A Massive Effort Is Underway to Rid the Baltic Sea of Sunken Bombs

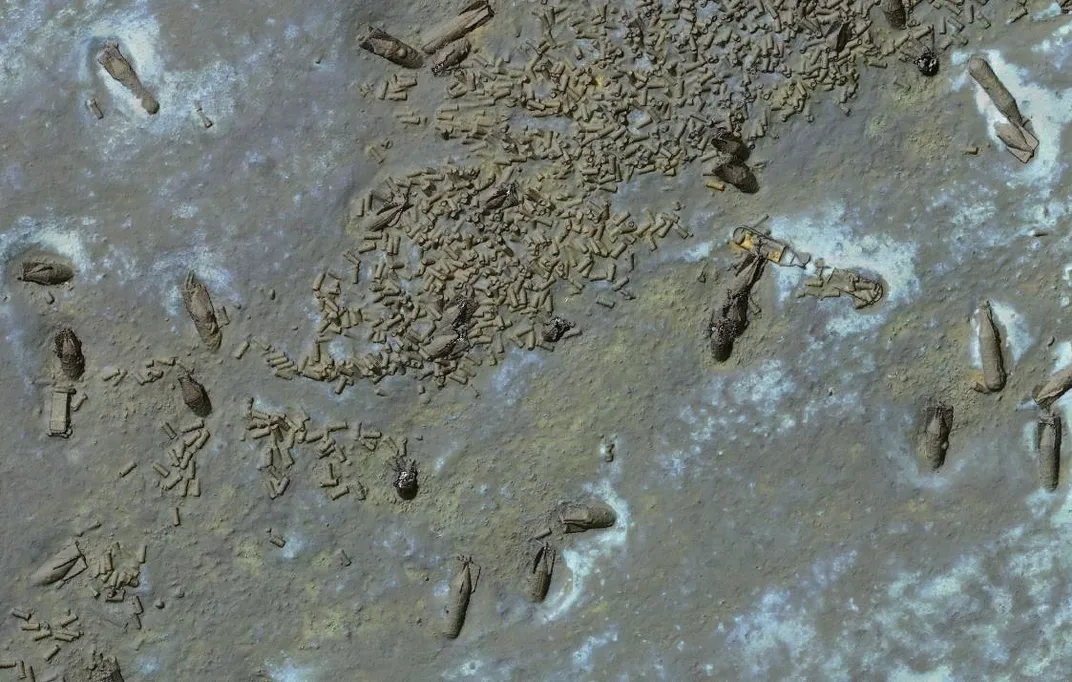

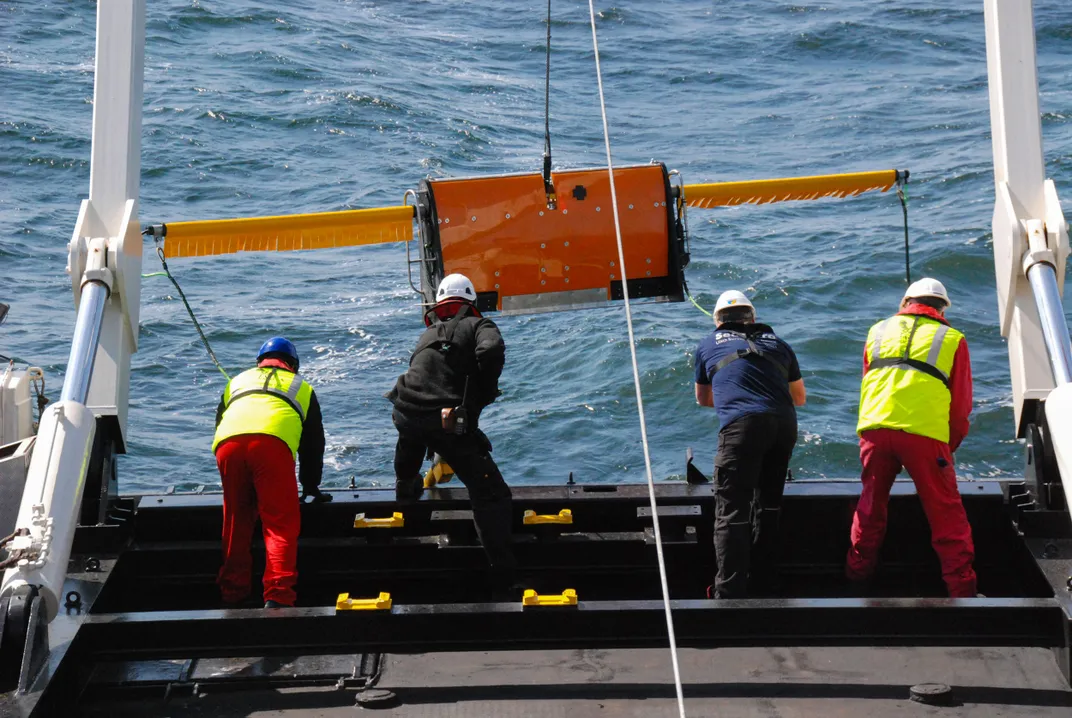

Germany’s North and Baltic Seas are littered with munitions from the First and Second World Wars, such as shells—as shown here—once fired from German battleships. SeaTerra Aboard the Alkor, a 180-foot oceanographic vessel anchored in the Baltic Sea a few miles from the German port city of Kiel, engineer Henrik Schönheit grips a joystick-like lever in his fist. He nudges the lever up, and a one-of-a-kind robotic sea crawler about the size of a two-seat golf cart responds, creeping forward along the seafloor on rubber caterpillar tracks 40 feet below the ship. As the crawler inspects Kiel Bay’s sandy terrain, a live video stream beams up to a computer screen in a cramped room aboard the ship. The picture is so crystalline that it’s possible to count the tentacles of a translucent jellyfish floating past the camera. A scrum of scientists and technicians ooh and aah as they huddle around the screen, peering over Schönheit’s shoulder. The bright-yellow robot is the Norppa 300, the newest fabrication of the explosive ordnance disposal company SeaTerra, which operates out of northern Germany. SeaTerra’s co-founder Dieter Guldin rates as one of Europe’s canniest experts on salvaging sunken explosives. Now, after years of experience clearing the seafloor of hazards for commercial operations, and campaigning the German government for large-scale remediation, SeaTerra is one of three companies participating in the first-ever mission to systematically clear munitions off a seafloor in the name of environmental protection. The arduous and exacting process of removing and destroying more than 1.6 million tons of volatile munitions from the Baltic and North Sea basins—an area roughly the size of West Virginia—is more urgent by the day: The weapons, which have killed hundreds of people who have come into accidental contact with them in the past, are now corroded. Their casings are breaking apart and releasing carcinogens into the seas. Onboard the Alkor, during a test run this May, SeaTerra technicians Klaus-Dieter Golla, left, and Henrik Schönheit discuss video footage of the seafloor transmitted by the company’s Norppa 300 robot. Andreas Muenchbach SeaTerra’s top technicians aboard the Alkor are testing the Norppa 300’s basic functions in the wild prior to the project’s start this month, in early September 2024: ensuring that its steering, sonar imaging of the seafloor, chemical sampler and video feed are fine-tuned. Everyone huddled in the ship’s dry lab watches rapt as the crawler bumps up against a vaguely rectangular object the size of a bar fridge. It’s largely obscured by seaweed and, from the looks of it, home to a lone Baltic flounder that’s swimming around the base. Aaron Beck, senior scientist at the Geomar Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research, a German marine research institute working alongside SeaTerra, identifies it as an ammunition crate. “Look, the flatness there, the corner. That’s not of the natural world,” he exclaims. Dumped munitions lie in waters around the world but are ubiquitous in German waters. In the aftermath of World War II, all the conflict parties, including the United Kingdom, Russia, Japan and the United States, had to divest themselves of armaments. “They didn’t want [them] on land, and facilities to destroy [them] were too few,” explains Anita Künitzer of the German Environment Agency. Dumping at sea, a practice held over from World War I, was the obvious choice. In occupied Germany, British forces established underwater disposal zones—one of which lies near Kiel Bay. “But,” says Guldin, “on their way to the designated dumping grounds, they also just threw hardware overboard.” Grainy black-and-white film footage shows British sailors busily operating multiple conveyor belts to cast crate after crate of leftovers into the sea. Whole ships and submarines packed with live munitions were scuttled in the rush to disarm the Germans. 