A Land Back Success for the Amah Mutsun Within Its Historical Territory

Later this year, the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band—Indigenous people whose ancestors lived throughout the river valleys that stretch inland from Monterey Bay—will reclaim land within the tribe’s historical territory for the first time in more than two centuries. The tribe’s land trust will acquire 50-acres in the Gabilan foothills, near the confluence of the San Benito and Pajaro rivers, south of State Route 129 in San Benito County. Sloping gently from oak woodlands to the grassland valley below, the site lies in the southern reaches of Juristac, a region of the Amah Mutsun’s ancestral territory that encompasses up to 100 square miles, and contains many areas and objects considered sacred by the tribe. (Courtesy of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust)“The property is within the greater Juristac landscape, which is a very sacred site,” said tribal chairman Valentin Lopez, who serves as president of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust. Lopez said the parcel will be preserved as open space where tribal members can practice land stewardship, such as native plant restoration, while maintaining the wildlife connectivity of the area. “It’s our responsibility to take care of Mother Earth and all living things,” he said. “So taking care of this area as a wildlife corridor is right in line with our cultural values and our directive from Creator.” The 50-acre parcel is one of several properties the California tribe is working to acquire, or gain access rights to, after multiple waves of colonization since the 18th century left them without a land base. In the early 2000s, Amah Mutsun leaders organized efforts to restore the connections their ancestors had to their lands and culture prior to the Mission era. The Amah Mutsun Land Trust was established a decade ago to spearhead that work, and, in the time since, the nonprofit has expanded its land-stewardship programs while securing agreements for several cultural easements within the tribe’s traditional territory. The organization’s efforts culminated in the recent land transfer, in which the Community Foundation Santa Cruz County donated the 50-acre property to the Amah Mutsun Land Trust. While the land trust owns a two-acre property in Bonny Dune—within the historical territory of Awaswas-speaking people, whose villages were concentrated in the north Monterey Bay-area—the transfer marks the Amah Mutsun’s first land acquisition within its traditional territory since the 1790s, when Spanish missionaries forcibly relocated the area’s Indigenous people to Mission San Juan Bautista. The property will be transferred from the Community Foundation Santa Cruz County to the Amah Mutsun Land Trust this fall. (Ben Pease, PeasePress.com)A committee of tribal members named the place tooromakma hinse nii (pronounced toe row mock ma hēēn say knee), which, in the Mutsun language, means “bobcats wander here.” Along with lodging for Lynx rufus, the area known as Chittenden Pass serves as a critical wildlife corridor for mountain lions, American badger and California tiger salamander. Lopez said the land will provide members of the Native Stewardship Corps, a program of the land trust’s, an opportunity to perform conservation and native plant propagation work on their own lands, affording the young adults a greater level of cultural engagement. Before COVID-19 spurred a five-year hiatus, the Native stewards were performing work akin to a conventional conservation corps, Lopez said. “The purpose was also to restore relationships with the plants and the wildlife, and to take the time to show reciprocity in their work,” Lopez said. “There was a strong learning and cultural component for our stewards that wasn’t happening; they were just turning into a workforce.” The land was previously purchased by the Community Foundation Santa Cruz County in collaboration with the Trust for Public Land, Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, and Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) with the intent of eventually transferring the property to the Amah Mutsun Land Trust. “This moment is transformational,” said Noelle Chambers, who was named as AMLT’s executive director in April. “The first decade of the organization was focused on building partnerships while re-learning and re-engaging Indigenous stewardship practices. After building our organizational capacity, we are positioned to move into the next phase of AMLT – acquiring lands for long-term Tribal stewardship.” Before taking her leadership role with the Amah Mutsun Land Trust, Chambers served as vice president of conservation for POST. Her work with the organization included collaborating with Chairman Lopez and AMLT on various conservation efforts in the area, she said, adding that it has been important for her as a