She’s not convinced by the team’s arguments for what the Francevillian samples represent—an independent lineage of colonial multicellular organisms, swiftly flowering, swiftly snuffed out. But the idea that they’re all just mineral concretions has never satisfied her. If they’re concretions, that’s something researchers need to affirmatively show, she says. Doing so, after all, would add to the field’s knowledge about how pseudofossils form in a way that simply writing them off does not. “We don’t want to discourage people from publishing these weird structures that are difficult to understand,” Porter says.

“It’s fine if they’re wrong,” Porter says of El Albani and his colleagues. Everyone is offering competing hypotheses, which are always subject to new evidence from the fossil record. In the end, “we’ll probably all be somewhat wrong about our interpretation, actually.”

Seventeen years after El Albani first stopped to examine a glinting blob in the Gabonese shale, his lab shows no signs of slowing down. There are always more specimens to publish, avenues of research to pursue, dissertations to finish. Members of the group are working on closer comparisons between the different environments preserved in the Francevillian quarry and the Cambrian deposits, between the chemistry of the Gabonese specimens and fossils from the Ediacaran and the Burgess Shale.

They’re also digging further into the question of how, precisely, chemistry can definitively distinguish between biological and nonbiological origins for a given specimen. Findings from research like theirs could eventually be used to evaluate rock samples from other planets. In 2020 a team of researchers reported that the NASA Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity had photographed millimeter-size, sticklike structures in an ancient lake bed that resembled fossils left by miniature tunnelers on Earth. To date, it’s been impossible to disprove nonbiological explanations for their presence. But if a lab could develop a reliable conceptual model for chemically distinguishing between signs of life and nonlife, “you could apply this on Mars or another planet based on the sediment,” El Albani says.

Every year El Albani and his team make the trip to Gabon to work the scrape of black stone that reoriented his life. There they comb the flaking shales, prying apart slabs, alert to the glimmer of pyrite or the soft, subtle impression of a circular form stamped in the petrified silt. Sometimes El Albani live-streams the expeditions to French schoolchildren, explaining to them how the cellular revolution that gave rise to them lies far back in the mists of prehistory. Sometimes he bends down to examine a glittering form in the rock. It’s probably something. The question, as always, is what.