1500 Miles Of Bombs Along Our Roads Aka Ammunition Dumps Or Arms Dump (1946) Experts estimate that a ginormous 1.8 million tons of conventional munitions and another 5,500 tons of chemical weapons lie decomposing off Germany alone in the North and Baltic Seas, most from World War II. (Because of its busy ports, the North Sea received four times as much as the Baltic.) If all that weaponry were lined up, it would stretch from Paris to Moscow, about 1,500 miles! “Nowhere in German waters is there a square kilometer of seabed without munitions,” says Guldin. In the postwar decades, freelancing scrap metal collectors hauled explosives and other valuable wartime debris ashore to hawk on the metals market. Fisher boats that ensnared unexploded munitions in their nets were required to turn them in to coastal authorities, not toss them overboard again. The German Navy’s anti-mine units attempted to clear some of the mess, usually through initiating underwater explosions, but lacked the proper equipment to tackle the problem systematically. Only when the private sector picked up operations did a whole new suite of technology and skill sets emerge. Since the late 2000s, SeaTerra’s ensemble of marine biologists, hydraulic specialists, sedimentologists, divers, engineers, geophysicists, marine surveyors, pyrotechnicians and archaeologists—now about 160 people—have been mapping the sunken armaments as they worked to clear safe patches of seafloor for wind-farm, cable and pipeline projects. But until this year, SeaTerra never possessed the remit it has long coveted: to begin systematically ameliorating the seafloor for the sake of marine ecosystems—and the people dependent on them. The German government has set aside 100 million euros (over $110 million) to remove the toxic mess from Lübeck Bay, off the Baltic port city of Lübeck, southeast of Kiel, as a pilot project. “No other country in the world has ever attempted or achieved this,” says Tobias Goldschmidt, the region’s environment minister, in a press release. Experts prepare the Norppa 300 for a trial run in the Baltic Sea in May. Andreas Muenchbach Guldin and other advocates are elated that the project is on, but they acknowledge it will only dent the Baltic’s total quantity of submerged ordnance. Their goal is to recover between 55 and 88 tons worth of munitions, though the pilot’s primary purpose is for SeaTerra and the two other firms to test their technology and to demonstrate to bankrollers that the job is doable. “Then it’s about scaling up and getting faster,” says Guldin. Faster is vital, because in their watery graves, the many land and naval mines, U-boat torpedoes, depth charges, artillery shells, chemical weapons, aerial bombs, and incendiary devices have corroded over almost 80 years. The Germans, like other dumping nations, long assumed that when the casings broke down, the vast ocean would simply dissolve pollutants into harmless fractions. About 25 years ago, scientists discovered that instead, the explosives remain live and are now oozing into the ecosystem and up the food chain. That flounder darting in front of the crawler’s camera from the Alkor’s dry lab? It almost certainly contains traces of TNT, the highly toxic compound used in explosives. Toxicologist Jennifer Strehse, from the Kiel-based Institute of Toxicology and Pharmacology for Natural Scientists, which identified the mounting toxic pollution, says that contamination is particularly widespread in shellfish, bottom-dwelling flatfish and other fauna that are close to the munition dumps. They’re “contaminated with carcinogens from TNT or arsenic or heavy metals like lead and mercury,” she says. An image of Lübeck bay’s seafloor shows a smattering of bombs. Geomar Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Scientists have also found toxic concentrations of TNT in Atlantic purple sea urchins, mysid crustaceans and blue mussels. Once contaminants have escaped into the water, they can’t be recovered, Strehse points out. “So, we’re working against time.” German health experts recommend that consumers limit themselves to no more than two meals of local fish a week to reduce exposure to heavy metals, dioxins or PCBs. The source of most of these contaminants are industrial processes and the burning of fossil fuels; TNT does not figure into the guidelines. Nevertheless, the risk of TNT and other contaminants from weapons is enough to cause Strehse, herself, to steer clear of all Baltic Sea mussels. The risk of immediate loss of life is also ever-present. Most of the submerged weapons remain as powerful as the day they were dumped. Now rusted through, they are even more unstable—presenting a precarious obstacle to fishing boats trawling the seafloor as well as offshore wind-farm developers, whose sprawling turbine parks are integral to Europe’s transition to clean energy systems. In the two German seas, over 400 people—tourists, sailors, fishers, naval cadets and munitions experts—have lost their lives to explosions from sunken weapons. German aerial bombs retrieved from the Baltic Sea are stacked and secured before the SeaTerra team transports them ashore for disposal. Germany currently has only one major disposal facility for unexploded ordnance. SeaTerra The menace doesn’t stay at sea, either. As the munitions deteriorate, amber-colored chunks of phosphorous from incendiary bombs, fragments of TNT or rusted casings often wash up on