non-Native person to learn about Indigenous perspectives on land stewardship and how to better integrate those practices in the conservation field. “It’s very exciting to have the ability to help the Amah Mutsun Land Trust acquire their first lands,” Chambers said. “It felt like a natural next step to use the skills I learned in my years at POST to work toward the return of land to the Mutsun people, and stewarding lands with Indigenous practices.” Chambers said the land trust is also exploring an opportunity to acquire a third property—almost 30-acres near Chitactac, the site of a Mutsun village west of present-day Gilroy. Situated close to Chitactac–Adams Heritage County Park, the property is bisected by a road and contains dozens of bedrock mortars used by Mutsun people to grind acorns and other foods.The organization is applying for grant funding to buy the land from the current landowner, she said. Bordered by Uvas Creek, the parcel currently holds agricultural fields that could one day be used to propagate native plants, Lopez said. (Along with the tribe’s planned restoration efforts at the San Benito Valley property, the tribe intends to create a native plant garden on a conservation easement atop Mt. Umunhum, a peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains.) “Chitactac translates to ‘the place of the dance,’” Lopez said. “This was a very important ceremonial landscape and an extensive village site.” Gaining access rights to the Chitactac property would be another notable accomplishment for the California tribe, which was never provided a federal Indian reservation and is still seeking federal recognition. From left: Christy Fischer (Trust for Public Land), Valentin Lopez (Tribal Chair and AMLT Board President), Susan True (Community Foundation Santa Cruz County), and Athena Hernandez (Tribal member and former AMLT General Counsel) (Courtesy of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust)Despite the significant steps the Amah Mutsun have made toward legal land-ownership in the settler-colonial sense, Lopez said the land trust’s limited financial resources make large real estate acquisitions nearly impossible without support from larger conservation groups. One such organization is POST, which over the past year purchased two properties totaling 3,800 acres of rolling, open oak woodlands within the Juristac area. Located on the Sargent Ranch property west of Highway 101, the parcels were previously owned by the developer of a proposed sand-and-gravel mine that would operate on the remaining portion of the property. Bay Nature previously reported on Lopez and other tribal members’ vehement opposition to the quarry project, saying it would desecrate an area where Mutsun people once gathered for large ceremonies. Three years after the release of a preliminary EIR that drew thousands of public comments opposing the plan, the quarry proposal is currently on hold. It is unclear whether the project will move forward. Howard Justus, managing member of Sargent Ranch Partners, the San Diego-based company behind the project, declined to comment on the status of the proposal. Whatever the fate of the quarry, POST has signaled that the Sargent Ranch properties will be preserved in perpetuity, partly to maintain a crucial wildlife corridor at the foot of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The first purchase took place in October 2024, when the organization bought 1,340 acres for $15.65 million from an investor group that acquired the parcel in 2020. In a press release following the sale, POST stated that it would “retain ownership of the property until it can be transferred to a permanent steward.” In June, the environmental group purchased nearly 2,500 acres from Sargent Ranch Partners for a reported sum of $25 million. Neither POST nor AMLT disclosed any plans for a potential future land transfer at Sargent Ranch, though both have expressed a willingness to collaborate on future conservation efforts. But, now that nearly two-thirds of Sargent Ranch are owned by a conservation organization, Chambers acknowledged that POST’s purchases represent “a huge step” from AMLT’s perspective, adding “we’re really hoping POST is able to secure the rest of it.” Lopez said he is “very grateful” that the two properties will no longer be threatened by the development of luxury housing or golf courses. “We have a good relationship with POST,” he said. “So we’re hoping that we can find a way to have access and do some stewardship up there.” On the prospect of the Amah Mutsun someday owning some significant portion of Sargent Ranch, Lopez said “it would take a miracle” given the tribe’s limited resources. “Our prayers and our efforts aren’t for ownership,” he said. “Our prayers are for the protection of the land, and for the opportunity to restore it back to the important spiritual location that it was during our ancestors’ time.”