shore. Beachcombers who touch solid white phosphorus—usually mistaking it for Baltic amber, a sought-after gemstone—can suffer third-degree burns or worse. The chemical element sticks to human skin and can combust spontaneously when exposed to air at temperatures above 86 degrees Fahrenheit. Over half a century after the fighting ended, the task of addressing the environmental danger and risk to life from dumped munitions has become its own battle. When Guldin entered the field of munitions cleanup in 2000, he saw the problem’s vastness and malevolent power as the ultimate challenge for his technical imagination. Fifty-seven-year-old Guldin describes himself as a pacifist by nature and archaeologist by training. He grew up far removed from oceans, in southern Germany’s Black Forest where, as a conscientious objector, he refused to serve in the German Army, later joining the Green Party instead. He helped excavate Roman settlements along the Rhine River. Then he moved on to the Middle East, where he unearthed ancient civilizations in Yemen and Lebanon. Eventually, in 2000, he admitted to himself that the long stays abroad and one-off digs weren’t conducive to the family life he wanted. Shortly after this, he touched base with an old friend, Edgar Schwab. Dieter Guldin of SeaTerra has been encouraging the German government to clean up sunken war munitions for years. Drones Magazin Schwab, a geophysicist, was in Hamburg, Germany, and one step ahead of his buddy—starting up a little company to appropriate the lethal relics of the Third Reich from the ocean floor. The two friends were less interested in digging to explain humanity’s past than in undoing the damage it had inflicted upon nature, and together they co-founded SeaTerra. Guldin immersed himself in the history of munitions dumping in Northern Europe—a practice that was discontinued worldwide only in 1975. While SeaTerra conscientiously cleared patches of seafloor for industry, the mass of munitions across the greater seafloor gnawed at him. He insisted that his country clean it up so that future generations wouldn’t suffer this legacy of wars executed by generations past. He worked the halls of power for ten years but couldn’t get officialdom to touch the odious issue. The fact that the seafloor was littered with munitions has been common knowledge since 1945, but no one knew exactly how much there was or where. SeaTerra and a smorgasbord of concerned groups, including Strehse’s institute, understood that before anybody was going to address the issue, they first had to find out exactly what they were dealing with. In the course of its work for private companies, SeaTerra began developing technology—such as a prototype crawler, the DeepC—for surveying the seafloor, foot by excruciating foot. In the deep and churning North Sea, with its muscular tidal currents, much of the detritus lies yards beneath the seafloor. To penetrate the sediment, SeaTerra developed underwater drones and advanced multibeam radar equipment. For shallow tidal areas, SeaTerra also created low-flying drones outfitted with magnetic sensors that can detect metallic masses buried deep in the sand. SeaTerra technicians lower a device called a ScanFish. They use it to tow magnetic sensors through the water, about six feet above the seafloor. SeaTerra Many of SeaTerra’s innovations entailed modifying technology used in related fields, like mining, pyrotechnics and archaeology. The team started with a lot of energy but few resources: “In the beginning, we used zip ties and duct tape for everything,” Guldin says. The range of state-of-the-art technology the team now operates is not the brainchild of one person, but Guldin has been central to much of it. Now, with a firm grasp of the problem and how to address it, Guldin and others at SeaTerra are itching to display their accumulated know-how in Lübeck Bay. “The time has now come,” he announced recently on LinkedIn. “We, the explosive ordnance disposal companies, can now start our real work to make the oceans cleaner … and to measure our ideas and concepts against the physical reality of this blight.” It is, his announcement says, a great success for the company and a “recognition of our many years of effort in developing new technologies and concepts for explosive ordnance at sea.” Aboard the Alkor, the scientists believe their star, the Norppa 300, is ready for official deployment in Lübeck Bay. The crawler is the culmination of years of invention, testing and tweaking. Unlike previous undersea robots, it operates at depths up to almost 1,000 feet and can do so 24/7, even in turbulent waters. Its many functions will relieve professional divers of some of the cleanup expedition’s most perilous tasks. The robot is equipped with sonar and acoustic imaging for detecting and identifying buried munitions. Its detachable arms include a custom-designed vacuum that gingerly sucks up sediment from buried explosives and a pincer for lifting pieces of ammunition. The cleanup process for weapons that can be handled will involve three general steps using specialized ships. First, SeaTerra’s engineers and scientists on the Alkor—the survey vessel—will scan the site and classify the munitions. They will also take water samples for the Geomar Helmholtz Center to analyze on board, distinguishing conventional from chemical weaponry. Chemical weapons, which contain phosgene, arsenic and sulfur mustard (also known as mustard gas), are too lethal to handle, probably ever, admits Guldin. “You can’t see these gases or smell them,” he says, “and their detonation could blow a ship out of the water, killing a ship’s entire crew in a matter of minutes.” Those weapons will be left untouched. Aaron Beck of Geomar Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research stands beside a mass spectrometer, used to analyze the chemical contents of water samples, in the Alkor’s dry lab. Andreas Muenchbach Künitzer of the environment agency adds that the Nazis’ nerve gases were designed to incapacitate the eyes, skin and lungs of battlefield foes. “Decades underwater doesn’t dilute their potency,” she says. If the experts determine the material is safe enough for transportation, they’ll deploy the Norppa 300 to collect and deposit smaller items, like grenades, into undersea wire-mesh baskets. But if the explosive specialists monitoring from the ship above determine that the weaponry still contains detonators, divers—not a robot—will be sent to detach them. This is hazardous business that, thus far, only humans can execute. Next, a different team on a second ship—the clearance vessel—equipped with spud legs (stakes that hold the ship in place) will use a hydraulic crane equipped with cameras to extract larger munitions, including those with corrupted casings, and drop them into undersea receptacles. The final step is for a third team to haul the cargo onto the deck of their ship—the sorting vessel—to sort, label and package the lethal concoctions in steel tubes, and then transport them to an interim site in the Baltic Sea. There the material will be re-sunk in the tubes and stored underwater until it can be handed over to the responsible state authority, the Explosive Ordnance Disposal Service, for demolition. Some of the munitions SeaTerra clears from Germany’s seas date back to World War I, such as the six-inch-long cast iron shell shown here. SeaTerra The workers will have two months to clear the bay—and demonstrate whether the Norppa 300 and other technologies are either up to it or not. But there’s a hitch that will delay the destruction of all of the recovered weapons for about a year. Germany has a single major munitions disposal facility, and it is occupied with incinerating unexploded ordnance from around the globe, not least, incredibly, Nazi-era explosives still being unearthed from construction sites. That’s why the Lübeck Bay project’s budget includes construction of a disposal facility. The company and concept have yet to be finalized. One option is to build a floating clearance platform where robots would dissect ordnance and burn the chemical contents in a detonation chamber at temperatures of over 2300 degrees Fahrenheit, similar to how weapons are disposed of at the land-based facility. And there’s another issue. Over the years, the mounds of weaponry in the undersea dumping grounds have corroded and collapsed into one another, creating a gnarled, combustible mass of metals and explosive agents that make their recovery more complicated. The only options are to leave these or blow them up on-site. The best-case scenario is that all the Baltic’s most hazardous conventional munitions will finally be history by 2050, and work on the North Sea will be well underway. The worst case is that funding does not materialize and the mountains of explosives will continue to deteriorate en masse, emitting poisons. Before the green light came to start the cleanup, Guldin was becoming doubtful his country would ever address the mess, and he thought he might have to accept that SeaTerra’s expertise would never be put to the greater task that he and Schwab had envisioned. For the foreseeable future at least, he’ll be in the thick of culminating his life’s work, undoing some of humanity’s sins on the seafloor. This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com. Related stories from Hakai Magazine: • Weapons of War Litter the Ocean Floor • Why Ocean Shores Beachcombing Is a Blast Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