The tribe has been landless for more than 200 years. The post A Land Back Success for the Amah Mutsun Within Its Historical Territory appeared first on Bay Nature.

Later this year, the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band—Indigenous people whose ancestors lived throughout the river valleys that stretch inland from Monterey Bay—will reclaim land within the tribe’s historical territory for the first time in more than two centuries.

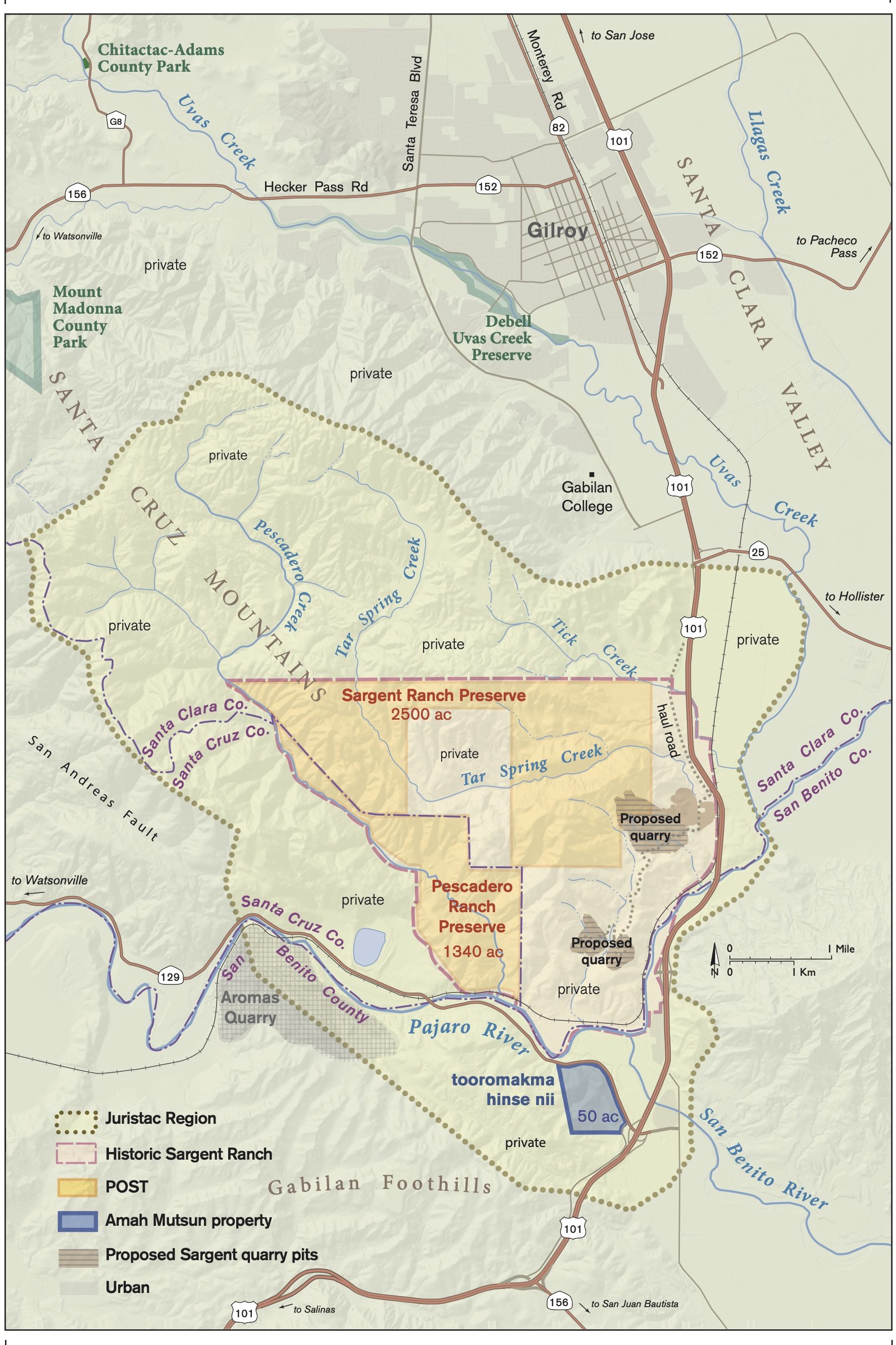

The tribe’s land trust will acquire 50-acres in the Gabilan foothills, near the confluence of the San Benito and Pajaro rivers, south of State Route 129 in San Benito County. Sloping gently from oak woodlands to the grassland valley below, the site lies in the southern reaches of Juristac, a region of the Amah Mutsun’s ancestral territory that encompasses up to 100 square miles, and contains many areas and objects considered sacred by the tribe.

“The property is within the greater Juristac landscape, which is a very sacred site,” said tribal chairman Valentin Lopez, who serves as president of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust. Lopez said the parcel will be preserved as open space where tribal members can practice land stewardship, such as native plant restoration, while maintaining the wildlife connectivity of the area.

“It’s our responsibility to take care of Mother Earth and all living things,” he said. “So taking care of this area as a wildlife corridor is right in line with our cultural values and our directive from Creator.”

The 50-acre parcel is one of several properties the California tribe is working to acquire, or gain access rights to, after multiple waves of colonization since the 18th century left them without a land base. In the early 2000s, Amah Mutsun leaders organized efforts to restore the connections their ancestors had to their lands and culture prior to the Mission era. The Amah Mutsun Land Trust was established a decade ago to spearhead that work, and, in the time since, the nonprofit has expanded its land-stewardship programs while securing agreements for several cultural easements within the tribe’s traditional territory.

The organization’s efforts culminated in the recent land transfer, in which the Community Foundation Santa Cruz County donated the 50-acre property to the Amah Mutsun Land Trust. While the land trust owns a two-acre property in Bonny Dune—within the historical territory of Awaswas-speaking people, whose villages were concentrated in the north Monterey Bay-area—the transfer marks the Amah Mutsun’s first land acquisition within its traditional territory since the 1790s, when Spanish missionaries forcibly relocated the area’s Indigenous people to Mission San Juan Bautista.

A committee of tribal members named the place tooromakma hinse nii (pronounced toe row mock ma hēēn say knee), which, in the Mutsun language, means “bobcats wander here.” Along with lodging for Lynx rufus, the area known as Chittenden Pass serves as a critical wildlife corridor for mountain lions, American badger and California tiger salamander.

Lopez said the land will provide members of the Native Stewardship Corps, a program of the land trust’s, an opportunity to perform conservation and native plant propagation work on their own lands, affording the young adults a greater level of cultural engagement. Before COVID-19 spurred a five-year hiatus, the Native stewards were performing work akin to a conventional conservation corps, Lopez said.