The ocean became a dumping ground for weapons after Allied forces defeated the Nazis. Now a team of robots and divers is making the waters safer

Aboard the Alkor, a 180-foot oceanographic vessel anchored in the Baltic Sea a few miles from the German port city of Kiel, engineer Henrik Schönheit grips a joystick-like lever in his fist. He nudges the lever up, and a one-of-a-kind robotic sea crawler about the size of a two-seat golf cart responds, creeping forward along the seafloor on rubber caterpillar tracks 40 feet below the ship. As the crawler inspects Kiel Bay’s sandy terrain, a live video stream beams up to a computer screen in a cramped room aboard the ship. The picture is so crystalline that it’s possible to count the tentacles of a translucent jellyfish floating past the camera. A scrum of scientists and technicians ooh and aah as they huddle around the screen, peering over Schönheit’s shoulder.

The bright-yellow robot is the Norppa 300, the newest fabrication of the explosive ordnance disposal company SeaTerra, which operates out of northern Germany. SeaTerra’s co-founder Dieter Guldin rates as one of Europe’s canniest experts on salvaging sunken explosives. Now, after years of experience clearing the seafloor of hazards for commercial operations, and campaigning the German government for large-scale remediation, SeaTerra is one of three companies participating in the first-ever mission to systematically clear munitions off a seafloor in the name of environmental protection. The arduous and exacting process of removing and destroying more than 1.6 million tons of volatile munitions from the Baltic and North Sea basins—an area roughly the size of West Virginia—is more urgent by the day: The weapons, which have killed hundreds of people who have come into accidental contact with them in the past, are now corroded. Their casings are breaking apart and releasing carcinogens into the seas.

SeaTerra’s top technicians aboard the Alkor are testing the Norppa 300’s basic functions in the wild prior to the project’s start this month, in early September 2024: ensuring that its steering, sonar imaging of the seafloor, chemical sampler and video feed are fine-tuned. Everyone huddled in the ship’s dry lab watches rapt as the crawler bumps up against a vaguely rectangular object the size of a bar fridge. It’s largely obscured by seaweed and, from the looks of it, home to a lone Baltic flounder that’s swimming around the base. Aaron Beck, senior scientist at the Geomar Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research, a German marine research institute working alongside SeaTerra, identifies it as an ammunition crate. “Look, the flatness there, the corner. That’s not of the natural world,” he exclaims.

Dumped munitions lie in waters around the world but are ubiquitous in German waters. In the aftermath of World War II, all the conflict parties, including the United Kingdom, Russia, Japan and the United States, had to divest themselves of armaments. “They didn’t want [them] on land, and facilities to destroy [them] were too few,” explains Anita Künitzer of the German Environment Agency. Dumping at sea, a practice held over from World War I, was the obvious choice.

In occupied Germany, British forces established underwater disposal zones—one of which lies near Kiel Bay. “But,” says Guldin, “on their way to the designated dumping grounds, they also just threw hardware overboard.” Grainy black-and-white film footage shows British sailors busily operating multiple conveyor belts to cast crate after crate of leftovers into the sea. Whole ships and submarines packed with live munitions were scuttled in the rush to disarm the Germans.

1500 Miles Of Bombs Along Our Roads Aka Ammunition Dumps Or Arms Dump (1946)

Experts estimate that a ginormous 1.8 million tons of conventional munitions and another 5,500 tons of chemical weapons lie decomposing off Germany alone in the North and Baltic Seas, most from World War II. (Because of its busy ports, the North Sea received four times as much as the Baltic.) If all that weaponry were lined up, it would stretch from Paris to Moscow, about 1,500 miles! “Nowhere in German waters is there a square kilometer of seabed without munitions,” says Guldin.

In the postwar decades, freelancing scrap metal collectors hauled explosives and other valuable wartime debris ashore to hawk on the metals market. Fisher boats that ensnared unexploded munitions in their nets were required to turn them in to coastal authorities, not toss them overboard again. The German Navy’s anti-mine units attempted to clear some of the mess, usually through initiating underwater explosions, but lacked the proper equipment to tackle the problem systematically. Only when the private sector picked up operations did a whole new suite of technology and skill sets emerge.

Since the late 2000s, SeaTerra’s ensemble of marine biologists, hydraulic specialists, sedimentologists, divers, engineers, geophysicists, marine surveyors, pyrotechnicians and archaeologists—now about 160 people—have been mapping the sunken armaments as they worked to clear safe patches of seafloor for wind-farm, cable and pipeline projects.

But until this year, SeaTerra never possessed the remit it has long coveted: to begin systematically ameliorating the seafloor for the sake of marine ecosystems—and the people dependent on them. The German government has set aside 100 million euros (over $110 million) to remove the toxic mess from Lübeck Bay, off the Baltic port city of Lübeck, southeast of Kiel, as a pilot project. “No other country in the world has ever attempted or achieved this,” says Tobias Goldschmidt, the region’s environment minister, in a press release.

Guldin and other advocates are elated that the project is on, but they acknowledge it will only dent the Baltic’s total quantity of submerged ordnance. Their goal is to recover between 55 and 88 tons worth of munitions, though the pilot’s primary purpose is for SeaTerra and the two other firms to test their technology and to demonstrate to bankrollers that the job is doable. “Then it’s about scaling up and getting faster,” says Guldin.

Faster is vital, because in their watery graves, the many land and naval mines, U-boat torpedoes, depth charges, artillery shells, chemical weapons, aerial bombs, and incendiary devices have corroded over almost 80 years. The Germans, like other dumping nations, long assumed that when the casings broke down, the vast ocean would simply dissolve pollutants into harmless fractions. About 25 years ago, scientists discovered that instead, the explosives remain live and are now oozing into the ecosystem and up the food chain.