“The purpose was also to restore relationships with the plants and the wildlife, and to take the time to show reciprocity in their work,” Lopez said. “There was a strong learning and cultural component for our stewards that wasn’t happening; they were just turning into a workforce.”

The land was previously purchased by the Community Foundation Santa Cruz County in collaboration with the Trust for Public Land, Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, and Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) with the intent of eventually transferring the property to the Amah Mutsun Land Trust.

“This moment is transformational,” said Noelle Chambers, who was named as AMLT’s executive director in April. “The first decade of the organization was focused on building partnerships while re-learning and re-engaging Indigenous stewardship practices. After building our organizational capacity, we are positioned to move into the next phase of AMLT – acquiring lands for long-term Tribal stewardship.”

Before taking her leadership role with the Amah Mutsun Land Trust, Chambers served as vice president of conservation for POST. Her work with the organization included collaborating with Chairman Lopez and AMLT on various conservation efforts in the area, she said, adding that it has been important for her as a non-Native person to learn about Indigenous perspectives on land stewardship and how to better integrate those practices in the conservation field.

“It’s very exciting to have the ability to help the Amah Mutsun Land Trust acquire their first lands,” Chambers said. “It felt like a natural next step to use the skills I learned in my years at POST to work toward the return of land to the Mutsun people, and stewarding lands with Indigenous practices.”

Chambers said the land trust is also exploring an opportunity to acquire a third property—almost 30-acres near Chitactac, the site of a Mutsun village west of present-day Gilroy. Situated close to Chitactac–Adams Heritage County Park, the property is bisected by a road and contains dozens of bedrock mortars used by Mutsun people to grind acorns and other foods.The organization is applying for grant funding to buy the land from the current landowner, she said. Bordered by Uvas Creek, the parcel currently holds agricultural fields that could one day be used to propagate native plants, Lopez said. (Along with the tribe’s planned restoration efforts at the San Benito Valley property, the tribe intends to create a native plant garden on a conservation easement atop Mt. Umunhum, a peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains.)

“Chitactac translates to ‘the place of the dance,’” Lopez said. “This was a very important ceremonial landscape and an extensive village site.”

Gaining access rights to the Chitactac property would be another notable accomplishment for the California tribe, which was never provided a federal Indian reservation and is still seeking federal recognition.

Despite the significant steps the Amah Mutsun have made toward legal land-ownership in the settler-colonial sense, Lopez said the land trust’s limited financial resources make large real estate acquisitions nearly impossible without support from larger conservation groups.

One such organization is POST, which over the past year purchased two properties totaling 3,800 acres of rolling, open oak woodlands within the Juristac area. Located on the Sargent Ranch property west of Highway 101, the parcels were previously owned by the developer of a proposed sand-and-gravel mine that would operate on the remaining portion of the property. Bay Nature previously reported on Lopez and other tribal members’ vehement opposition to the quarry project, saying it would desecrate an area where Mutsun people once gathered for large ceremonies. Three years after the release of a preliminary EIR that drew thousands of public comments opposing the plan, the quarry proposal is currently on hold. It is unclear whether the project will move forward. Howard Justus, managing member of Sargent Ranch Partners, the San Diego-based company behind the project, declined to comment on the status of the proposal.

Whatever the fate of the quarry, POST has signaled that the Sargent Ranch properties will be preserved in perpetuity, partly to maintain a crucial wildlife corridor at the foot of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The first purchase took place in October 2024, when the organization bought 1,340 acres for $15.65 million from an investor group that acquired the parcel in 2020. In a press release following the sale, POST stated that it would “retain ownership of the property until it can be transferred to a permanent steward.” In June, the environmental group purchased nearly 2,500 acres from Sargent Ranch Partners for a reported sum of $25 million.

Neither POST nor AMLT disclosed any plans for a potential future land transfer at Sargent Ranch, though both have expressed a willingness to collaborate on future conservation efforts. But, now that nearly two-thirds of Sargent Ranch are owned by a conservation organization, Chambers acknowledged that POST’s purchases represent “a huge step” from AMLT’s perspective, adding “we’re really hoping POST is able to secure the rest of it.”

Lopez said he is “very grateful” that the two properties will no longer be threatened by the development of luxury housing or golf courses. “We have a good relationship with POST,” he said. “So we’re hoping that we can find a way to have access and do some stewardship up there.” On the prospect of the Amah Mutsun someday owning some significant portion of Sargent Ranch, Lopez said “it would take a miracle” given the tribe’s limited resources.

“Our prayers and our efforts aren’t for ownership,” he said. “Our prayers are for the protection of the land, and for the opportunity to restore it back to the important spiritual location that it was during our ancestors’ time.”