That flounder darting in front of the crawler’s camera from the Alkor’s dry lab? It almost certainly contains traces of TNT, the highly toxic compound used in explosives. Toxicologist Jennifer Strehse, from the Kiel-based Institute of Toxicology and Pharmacology for Natural Scientists, which identified the mounting toxic pollution, says that contamination is particularly widespread in shellfish, bottom-dwelling flatfish and other fauna that are close to the munition dumps. They’re “contaminated with carcinogens from TNT or arsenic or heavy metals like lead and mercury,” she says.

Scientists have also found toxic concentrations of TNT in Atlantic purple sea urchins, mysid crustaceans and blue mussels. Once contaminants have escaped into the water, they can’t be recovered, Strehse points out. “So, we’re working against time.”

German health experts recommend that consumers limit themselves to no more than two meals of local fish a week to reduce exposure to heavy metals, dioxins or PCBs. The source of most of these contaminants are industrial processes and the burning of fossil fuels; TNT does not figure into the guidelines. Nevertheless, the risk of TNT and other contaminants from weapons is enough to cause Strehse, herself, to steer clear of all Baltic Sea mussels.

The risk of immediate loss of life is also ever-present. Most of the submerged weapons remain as powerful as the day they were dumped. Now rusted through, they are even more unstable—presenting a precarious obstacle to fishing boats trawling the seafloor as well as offshore wind-farm developers, whose sprawling turbine parks are integral to Europe’s transition to clean energy systems. In the two German seas, over 400 people—tourists, sailors, fishers, naval cadets and munitions experts—have lost their lives to explosions from sunken weapons.

The menace doesn’t stay at sea, either. As the munitions deteriorate, amber-colored chunks of phosphorous from incendiary bombs, fragments of TNT or rusted casings often wash up on shore. Beachcombers who touch solid white phosphorus—usually mistaking it for Baltic amber, a sought-after gemstone—can suffer third-degree burns or worse. The chemical element sticks to human skin and can combust spontaneously when exposed to air at temperatures above 86 degrees Fahrenheit.

Over half a century after the fighting ended, the task of addressing the environmental danger and risk to life from dumped munitions has become its own battle. When Guldin entered the field of munitions cleanup in 2000, he saw the problem’s vastness and malevolent power as the ultimate challenge for his technical imagination.

Fifty-seven-year-old Guldin describes himself as a pacifist by nature and archaeologist by training. He grew up far removed from oceans, in southern Germany’s Black Forest where, as a conscientious objector, he refused to serve in the German Army, later joining the Green Party instead. He helped excavate Roman settlements along the Rhine River. Then he moved on to the Middle East, where he unearthed ancient civilizations in Yemen and Lebanon. Eventually, in 2000, he admitted to himself that the long stays abroad and one-off digs weren’t conducive to the family life he wanted. Shortly after this, he touched base with an old friend, Edgar Schwab.

Schwab, a geophysicist, was in Hamburg, Germany, and one step ahead of his buddy—starting up a little company to appropriate the lethal relics of the Third Reich from the ocean floor. The two friends were less interested in digging to explain humanity’s past than in undoing the damage it had inflicted upon nature, and together they co-founded SeaTerra.

Guldin immersed himself in the history of munitions dumping in Northern Europe—a practice that was discontinued worldwide only in 1975. While SeaTerra conscientiously cleared patches of seafloor for industry, the mass of munitions across the greater seafloor gnawed at him. He insisted that his country clean it up so that future generations wouldn’t suffer this legacy of wars executed by generations past. He worked the halls of power for ten years but couldn’t get officialdom to touch the odious issue.

The fact that the seafloor was littered with munitions has been common knowledge since 1945, but no one knew exactly how much there was or where. SeaTerra and a smorgasbord of concerned groups, including Strehse’s institute, understood that before anybody was going to address the issue, they first had to find out exactly what they were dealing with.

In the course of its work for private companies, SeaTerra began developing technology—such as a prototype crawler, the DeepC—for surveying the seafloor, foot by excruciating foot. In the deep and churning North Sea, with its muscular tidal currents, much of the detritus lies yards beneath the seafloor. To penetrate the sediment, SeaTerra developed underwater drones and advanced multibeam radar equipment. For shallow tidal areas, SeaTerra also created low-flying drones outfitted with magnetic sensors that can detect metallic masses buried deep in the sand.

Many of SeaTerra’s innovations entailed modifying technology used in related fields, like mining, pyrotechnics and archaeology. The team started with a lot of energy but few resources: “In the beginning, we used zip ties and duct tape for everything,” Guldin says. The range of state-of-the-art technology the team now operates is not the brainchild of one person, but Guldin has been central to much of it.

Now, with a firm grasp of the problem and how to address it, Guldin and others at SeaTerra are itching to display their accumulated know-how in Lübeck Bay. “The time has now come,” he announced recently on LinkedIn. “We, the explosive ordnance disposal companies, can now start our real work to make the oceans cleaner … and to measure our ideas and concepts against the physical reality of this blight.” It is, his announcement says, a great success for the company and a “recognition of our many years of effort in developing new technologies and concepts for explosive ordnance at sea.”

Aboard the Alkor, the scientists believe their star, the Norppa 300, is ready for official deployment in Lübeck Bay. The crawler is the culmination of years of invention, testing and tweaking. Unlike previous undersea robots, it operates at depths up to almost 1,000 feet and can do so 24/7, even in turbulent waters. Its many functions will relieve professional divers of some of the cleanup expedition’s most perilous tasks. The robot is equipped with sonar and acoustic imaging for detecting and identifying buried munitions. Its detachable arms include a custom-designed vacuum that gingerly sucks up sediment from buried explosives and a pincer for lifting pieces of ammunition.

The cleanup process for weapons that can be handled will involve three general steps using specialized ships. First, SeaTerra’s engineers and scientists on the Alkor—the survey vessel—will scan the site and classify the munitions. They will also take water samples for the Geomar Helmholtz Center to analyze on board, distinguishing conventional from chemical weaponry. Chemical weapons, which contain phosgene, arsenic and sulfur mustard (also known as mustard gas), are too lethal to handle, probably ever, admits Guldin. “You can’t see these gases or smell them,” he says, “and their detonation could blow a ship out of the water, killing a ship’s entire crew in a matter of minutes.” Those weapons will be left untouched.

Künitzer of the environment agency adds that the Nazis’ nerve gases were designed to incapacitate the eyes, skin and lungs of battlefield foes. “Decades underwater doesn’t dilute their potency,” she says.

If the experts determine the material is safe enough for transportation, they’ll deploy the Norppa 300 to collect and deposit smaller items, like grenades, into undersea wire-mesh baskets. But if the explosive specialists monitoring from the ship above determine that the weaponry still contains detonators, divers—not a robot—will be sent to detach them. This is hazardous business that, thus far, only humans can execute.

Next, a different team on a second ship—the clearance vessel—equipped with spud legs (stakes that hold the ship in place) will use a hydraulic crane equipped with cameras to extract larger munitions, including those with corrupted casings, and drop them into undersea receptacles. The final step is for a third team to haul the cargo onto the deck of their ship—the sorting vessel—to sort, label and package the lethal concoctions in steel tubes, and then transport them to an interim site in the Baltic Sea. There the material will be re-sunk in the tubes and stored underwater until it can be handed over to the responsible state authority, the Explosive Ordnance Disposal Service, for demolition.

The workers will have two months to clear the bay—and demonstrate whether the Norppa 300 and other technologies are either up to it or not.

But there’s a hitch that will delay the destruction of all of the recovered weapons for about a year. Germany has a single major munitions disposal facility, and it is occupied with incinerating unexploded ordnance from around the globe, not least, incredibly, Nazi-era explosives still being unearthed from construction sites. That’s why the Lübeck Bay project’s budget includes construction of a disposal facility. The company and concept have yet to be finalized. One option is to build a floating clearance platform where robots would dissect ordnance and burn the chemical contents in a detonation chamber at temperatures of over 2300 degrees Fahrenheit, similar to how weapons are disposed of at the land-based facility.

And there’s another issue. Over the years, the mounds of weaponry in the undersea dumping grounds have corroded and collapsed into one another, creating a gnarled, combustible mass of metals and explosive agents that make their recovery more complicated. The only options are to leave these or blow them up on-site. The best-case scenario is that all the Baltic’s most hazardous conventional munitions will finally be history by 2050, and work on the North Sea will be well underway. The worst case is that funding does not materialize and the mountains of explosives will continue to deteriorate en masse, emitting poisons.

Before the green light came to start the cleanup, Guldin was becoming doubtful his country would ever address the mess, and he thought he might have to accept that SeaTerra’s expertise would never be put to the greater task that he and Schwab had envisioned. For the foreseeable future at least, he’ll be in the thick of culminating his life’s work, undoing some of humanity’s sins on the seafloor.

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Related stories from Hakai Magazine:

• Weapons of War Litter the Ocean Floor

• Why Ocean Shores Beachcombing Is a Blast

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.